Table of contents

Introduction

Mozart’s Symphony n.38 premiered in Prague, in January 1787. It needs to be noted that while his popularity was declining in Vienna, in Prague Mozart was a rockstar. His latest opera, The Marriage of Figaro, had had an enormous success. In a letter, Mozart wrote:

“…here they talk about nothing but Figaro. Nothing is played, sung, or whistled but Figaro.”

It’s possible that Mozart did not write this symphony with Prague in mind: the work was completed in Vienna on December 6, 1786, before he received an invitation to Prague. Mozart in that period was actually thinking about traveling to London.

But: going to Prague was something he could have not passed on. And this symphony became a gift to the city, which, in turn, gave it its nickname.

Le Nozze di Figaro: Cherubino hides behind Susanna’s chair as the Count arrives

However, there’s a couple of peculiar things that point in a different direction: while Mozart did not write the symphony in Prague, he might have kept as reference their tastes and aesthetics, perhaps hoping for a future trip.

For example, Mozart goes back to a 3 movement form, departing from the more common four-movement structure. The 3 movement form was typical of earlier symphonies but as the symphony as a form in itself evolved, so did its ambition to become greater and longer. Hence, the 4 movements adopted in the second part of the 18th century.

The 3 movements structure could be due to the simple fact that Mozart knew that in Prague they did not have a particular appreciation for Viennese dances (and therefore he cut the Minuet); or to the fact that the first 2 movements of the symphony are particularly extensive and a Minuet would have thrown off the balance of the entire symphony.

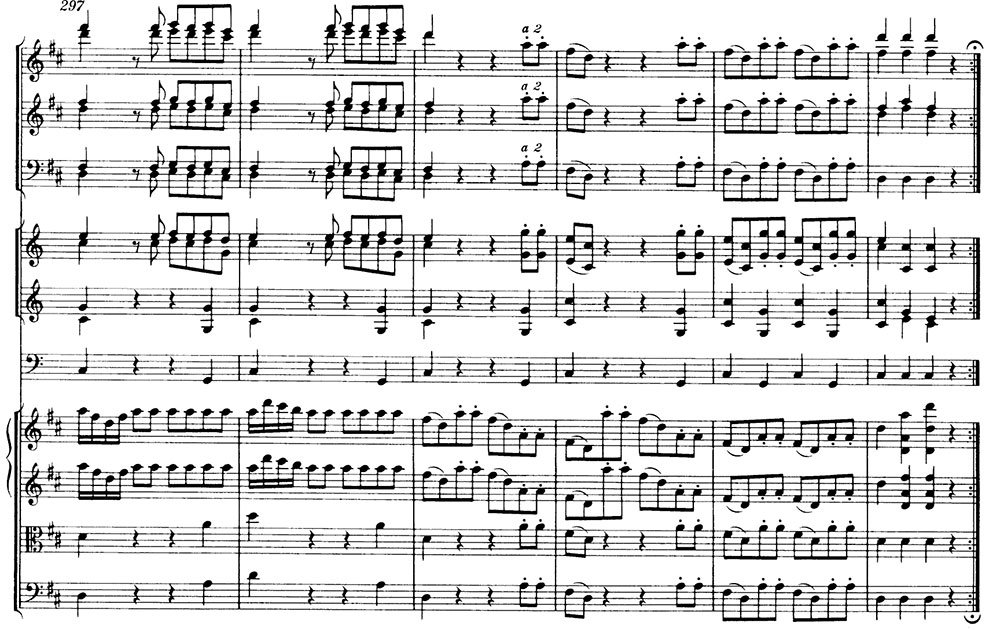

On another point, Prague was famed all around Europe for its wind players. Mozart, with the Prague, offers them more than a chance to show off, with so many passages where the strings don’t even play. And there’s the matter of the beginning of the last movement: a quote from The Marriage of Figaro (the little duet between Susanna and Cherubino in Act II).

Of course, all of these things could just be coincidental. We’ll never really know for sure.

Mozart Symphony K.504: an analysis of the 1st movement

Exposition

Adagio

The first movement begins with a slow introduction, something Mozart does in only 2 other symphonies (the n.36 “Linz” and n.39). Daniel Freeman has noted that it is probably the longest and most sophisticated slow introduction written for any major symphony up to that time.

