Table of contents

Introduction

Born as a piano piece, the Pavane pour une infante défunte (Pavane for a dead princess) was written in 1899 by a young Ravel (Ravel was born in 1875), still a student at the conservatory in Paris at the time.

Ravel described the piece as “an evocation of a pavane that a little princess might, in former times, have danced at the Spanish court“. The princess is a figment of his imagination and indeed, the only real princess involved was the Princess Edmond de Polignac (born Winnaretta Singer), a noted patroness of the arts, to whom Ravel dedicated the piece.

The link to the Spanish court is clearly specified in the title, with the word “infante“, a title given to the children of the kings of Spain and Portugal who were not the elders. The piece falls within the lines of that renewed passion for Spanish music shared with some of the composer’s contemporaries. Which was helped of course by some very well known Spanish composers like Albéniz and de Falla.

But the link is not just a geographical one, it’s also a temporal one: the pavane was a dance typical of the Renaissance and became extremely popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. The choice was not made by chance: Ravel’s teacher, the great composer Gabriel Fauré, had written a famous pavane for orchestra back in 1887.

Ravel orchestrated his pavane much later, in 1910 and it is to this day one of his most popular pieces. It is a relatively simple piece, especially when compared to other works by Ravel who endure the same popularity, like the Suite from Daphnis et Chloe or his Piano concerto in G.

Ravel plays Ravel: 1922 piano roll of the Pavane pour une infante défunte

In fact, Ravel in later years tried to distance himself from it. He felt that it stole too much from Chabrier, and complained that its construction showed “quite poor form,” and was “inconclusive and conventional.“

By the way, Ravel himself made a piano roll recording of it in 1922 and supervised the recording of the orchestra version of 1932.

Ravel’s Pavane pour une infante défunte: analysis

“A” section

The Pavane is a very soft piece: and I don’t mean just in terms of dynamics. It’s soft in asperities too (and here’s the heritage and another influence of Fauré): wherever there are dissonances they are never sharp but always round on the angles.

The structure is also very linear: A B A C A. The real sophistication comes with the orchestration of which Ravel was an absolute master.

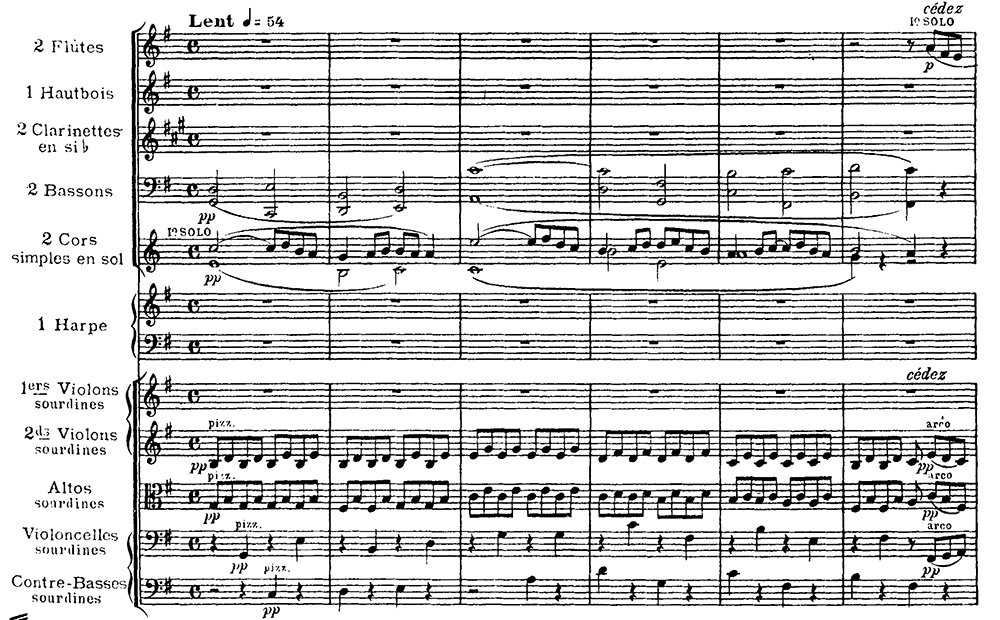

Take a look at the beginning: the strings, always muted, accompany a solo horn, like little drops of rain on this melancholic phrase. The horn, which usually has a very warm sound, here is almost cold when compared to the warmth of the flute and strings answer at the end of the phrase.

And the harp, so beloved by Ravel and Debussy, opens the phrase for a moment.

Until horns, clarinets and bassoons put a darker shade on it and lend it over to the oboe which introduces the B section.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

“B” section

By the way, interestingly, while all the other woodwinds and the horns are in the usual pair, Ravel calls for only one oboe.

