Introduction

Leoš Janáček is a chapter on his own in the history of music: he is one of those musicians that came out of nowhere and left like a comet. One cannot really trace a school he belongs to nor a composer who followed in his footsteps. In that respect, it’s much easier to see a continuation between Mahler and Schoenberg for example. Sure, it’s often said that Janacek was heavily influenced by Dvořák. But that is limiting and to define Janáček as the natural musical prosecution of Dvořák is inaccurate.

While I’m not trying to diminish the importance of previous composers in Janáček’s music, he is a composer who found his own unique language that nobody could anticipate and nobody would try to imitate afterward.

I remember the first time I had to deal with his music: it was during the Bard Music Festival dedicated to him back in 2003 and as an assistant conductor at the American Symphony Orchestra I was preparing one of his operas: Osud (Fate). I’ll admit that it was everything but easy. But when I learned that in his lines he was trying to imitate the natural human speech, things started to make a lot more sense. Even more when the relationship between his seemingly weird harmonies and the text became evident.

Taras Bulba: illustration for the novel by Pyotr Sokolov, 1861

Janáček’s harmony is not straight forward, at least not at first hearing (or sight). But digging a bit deeper, one can recognize his fingerprints and a whole new world is suddenly revealed.

One common element to his writing relies on the use of the 9th and 13th within regular chords.

Janáček’s gift is not expressed in inventing new chords but in exploiting different angles of old chords making them some new. He does this through voicing, orchestration, and through the addition and/or subtraction of certain notes within the chord. We can see this right at the beginning of Taras Bulba.

Janáček Taras Bulba: an analysis of the 1st movement, the death of Andrei

Taras Bulba is among the most significant works for orchestra alone by Janáček; composed between 1915 and 1918 (so during World War I), this work expresses the composer’s admiration for the indomitable spirit of the Russian people. At the same time, he makes clear the will of his compatriots for a Czech nation, free from the domination of the Austrian empire.

Janáček was a fan of Russia: he even founded a Russian Club in Brno in 1897 and later on sent his children to Saint Petersburg to study. He loved, naturally, Russian writers like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky but Gogol had a special place in his heart and mind. As a matter of fact, Janáček had started thinking about writing music based on Gogol’s tale of Taras Bulba (defined by Hemingway as “one of the ten greatest books of all time”) as early as 1905.

Janáček places the accent on 3 episodes of the life of the Cossack leader, all of them referring to death: that of his sons Andrei and Ostap and then that of Taras Bulba himself.

They are, in fact, 3 symphonic poems, framed under the title of Rhapsody for Orchestra, a form that traditionally is a one-movement piece.

The first movement focuses on Andrei, Taras Bulba’s first son, who, in love with the daughter of a Polish general, becomes a traitor and goes fighting into the enemy ranks. The father confronts his son in battle, renounces him, and kills him.

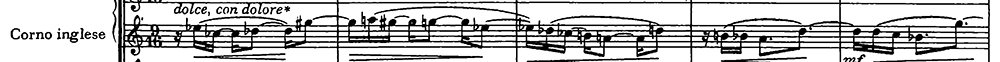

The movement begins with a soothing melody played by the English horn, representing Andrei’s vision of his lover

Janáček’s peculiar way of treating the orchestra and the harmony starts right away. Look at the first chord. It’s F# minor, but we only know that for sure at the end of the bar.

The chord is built from the ground up: a low F# in the basses and cellos in octaves; then the 3rd of the chord in violas and second violins, again in octaves; then the 1st violins with the F# and the A. The 5th is missing. The strings begin with this spaced out chord just a split of a second before the English horn, whose melody begins on the 9th of the chord, the G#. Only at the end of the bar we finally get our C#, the 5th of the chord.

Have you noticed something? This music does not begin. When we start hearing it, it has already begun, somewhere else. We’ve been catapulted in a different universe altogether. The music just is, and we’ve simply turned the volume up.

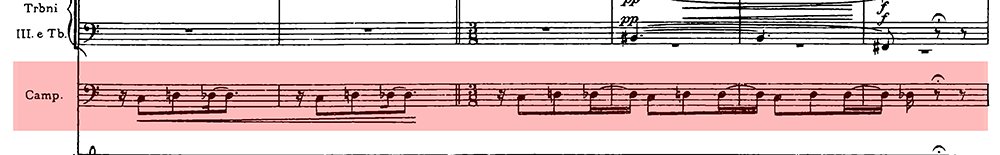

This does not sound like a love song: it’s more mournful than anything else. Janáček throws us inside Andrei’s conscience. The troubles are punctuated by dissonant bells

and the organ has a prominent solo part

All the turmoil we experience in this quicksand-type-of-beginning explores Andrei’s internal and intimate battle. Notice how the lovely theme is passed from one instrument to another, reaching as low as a solo double bass.

The love scene is transformed: the exact same element now acquires a very different character, kind of spooky

The phrasing gets very interesting and intricate: we start with a simple 4 bars phrasing but once we become accustomed to it Janáček throws it all in the air: we go to 2 bars phrasing, then 3, then 2 and 3, then 2 and 2 and so on. The unpredictability of this phrasing adds tension and drama to the music.

Technical tip

This is unwritten but traditional: one bar before number 4 make a rallentando and conduct that bar in 3. This is done in order to establish a clear tempo at the Adagio (which by the way is in 2) while keeping the D# in the violins as part of the new phrase.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

We’re thrown back to a love scene, more serene, with a hint of passion between the 2 lovers

It’s just a dream: the cymbals hit with a wooden drumstick prevent us from sliding back into it

We try to go back but an ominous music tells us otherwise

We try again, but there’s no chance. The dream turns into a nightmare. The trombones introduce Taras Bulba, the fierce battle begins and we witness father and son tragically confronting each other.

The battle is underlined by the bells, the off accents that trample the regularity of the rhythm; and of course the dynamics, going from forte to sforzato to fortissimo to sforzatissimo.

The triumphal line of the trumpets takes us to Andrei’s death

Then silence. Dramatic silence, suspense.

There’s a brief reprise of the love theme. Was it all a dream? The horns with sourdines with the battle rhythm tell us otherwise

The dream is over with the final Presto, punctuated once more by those bells. By the way notice how the bells play always the same 3 notes throughout the piece, anticipating since the beginning the tragic end

In conclusion

Janáček’s music can be rather challenging to digest at first hearing. But once you pass beyond the first apparent barrier and start looking at the chords and at the music as musical depictions of a character’s thoughts or words, a totally new world opens up.

The oniric dimension pervades this piece even when reality lashes in bombastically. It’s unsettling. And that’s the magnetic power of a composer that was once looked at as an eccentric provincial and is now rightfully regarded as one of the most creative figures of his time.

0 Comments