Introduction: the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

Pierre Boulez loved to say that the flute in this piece breathes new life in the art of music. It is, in a way, very simple and very complex at the same time, and it is certainly one of the most challenging pieces to conduct. By the way, here’s the full score if you don’t have a physical one at hand.

François Boucher: Pan et Syrinx, 1759

London National Gallery

Debussy was someone who played out of the box since his conservatory years, to much discontent and disapproval of his teachers: he felt that the harmonic world based on major and minor scales was too restrictive. Why not exploring different modes? Lydian, mixolydian, whole tone, octatonic scales. Incidentally, this set the way for a question that someone would pose later: why use scales and tonality at all?

In addition, he was highly influenced by a group of gamelan (the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia) who he saw in concert in Paris in 1889: his taste for colorful and exotic instrumentation has its germs in these typical sounds, rich in percussions of all different kinds. Combine this with his love for symbolism poetry and his love for painting and you’ll get a glimpse into what kind of world Debussy’s music was imbued of.

The story

Mallarmé’s poem (of which you can find a translation here) relates the dream of a flute-playing faun – half-man, half-animal: he awakes from a dream on a sultry afternoon with images of beautiful nymphs floating around in his consciousness – whether they are real or not we do not really know. After mentally trying to seduce them, the faun eventually sinks back into sleep.

Debussy never tells the story but rather suggests through his music Mallarmé’s descriptions of moods. This is what Debussy’s music is: you need to smell its scents, watching everything through a kaleidoscope of notes that let the imagination run wild.

Beginning the piece

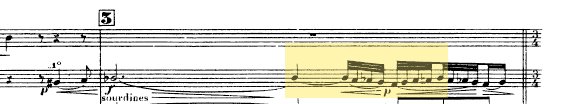

Debussy begins the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune with one of the most famous flute passages in the entire repertoire.

Technical tip

Do not conduct the flutist! Simply signal him or her that he/she can begin and start conducting in bar 4. Bear in mind that this whole piece is filled with “push and pull“, and your technique needs to be clear and flexible enough to switch between subdivided and unsubdivided gestures

Tonal center

What’s the tonal center of the piece? If, in fact, there is one? There’s been tons of books on the subject: Debussy tells us that it should be E major, which is, as a matter of fact, how the piece ends. However, he was known to blur the contours of tonality by mixing different scales. The first scale played by the flute, top to bottom, is already a triton, which to our modern ears might not sound special but for the time was pretty out there, especially because here it is not used in a moment of tension but rather in a moment of total calmness and relaxation. Then, on bar 4, Debussy introduces the Lydian scale, through the A#, only to use it as a bridge to a Bb 7, which normally should resolve on an Eb major; instead, being seeing as an altered 7th on the IV degree of the E major scale in lydian mood, it does not resolve at all, in a quasi perfect reminder of a Tristan chord.

All of this to say, that we’re 5 bars into the piece and Debussy has already thrown us around in his harmonic ventures without really leaving the initial key of E major.

How is this going to influence your conducting?

Very simply put, these incursions in different realms of tonality carry a different type of breathing: each phrase breathes differently and it’s going to either push forward all pull backward in order to allow for these subtleties to come through.

First section

Moving on, the flute theme is presented again, for another 3 times: each iteration of the theme is slightly variated, becoming more active, like the faun slowly waking up.

In the third and fourth iterations, Debussy also changes the meter and splits the strings up to 6 parts.

And look at the dynamics, carefully threaded to help out the balance of the orchestra, and let the swells come through without forcing.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

At number 3, the faun, now fully awaken in his dream, prepares to pursue the nymphs for the first time. The music changes in character while retaining elements of the flute theme: the chromatism of the clarinet comes directly from the first scale we hear at the beginning of the piece.

