Introduction

To understand the origins of Dvořák’s 7th symphony, we need to understand the time in which it was written: the Austrian-Hungarian empire in the 1880s was plagued by wars of culture, something that would become a weapon in the hands of the rising “ethnic activists“. Nothing really new: for a long time the empire had been going through tensions of various kinds with the Czech lands, and Czech people were often regarded as second-rate citizens.

Dvořák was caught in the middle of all of this. Despite the help he was continuously receiving from a real German – by the name of Johannes Brahms – him being Czech got in the way of his international recognition more than once.

Brahms was responsible for Dvořák’s first international success having passed the Moravian Duets to his publisher in 1875. This brought Dvořák a commission for the first set of Slavonic dances.

However, this was not enough for Dvořák: he did not want to be identified simply as a composer of catchy dance tunes. He wanted to enter the Olympus of composers and to get the same recognition Mozart and Beethoven had.

The political aspect

There was also a political dimension to this: the increasing racists’ trends were evermore trying to demonstrate the alleged superiority of the German people. It was somewhat believed that you could become German as long as you adopted the German language and customs.

That was considered a process through which the authentic Germans could civilize the Slavic people. As it’s easy to imagine this kind of thinking would give way to much bigger racist thoughts.

Dvořák set himself to change the course of it, or at least to try: his ambition was to be recognized as a “serious” composer of a “serious” German genre – the symphony; thus demonstrating that a Slavic composer could be as good as a German one.

This was what his 6th symphony was designed for. But the politicization of society went on increasing, pervading the cultural world with its ideologies, and the premiere of the 6th symphony in Vienna was dropped. The 6th got its premiere in Prague and then was brought to London with enormous success. The result was a commission by the London Philharmonic for a new symphony, in 1884.

It was the same Society that had commissioned Beethoven’s 9th symphony some 70 years earlier: you can imagine how prestigious it was for Dvořák to receive such a commission.

He determined that this new symphony would be more perfect than anything he had ever composed: more refined, more grandiose. The German people would surely have to acknowledge that a Czech composer could be just as good as a German one.

On the first page of the manuscript, Dvořák wrote that

“This main theme occurred to me upon the arrival at the station of the ceremonial train from Pest in 1884.”

Antonín Dvořák with his wife Anna in London, 1886

On that train, Czechs were traveling from Hungary to Prague for a performance at the National Theater.

The performance was followed by a pro-Czech political demonstration.