It’s a regal D major. Except, we don’t know it’s major until the third bar, as the F or the F# is omitted the first 2 bars. As a matter of fact, the ambiguity of major/minor is a key factor of this introduction.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Allegro

First theme

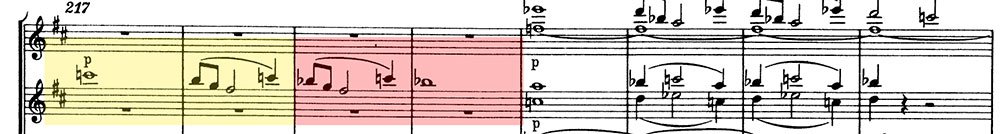

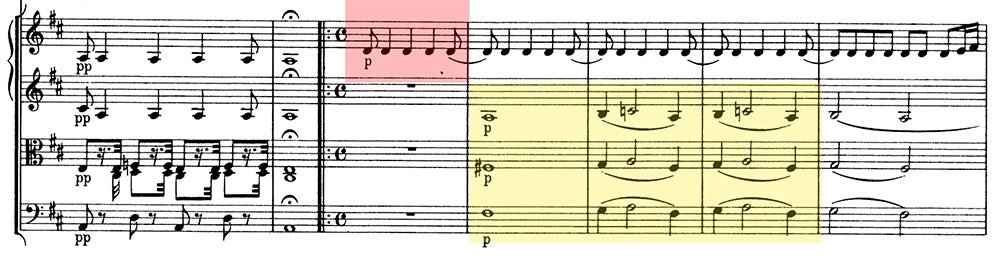

The Allegro begins with those same syncopations we’ve heard so many times in the introduction. It’s a composing trick: by repeating the same element a number of times, it is now firmly planted in the listener’s head and there’s an automatic reference to it. Notice how, once again, we don’t know if we are in D major or in D minor in the first bar of the Allegro. We only get the F#, and therefore the major key, on the second bar.

The entire Allegro is a major work of counterpoint: Mozart gives us an incredible amount of music material and he guides the lines one on top of the other in a masterful way.

The first theme it’s a syncopated in the lower strings with an immediate harmonic surprise: there’s a C natural in there

The rest of the orchestra answers the strings. Take notice of these 2 bars because they will be integral to the development section

Technical tip

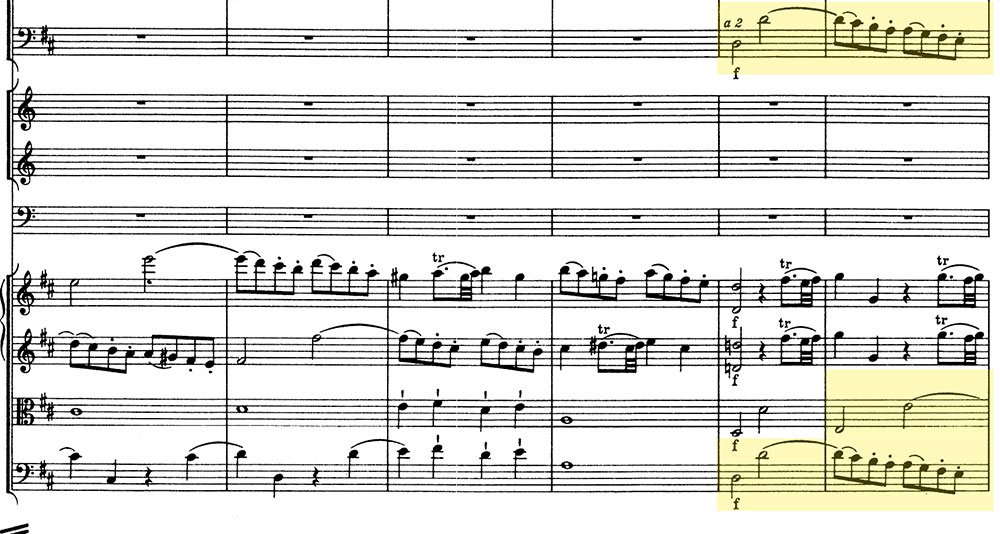

This is a perfect spot for visual score study. Just by looking at the score you can see that you have one element played by the strings and another one played by the winds.

