Table of contents

Introduction

Known almost exclusively for the Sorcerer’s apprentice, Paul Dukas had quite an interesting career: he wrote very little music, and at one point he refused to keep writing, getting as far as destroying his own works. We are left with less than 15 compositions, of extremely high quality.

The Sorcerer’s apprentice is a symphonic poem written in 1897 based on a ballad by Goethe, and it’s pretty much all he is remembered for. This, despite the fact that he wrote one of the most beautiful and refined operas of the French repertoire: Ariane et Barbe-bleue. Another gem in his catalog is his symphony which is not performed nearly as enough as it should.

Notoriously, The Sorcerer’s apprentice was used in the Disney cartoon Fantasia. But the great popularity that it got from it also shadowed some of its unique characteristics, such as its structure and its orchestration.

The structure per se is a sonata form, like a movement of a classical symphony.

The sonata form is a structure typical of classicism, and it normally presents an exposition with a first and a second theme, a development section and a recapitulation. Everything is often framed by a slow introduction and a coda.

Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s apprentice: analysis

First theme

Here however, we are not going to find the usual 2 contrasting themes, a more masculine first theme, and a more feminine second theme (like we’ve seen in Beethoven’s Coriolan ouverture for instance). Dukas gives us 4 themes, all presented in the slow introduction.

The first theme, quite exotic in its harmonies, will see almost no development, except towards the end

This theme, very fluid in nature, is generally referred to as the “theme of water“: throughout the piece, its function is to connect sections together

Second theme

Right after, Dukas gives us the second theme, probably the most popular one, announced by the clarinet, then by the oboe, followed by the flute

Presenting the theme slower at the beginning of the piece is a smart composing trick: it allows the listener to get familiar with a fast piece at a slow pace. Exactly like practicing.

This is known as the theme of the magic broom. To keep practicing, the water theme comes back, followed again by the magic broom theme, and then Dukas changes pace.

Third theme

He gives us the third theme in a new Vivo section (vivo means lively by the way).

This one is the Apprentice’s theme: it’s full of the liveliness and cockiness of youth but also of its naivety.

Technical tip

Stop on the hold before the Vivo and give a very sharp upbeat. Keep it in the wrist and keep your stroke small: it will guarantee clarity and togetherness of the orchestra.

Fourth theme

We then go back to the slow part and then we’re thrown into the fourth theme

More than a theme this is a motive. It’s a call: every time the Sorcerer will pop through in the story we’ll hear this motive.

Notice how a part of the broom’s theme pops up under the sorcerer’s theme.

The idea of Dukas is brilliant: this is de facto a traditional slow introduction just like the ones we find in the classical symphonies. The musical material is introduced, bit by bit, or theme by theme, and once that’s finished we get into the actual story.

The introduction stops with a timpani strike. Then there’s silence: Dukas keeps the suspense.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Exposition

And then, the story develops in a sonata form, based, as mentioned, not on 2 themes but on 4. Even though, the function of the themes themselves is different from the classic sonata form: the water theme, for example, is never developed but serves as an interjection between the others, or as a connector; the sorcerer’s theme is a signal, appearing in very specific moments of the piece: at the end of the development and at the end of the recapitulation.

The other 2 themes are used as the 1st and 2nd theme of a sonata form.

The first is introduced by this kind of grotesque accompaniment, just a piece of it at first, then the rest

The theme itself is played by an instrument that traditionally can sound grotesque: the bassoon

the theme will be presented again, with a crescendo that will eventually reach the full orchestra.

The water theme is injected in the orchestral fabric and then this main theme is passed on to the muted trumpets

Once we get to the second theme, the apprentice theme, it arrives exactly in the key that we would expect it to be in a sonata form: the dominant key

Notice how this rhythmic cell, repeated a number of times, works as a glue between the second and the first theme. It is the same cell, rhythmically, we heard in broom theme, just reversed.

See how refined and thought out Dukas’ compositional style is? From this point forward, a sort of battle between these 2 themes begins.

