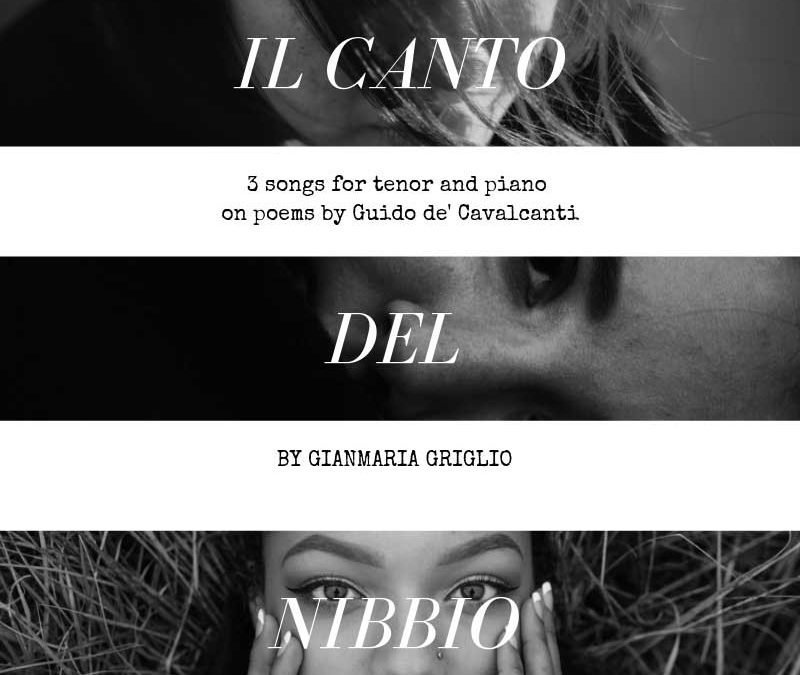

Il canto nibbio

I started writing these 3 pieces on a whim: looking for inspiration in poetry, I stumbled upon an old book of

Cavalcanti lived in the 13th century, which obviously makes his Italian very different from the one we speak nowadays. This, in turn, made it for a nice challenge. Now, while I was reading through various poems, Bill Evans was playing his glorious album with Chet Baker. I love Evans’ music, and it occurred to me that his troubled life was not that different from Cavalcanti’s, some 600 years earlier. They both pursued a philosophical exploration of love, though in different forms, while never been able to reach peace till the end.

Cavalcanti died of malaria while trying to return from an exile imposed by the never-ending war between Guelphs (supporters of the pope) and Ghibellines (supporters of the Holy Roman Empire); Evans died from a never-ending battle with himself, which eventually led to a combination of untreated hepatitis, cirrhosis and pneumonia.

The second romanza of this cycle is dedicated to Bill Evans and makes large use of his harmonic language combined with my Italian heritage.

Guido de' Cavalcanti

Guido was born in Florence at a time when the city was beginning its economic, political, intellectual and artistic ascendancy as one of the leading cities of the Renaissance. The son of Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti – a guelph that Dante puts in the sixth ring of his Inferno – Guido, along with Dante himself, was a part of the Tuscan poetic movement known as the Dolce stil novo (Sweet New Style).

The Stilnovismo brought an originality to and completely transformed the poetry of courtly love exploring the philosophical, spiritual, psychological and social effects of love through a poetry that championed the Tuscan vernacular, thus influencing generations of poets to come.

Cavalcanti’s controversial personality and beliefs attracted the attention of Boccaccio, who made him part of his Decameron. Cavalcanti’s poetry was admired later on by Ezra Pound and T.S.Eliot, who used an adaptation of the opening line of Perch’i’ no spero di tornar giammai (“Because I do not hope to turn again”) to open his 1930 poem Ash Wednesday.

Bill Evans

Bill Evans was born in 1929 in North Plainfield, New Jersey: his parents’ marriage was stormy, thanks to his father’s heavy drinking, gambling, and abuse. Bill had a brother, Harry, two years older, with whom he shared a very close relationship.

Bill’s father habits forced Mary Evans to often leave home with her sons, to stay with her sister in the nearby town of Somerville where Bill got his first piano lessons.