You can replicate that by splitting the material between left and right hand. For instance use your right hand for the strings and your left hand for the winds. On the wind lines you can also register the jump of octave and the downward scale, adding an extra visual element to your conducting

By the way, you can go deeper into the chromatism used in this movement in the bonus material section

and we’re back to the syncopated theme with an added oboe line in counterpoint

Another surprise: a new line, derived partially from the introduction, is played by the violas and second violins while the first violins dance in counterpoint

It’s only 4 bars, and we explode in a forte with the full orchestra

We would normally expect a second theme after this section. But Mozart likes to play: he lands on the “correct” key of A major but he goes back to the first theme

and then interjects the other motivic elements

Second theme

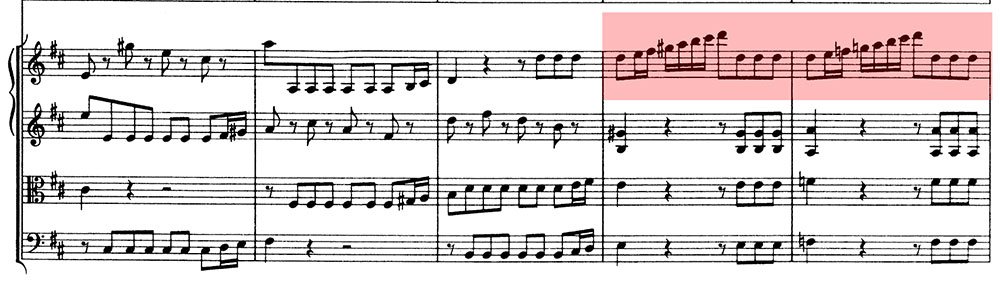

Lovely and cantabile the second theme is presented by the strings

and then repeated, again by the strings: this time, in minor, with the bassoons in counterpoint

The theme is reworked by the bassoons while the violins sit on top of it with a serene line

A short bridge takes us to a forte dynamic, where we hear the same material of the first forte in the Allegro. Only, the material is now moved from one section to another

Horns, trumpets and timpani introduce the first theme once more, in a glorious and powerful dimension

Development

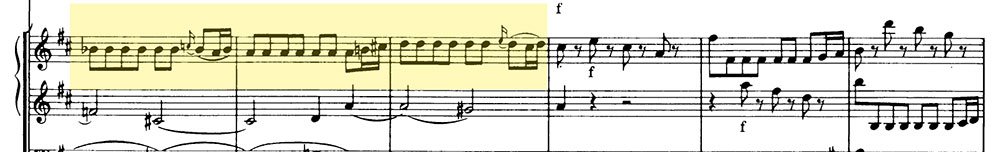

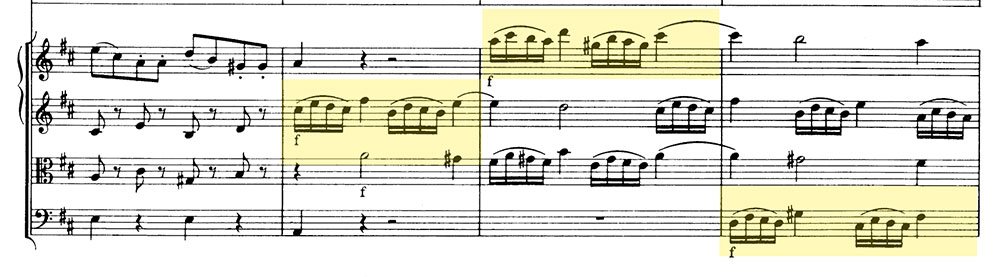

The development begins with a transposing game played on the answer of the orchestra to the first theme of the Allegro: first and second violins chase each other, going up a third every time. If you follow the 2 lines independently you’ll see that they’re playing an A major scale

The game is taken over by the lower strings and the bassoons

And now we should have the recapitulation. But no. It’s a false recap: Mozart keeps playing with both the musical material and the major/minor keys.

