Introduction

Written between 1811 and 1812, the 7th is the only Beethoven’s symphony that aroused, throughout the centuries, the greatest variety of explanations. Beethoven himself did not give any indication as he did for instance with the 3rd, the Eroica, or the 6th, the Pastoral.

The most popular description was given by Wagner who, in conversation with Listz, called it “the apotheosis of the dance“. But many others tried to define what the 7th is about: Joseph d’Ortigue called it a procession in an old cathedral or catacombs (1863); for Adolf Bernhard Marx it was a tale of Moorish knighthood (1859); for Ludwig Bischoff was a sequel to the Pastoral symphony.

A Dr. Karl Iken, the editor of the Bremer Zeitung and a contemporary of Beethoven, read it as the depiction of a political revolution:

“The sign of revolt is given; there is a rushing and running about of the multitude; an innocent man, or party, is surrounded, overpowered after a struggle and haled before a legal tribunal. Innocency weeps; the judge pronounces a harsh sentence; sympathetic voices mingle in laments and denunciations. … The magistrates are now scarcely able to quiet the wild tumult. The uprising is suppressed, but the people are not quieted; hope smiles cheeringly and suddenly the voice of the people pronounces the decision in harmonious agreement.”

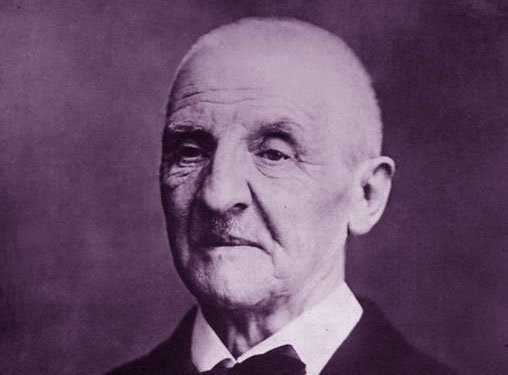

Portrait of the composer by Joseph Willibrord Mähler in 1815, two years after the premiere of the symphony

While some of these ideas might sound colorful, they do accentuate how different the interpretation of this symphony can be.

The 7th premiered in 1813, in Vienna, with Beethoven himself conducting. The occasion was a charity concert for the soldiers wounded in the Battle of Hanau – a battle fought between the Austro-Bavarian corps and a retreating Napoleon.

Beethoven Symphony n.7: an analysis of the 1st movement

Exposition

Poco Animato

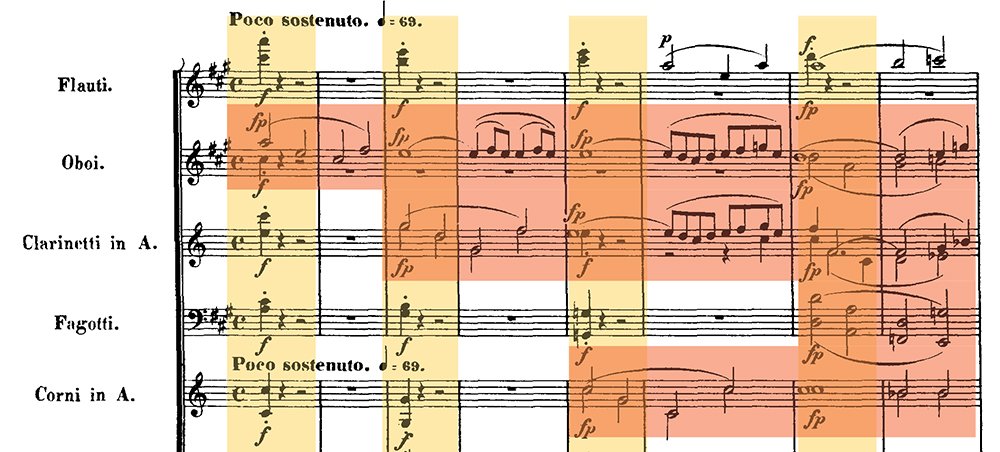

To realize the increasing importance of the woodwinds is sufficient to listen to the opening of the Poco Animato.

A full orchestra chord and then nothing, just an oboe with a very simple and lyrical line on an arpeggio.

What are we going to listen to? What do we expect? Something soothing perhaps given the gentleness of the woodwinds’ line?

It’s a decoy: it should be clear right from the first chord, ranging from the low A1 all the way up, that we’re in for something special.

Just so we don’t miss the point, Beethoven reiterates the strong chords a total of 4 times, falling back every time into a more reassuring gesture but adding each time an extra wind instrument. It’s a brilliant way to thicken the texture and widen the spectrum.