Antonín Dvořák Symphony n.7: an analysis of the 1st movement

Exposition

First theme

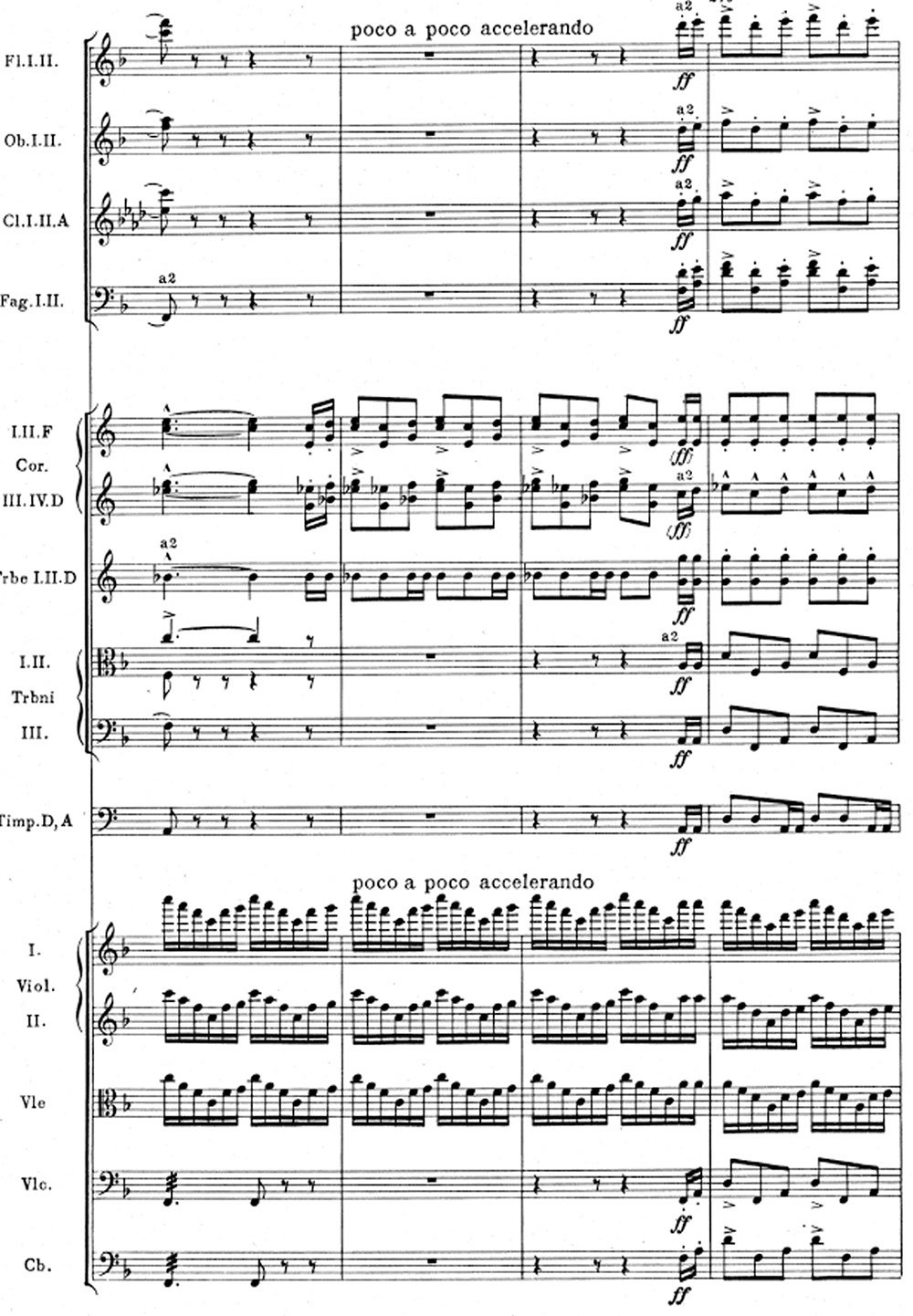

The structure is a typical sonata form: an exposition with 2 contrasting themes, a development, a recapitulation, and a coda.

The first theme is deep and dark: the violas and cellos take the lead at the end of the second bar but the atmosphere is set by a rumbling pedal of basses, timpani, and horns

The idea is repeated by the clarinets punctuated by the horn.

But look at how masters work: Dvořák takes the last cell of the theme, the 16th notes, and makes a slight rhythmical variation. And just from that, he acquires a new element that will come back times and again throughout the movement.

The strings bridge using those same rhythmic figures in a dramatic episode filled with stop and go.

Notice also the hemiolas, so typical of Czech music, blending the barlines and trampling the regularity of the meter

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Second theme

The second theme, in a lyrical and spacious Bb major, is sung by the flutes and clarinets and then picked up by the first violins – there’s a slight rallentando before their entrance by the way

While the second theme dies away, the first theme resurfaces. In fragments at first and then in full

The second theme is expanded to full orchestra leading to the end of the exposition.

Development

At this point, we expect a formal repeat. Notice the rhythmic cell, now expanded to 2 eight notes. Instead of going to a repeat, Dvořák uses this element to quietly plunge the music into the development. And look who’s up first: the second theme, now presented in B minor

Then it’s the first theme’s time.

All the elements come back, tossed around, and transformed in this tumultuous development. Look at how the first theme is fragmented in this passage for example

It’s a fragment, then a smaller one, then an even smaller one.

The development continues, growing ad growing and at it climaxes into the recapitulation

Recapitulation and coda

It’s a condensed version of what we’ve heard in the exposition and we’re swiftly taken to the second theme, in D major

The familiar sextuplets become increasingly important and at one point they get disrupted into hemiolas

Technical tip

It’s really important here not to lose control, or worse, go with the hemiolas. There’s a trick to that which has the bonus of not destroying the sound: once you’ve initiated the fortissimo, keep it small.

One bar after letter O, keep even smaller: nobody is going to drop their dynamics here. The rhythm will be tight and once you get to bar 280 there will still be enough room to have a fortissimo without making the sound harsh.

The sextuplet is retaken by the horns doubled by the violas in the final fortissimo

Given the premises, we would maybe expect the end to be loud and majestic: but Dvořák saves that for the last movement of the symphony. The coda fades away with a final appearance of the opening theme and all is left afterward is a shred of the rhythmic cell in 16th notes, making their way in the low register of the cellos with a rumbling timpani pedal on D, just like the beginning

In conclusion

The London premiere of this symphony was undoubtedly one of the great success in Dvořák’s life. In spite of this, when the symphony finally had its premiere in Vienna, in 1887, it was met with a cool reception.

Hans Richter, who conducted the Vienna performance, wrote to Dvořák:

“the symphony was not appreciated as much as I had hoped […]: our Philharmonic audiences are often, well, peculiar, to say the least!”

That same symphony is now considered one of Dvořák’s best works all around. It took some time, but his message finally got through.

0 Comments