Later he received also violin and flute lessons, instruments that he eventually dropped. The influences of classical music were fundamental in Evans development: from Stravinsky to Milhaud, from Mozart to Debussy.

The impressionist period left a particular mark on his style: there are chords changes in Ravel’s Le tombeau de Couperin that would be later evoked very clearly by Evans; the subtle voicing of the jazz giant goes back to Debussy. Nothing is for the sake of show-off: every note has a purpose, and his style and playing still influence generations of pianists.

Voi che per gli occhi

Voi che per li occhi mi passaste ’l core

e destaste la mente che dormia,

guardate a l’angosciosa vita mia,

che sospirando la distrugge Amore.

E’ vèn tagliando di sì gran valore,

che’ deboletti spiriti van via:

riman figura sol en segnoria

e voce alquanta, che parla dolore.

Questa vertù d’amor che m’ha disfatto

da’ vostr’ occhi gentil’ presta si mosse:

un dardo mi gittò dentro dal fianco.

Sì giunse ritto ’l colpo al primo tratto,

che l’anima tremando si riscosse

veggendo morto ’l cor nel lato manco.

You who reached my heart through the eyes

And woke my dormant mind,

Take notice of the anguish of my life

That Love himself destroys with sighs,

And lays about him now so bravely

That my weakened spirits start to flee.

Only the head remains of the target

And a fractured voice to tell of grief.

This power of Love that has undone me

Came to me swiftly from your eyes.

He hurled the dart that caused me pain.

So fierce the blow arrived, and instantly,

Fearful the spirit shrank back in surprise

Seeing the heart within its left side slain.

Perché non fuoro a me gli occhi dispenti

Perché non fuoro a me gli occhi dispenti

o tolti, sì che de la lor veduta

non fosse nella mente mia venuta

a dir: «Ascolta se nel cor mi senti»?

Ch’una paura di novi tormenti

m’aparve allor, sì crudel e aguta,

che l’anima chiamò: «Donna, or ci aiuta,

che gli occhi ed i’ non rimagnàn dolenti!

Tu gli ha’ lasciati sì, che venne Amore

a pianger sovra lor pietosamente,

tanto che s’ode una profonda voce

la quale dice: – Chi gran pena sente

guardi costui, e vedrà ’l su’ core

che Morte ’l porta ’n man tagliato in croce–».

Why were my eyes not quenched,

Or stolen, so that from my seeing

Nothing came to my mind saying:

‘Listen, do you feel me in your heart?’

Fear of new torments’ beginning,

Filled me then, so sharp, cruel a blade,

The spirit cried: ‘Lady, now bring aid,

So my eyes and I are not left grieving.

You have left them: so Love may start

Weeping, concerning them, so piteously,

That there is heard a much deeper voice

Saying: ‘Who knows what pain may be,

Gaze on this man and view his heart,

Death bears in its hand, cut like a cross.

Tu m’hai si’ piena di dolor la mente

Tu m’hai sì piena di dolor la mente,

che l’anima si briga di partire,

e li sospir’ che manda ’l cor dolente

mostrano agli occhi che non può soffrire.

Amor, che lo tuo grande valor sente,

dice: «E’ mi duol che ti convien morire

per questa fiera donna, che nïente

par che piatate di te voglia udire».

I’ vo come colui ch’è fuor di vita,

che pare, a chi lo sguarda, ch’omo sia

fatto di rame o di pietra o di legno,

che si conduca sol per maestria

e porti ne lo core una ferita

che sia, com’ egli è morto, aperto segno.

You have filled my mind with such distress

That my spirit is minded to depart,

And my weary eyes display no less

The sighs that rise from the grieving heart.

Love knowing your great nobility

Says: ‘I am saddened you must die

Of this proud lady, she who hears only

What shows you pity with its sigh.’

I am like a man who leaves this life,

And, to those who gaze at him, is found

As if made of bronze or wood or stone,

Who in his heart bears a wound

That by its sole mastery is grown

To be of heart’s-death an open sign.

Full vocal scores can be found here.

[add_to_cart id=”31461“]

Sources and resources:

Bill Evans photo By Fauban – I made a photo, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36727292

Guido Cavalcanti, picture from the cover of Rime [Public Domain]

English translation of the poems