The broom’s theme is back, on full orchestra

Development

There’s a sudden piano and the development begins. The themes keep confronting each other, interjected by the water theme. As in the best tradition of development, elements from the themes are taken and tossed around: the change of articulation is one of the first things that pops up. The staccato is gone and leaves place to a legato marking

Then the apprentice theme is back in full orchestra, after which the broom’s theme. But at one point, the accompaniment, very chromatic, doesn’t offer a stable ground and the music keeps sliding and shifting.

Technical tip

Split hands at number 36: use for instance your right hand to control the staccato of the woodwinds and harp. The smaller the stroke, the clear it will be. Your left hand can be saved for the violas and cellos line but the less you interfere with the orchestra here, the better it is.

Same goes for rehearsal number 38.

The climax of the development is signaled by the sorcerer’s call

See how Dukas shrinks time, giving the idea of the tempo getting faster? And he adds drama to it by climbing up the scale every time.

Recapitulation

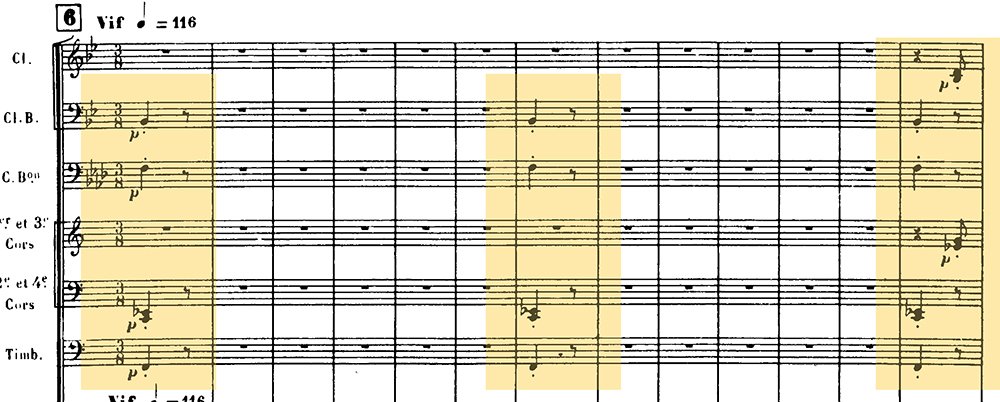

The tempo slows down gradually, in a quasi-static moment. The use of the contrabassoon first and then in combination with the bass clarinet makes the atmosphere even more grotesque.

Slowly but surely we slide into the recapitulation (also the moment during which the broom wakes up).

The battle of the themes is back once more until they overlap with one another

It’s a brilliant and highly skilled use of the themes in counterpoint. An idea that was really popular among composers of the late 19th century: the themes face each other at first, they study each other, get closer and then overlap in a synthesis of the musical thought.

After a final elaboration, the sorcerer’s theme erupts in the brass, all of them: horns, trumpets, cornets, and trombones. By the way, the cornet is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet: it differs from it for its conical bore, and in the mellower tone.

Coda

And then only the coda is left. The coda presents the themes once more, partially or completely: the water theme in the violins and viola, the broom’s theme is the bassoon, while a solo viola plays a fragment of the apprentice’s theme.

The themes are echoed in different instruments and the piece ends with the famous last broom stroke.

The Sorcerer’s apprentice, which at first might look like a very simple and entertaining piece, is in fact quite complex. Dukas manages to glue all the themes together in one way or another. Even the Sorcerer’s call is related to the others by a similarity in the interval.

We’re used to associating this composition with a cartoon when in fact it is proof of a highly skilled and refined composer. It’s a real pity for such a composer to be remembered almost exclusively for this single piece: it’s clear how much thought and skills there are in the composition of this work, both in terms of the formal structure and of the dramatic arch. Not to mention the highly imaginative and descriptive themes that combined with a masterful orchestration make this piece come to life in any concert hall.

Its interesting that some composers destroy the compositions. They were afraid of mediocrity or popularity? I think there was another composer but I dont remember the name, I watched it accidentally….as accidentally it was on tv.