The strings are in the background, waiting patiently.

What Beethoven does is introducing us slowly to the rhythmical feast that is about to begin.

The violins, tentatively give us the rhythmic element of this slow introduction: a scale in 16th notes.

The question is repeated, and, with a big crescendo, we land on a tutti. The first motivic cell we heard from the woodwinds is now juxtaposed to the rhythmic material: only, now it’s bouncing between the 1st and 2nd violins and its character is completely different. Each note has a sforzato marking in fortissimo: Beethoven is asking the players to go beyond their loudest dynamic at the time.

We move to a new theme, suspended in the air, introduced, once again, by the woodwinds

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Vivace

The Vivace is in sonata form. The sonata form is a structure typical of classicism which normally includes an exposition with 2 contrasting themes, a development section where the musical material is tossed around and reworked, and a recapitulation. Everything is often framed by a slow introduction and a coda.

This movement is dominated by the lively dance-like dotted rhythms.

On top of that, it has the usual Beethoven’s fingerprints, such as the sudden changes in dynamics, and the abrupt modulations.

And guess who is presenting the first theme? The woodwinds of course!

There’s a bit of dialogue with the strings and then the theme is played in full orchestra. It’s a carbon copy of the structure used in the introduction.

Technical tip

When you get to hold on bar 88, do not close the hold or you’ll create an unwanted silence where Beethoven does not want one. Simply hold the sound and simply give a clear pulse for the scale.

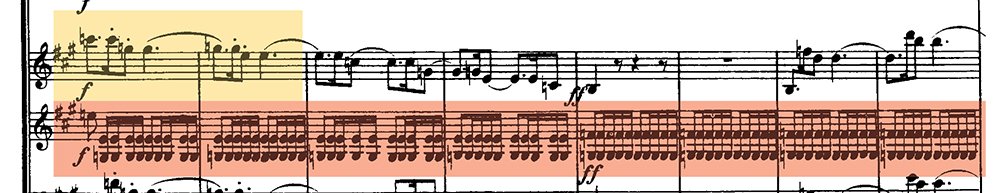

While we move on, the rhythmical element is omnipresent. And look at what pops back in 2nd violins and viola: the scales of the introduction, reversed

And then we stop. In which key? C major, the same one of that weird suspension we heard in the introduction. It’s another parenthesis

before a crescendo takes us to the end of the exposition

Development

The development section opens in C major again with 2 elements: the dotted rhythm and the scales. The scales crisscross each other beginning in each section 2 measures apart

And look at this: it’s the arpeggio we heard in the very first 2 bars. It’s now mixed with the dotted rhythmic cell

Technical tip

This is something that mostly depends on the acoustic of the hall but that comes in useful most of the time: wait a split of a second before the downbeat of bar 220. We’re coming from quite a long section of fortissimo and sforzandi and there’s a good chance of the sound carrying on with the reverb of the hall. If you wait that fraction of second, you’ll be able to listen much more clearly to the harmonic change in piano, without the overtones overlapping weirdly.

Recapitulation and coda

That same element takes us back into the recapitulation. By the way, notice the scales in the strings: besides being in 16th and ascending (connecting with the introduction) they also share the exact rhythm we heard on bar 88

The recapitulation proceeds with a few orchestrations changes, like the added timpani in this passage for example

or the change in the horns here

The movement finishes with a long coda, which starts similarly to the development section.

We’re suspended, sort of wondering where we are and where we’re going for a few bars, then a pedal of E spanning 4 octaves sets up the final crescendo. Notice this two-bar motive which is repeated 10 times

The rhythmic cell comes back, the horns pop out, gloriously, and the movement comes to an end.

In conclusion

One of the biggest performance issues that arise when interpreting this piece (along other Beethoven works naturally) is the issue of tempo. Beethoven at first thought of the metronome as “silly stuff“, insisting that “one must feel the tempo“. By 1818, he changed his mind and considered it indispensable.

Ultimately, he apparently arrived at a compromise explaining that the numerical tempo must be observed for only the first few measures because, and I quote, “feeling also has its tempo and cannot be expressed in this figure“.

Besides, it’s known that Beethoven owned 2 metronomes with inconsistent markings, and scholars disagree on which one was the “correct” one. From a conductor point of view, the metronome marking is a good indication but, ultimately, that’s all it is. What really counts is the feeling of it and the passion we can convey through this thrilling music. As Beethoven put it:

“Playing a wrong note is meaningless, playing without passion is inexcusable”

0 Comments