Notice also the horns with mutes, adding a raspy sound to this part. The excitement grows further when this 3 bars episode gets repeated a step and ½ higher. Then the music seems to relax a bit with the dolce ed espressivo of the oboe phrase: however the tempo gets faster and faster and in a few bars we are sucked into a vortex of emotions which go as quickly as they came, leading us into the second half of the piece.

Technical tip

Makes sure you respect Debussy’s dynamic markings and pace your accelerando and rallentando or you’ll have no place to go and instead of flowing it will sound forced.

The first section of the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune ends with a wonderful delicate clarinet on a carpet of strings: the music seems to rest but it’s a decoy as Debussy takes us again to a different world 4 bars after number 6.

Second section

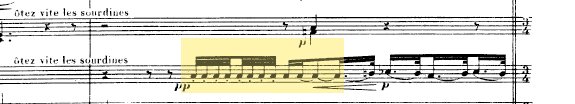

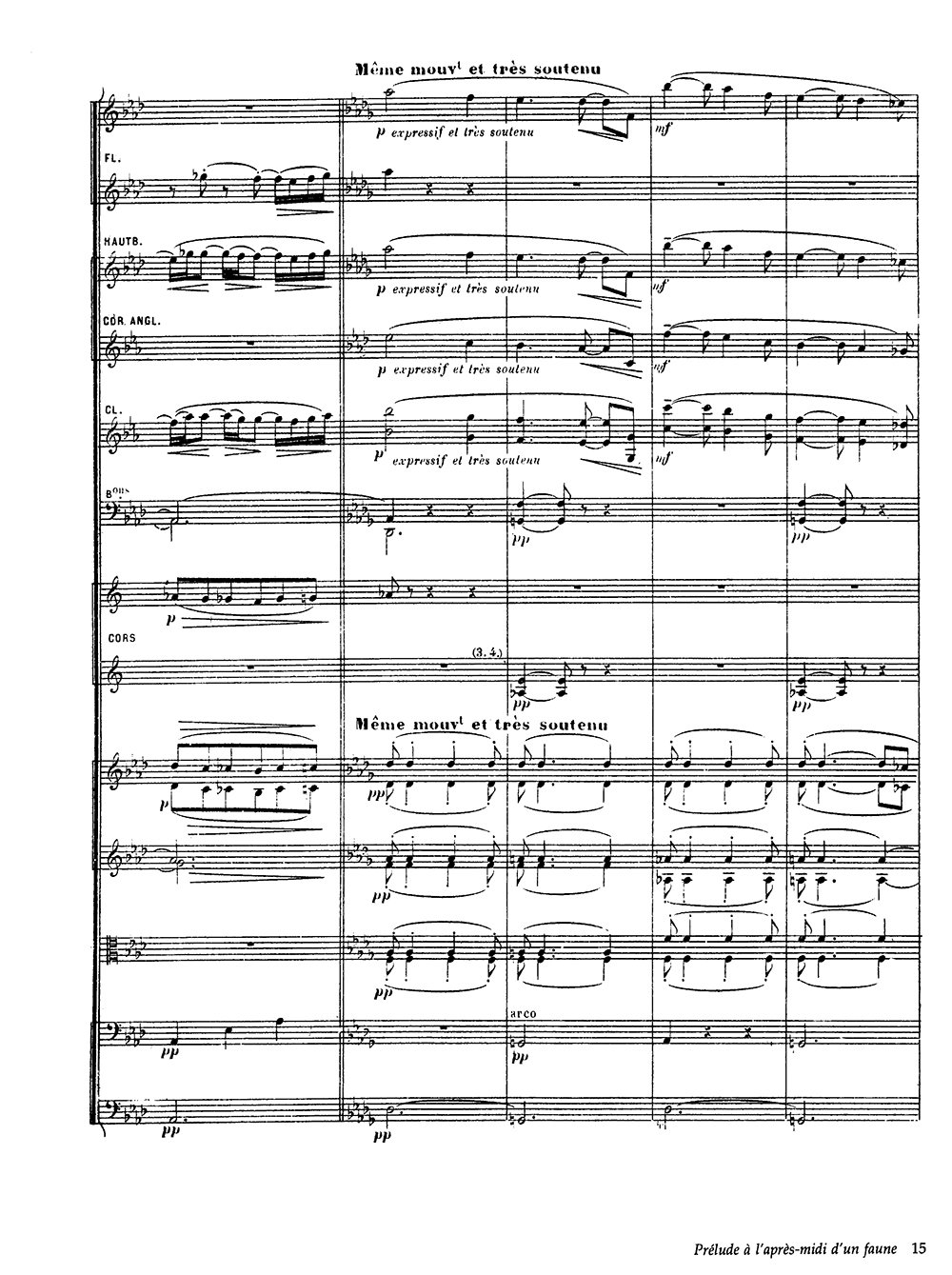

We are 55 bars into the piece. 55 out of 110, exactly half-way through when we hear a magnificent sensual melody played by the flute, the oboe, the English horn, and the clarinets, while the strings palpitate in syncopation.

Look at the dynamics: the woodwind in piano, espressivo, and very sustained, while everyone else is playing pianissimo. Notice the dots on the violins and viola parts adding the hearth-y detail to the accompaniment.

Technical tip

Register the woodwinds line downward, only with one hand; then make the crescendo at the end of the second bar and swap hands on the third. It will paint the blossoming of the music while remaining perfectly clear for the players.

You can see an example of this in the video below.

This wonderful theme is taken over by the strings. But the markings change – the strings are now marked very expressively and very sustained – and the woodwinds (with diminuendos every 2 notes) unbalance the overall rhythm with their triplets, while the harp gives us the underlying carpet with its flowing arpeggios. Again, everything gets more and more exciting for a few bars only to calm down with echoes of the various motifs in the violin solo, the horns, and the woodwinds.

Finale

Debussy slowly takes us back to the beginning of the piece.