Recapitulation

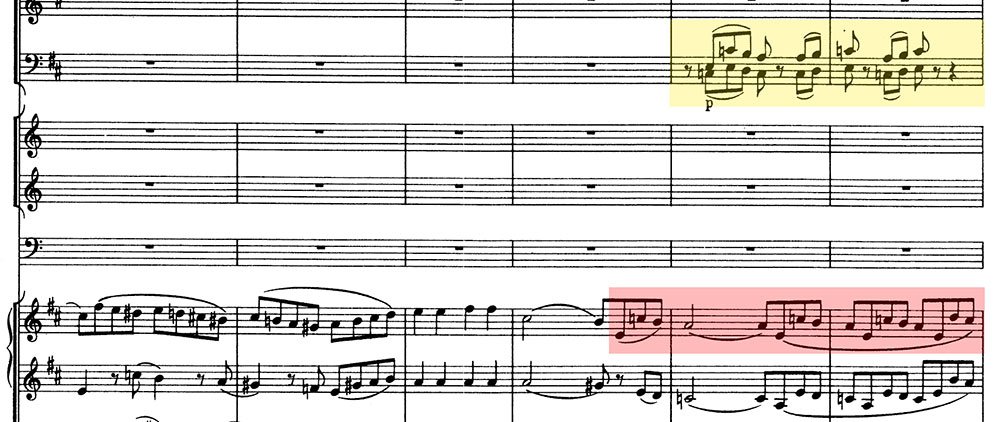

Already on the second repetition of the first theme, we have a change: the oboe turns from a B natural to a B flat

and the model is repeated to create a modulating bridge towards the forte. Notice how Mozart anticipates it by introducing a very familiar motive ahead of time

The recapitulation is contracted, without another repetition of the first theme. And we happily land on the second theme in D major

Coda

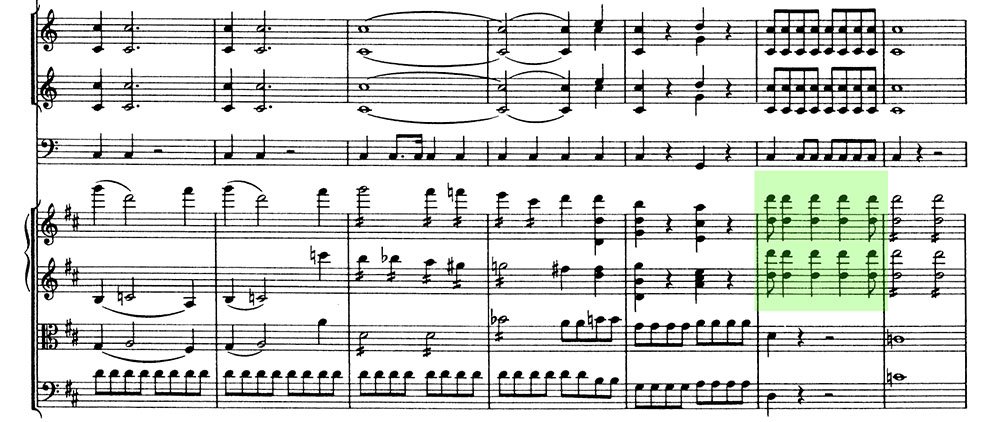

In the coda, the first theme comes back twice, making up for its “missed” third repetition in the recapitulation. And look at what’s underneath the horns, trumpets and timpani the second time around: the very first bar of the Allegro

Technical tip

When you get to this point, either here or in the exposition, notice that there is no change in dynamic. Therefore your gestures here should not become bigger.

While you can underline the change in the music, there is no need to over-conduct: once you’ve initiated the forte dynamic, keep small and let the orchestra play.

The “change of dynamic” is already written in the orchestration with the violins playing in the higher register.

after this, the movement triumphantly ends in its home key

In conclusion

As I’m sure you’ve noticed, Mozart’s Prague is an exceptionally crafted work: the way all the lines come together in a crystal clear counterpoint anticipate another work sharing the same architectural concept: Mozart’s last symphony, specifically its last movement.

There’s an abundance of invention in this first movement. It’s a challenge that Mozart posed to himself: to take all of this turbulent and fizzy material and transform it into something cohesive. It goes without saying that he succeeded.

0 Comments