At number 8 the first theme comes back in 4/4: why in 4/4 and not the original 9/8? Well, the theme might be the same but its character is different. In the beginning, the faun is waking up and the flute solo is almost rhapsodic in nature.

Here, on the other hand, the faun is about to go to sleep again. Incidentally, it’s much easier to go together with harp arpeggios with the theme in 4/4 than if it was written in 9/8, while maintaining the duality (and subtle tension) of triplets against duplets.

Mirroring the first part, we have another 4 iterations of the flute theme, with some variations, interjected by small episodes ending with little splashes of water (or at least that’s what comes to my mind when hearing those woodwinds).

On the third iteration, Debussy brings in the percussions for the first time in the piece. Naturally, it could have not been a usual percussion. Debussy opts for the crotales or antique cymbals, a rarely used instrument. Its peculiar sound adds another element of exoticism reminding us of that gamelan sound I mentioned in the beginning

Crotales

Technical tip

Subdivide the ritenuto before number 10, make eye contact with the percussion player and give him/her a clear cue

The music slows down further and further as our faun sinks back into his sleep. Notice the harp part: on number 12 it adds a natural rallentando by playing quadruplets in a 12/8. Two bars later, it colors the flute with harmonics, as the faun clauses his eyes on the last 2 pizzicatos of the cellos and double basses.

In conclusion

The Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune is undoubtedly one of the most challenging pieces of music to conduct: it asks for freedom and imagination, and definitely a solid technique. But it also offers an incredible amount of opportunities to shape your technique, to break patterns, and to convey your musical ideas with creativity.

A curiosity: this piece was conceived as a standalone orchestral piece, which is also the way it mostly played today. However, in 1912 it was staged as a ballet, choreographed by Vaclav Nižinskij for the Ballet Russe in Paris. It caused a riot, splitting the audience in 2, especially for the way it ended: since the faun couldn’t have his way with the nymphes, Nižinskijj envisioned him…enjoying himself before falling asleep…sex on stage came long before we can imagine… 🙂

0 Comments