Technical tip

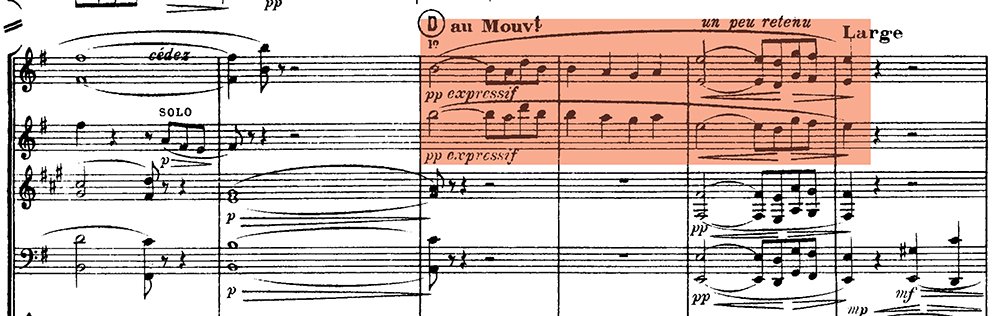

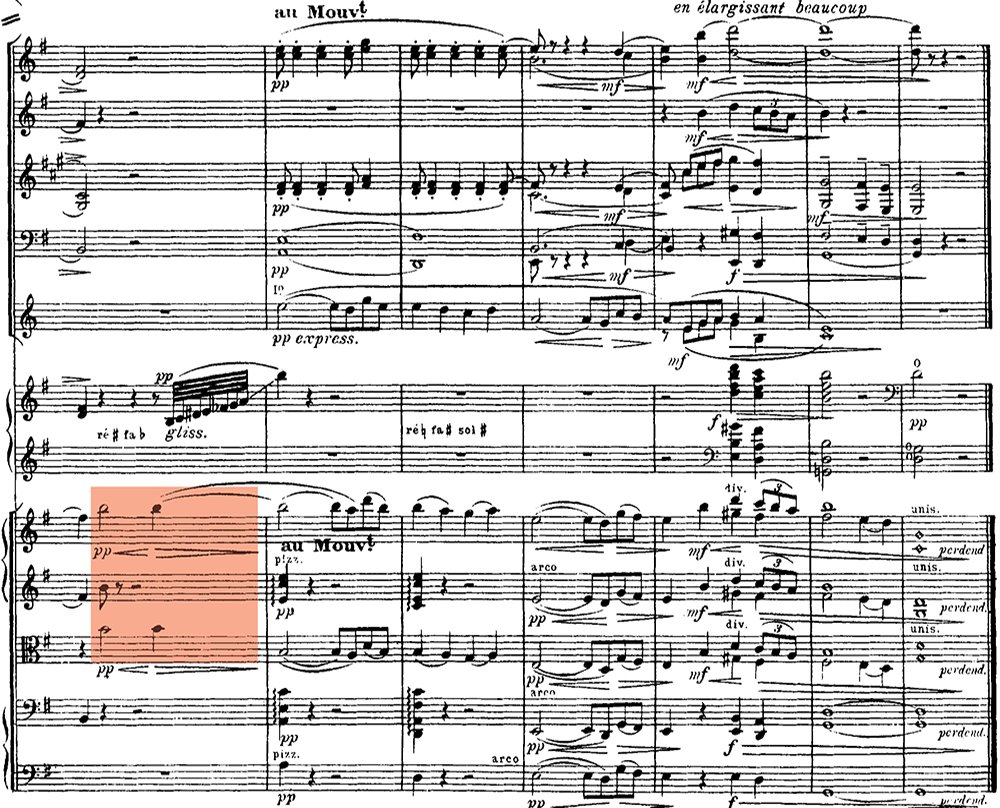

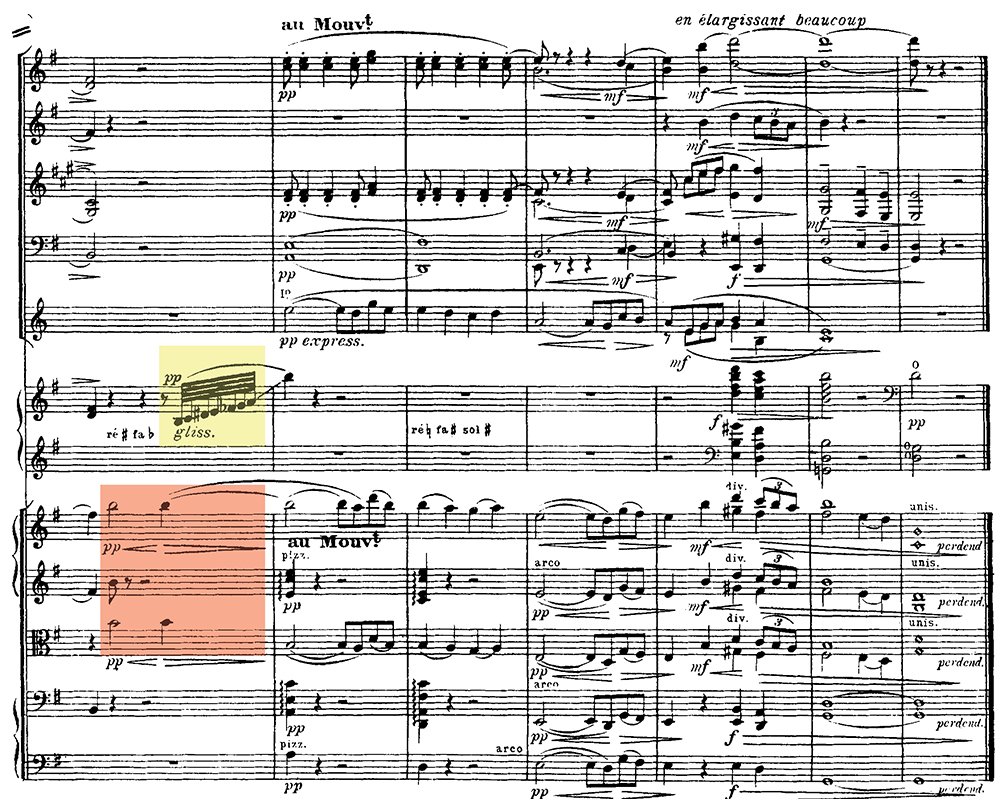

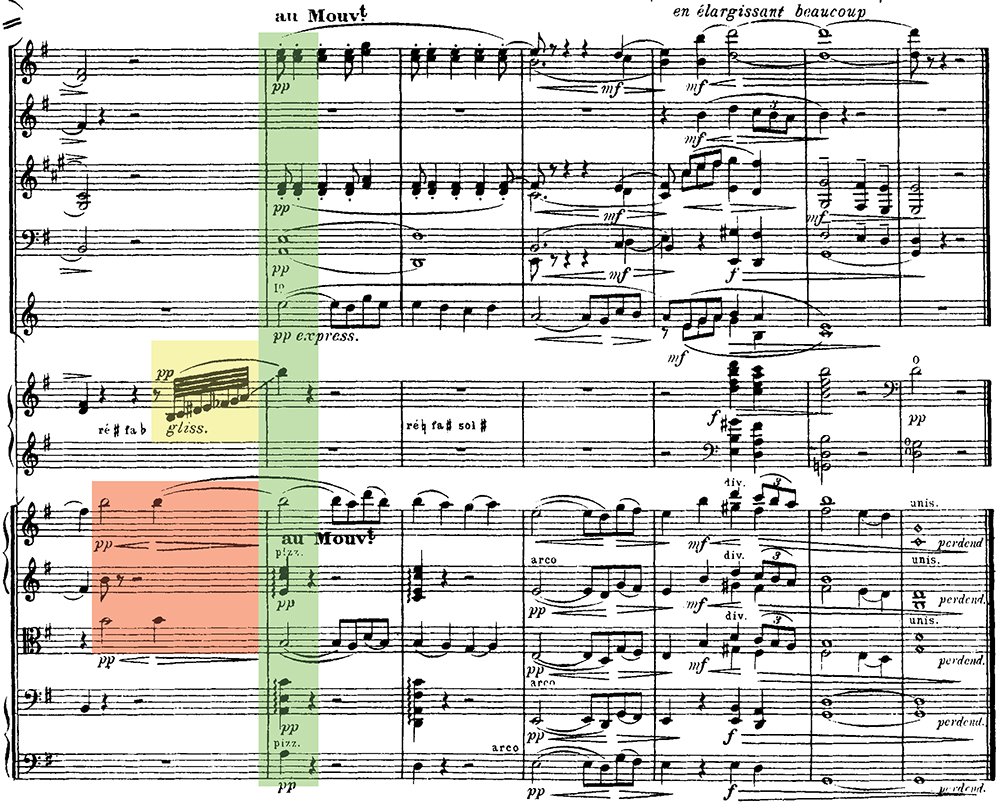

Notice all the tempo indications Ravel puts in the score: he starts with Lent (Lento, slow) and then adds cedez (give in), au movement (A tempo), en elargissant (allargando), then back to 1er Mouvement (Tempo primo).

This alone will give you the idea of how flexible you need to be in order for the piece to come to life: you need to breathe it and let all the nuances come through naturally.

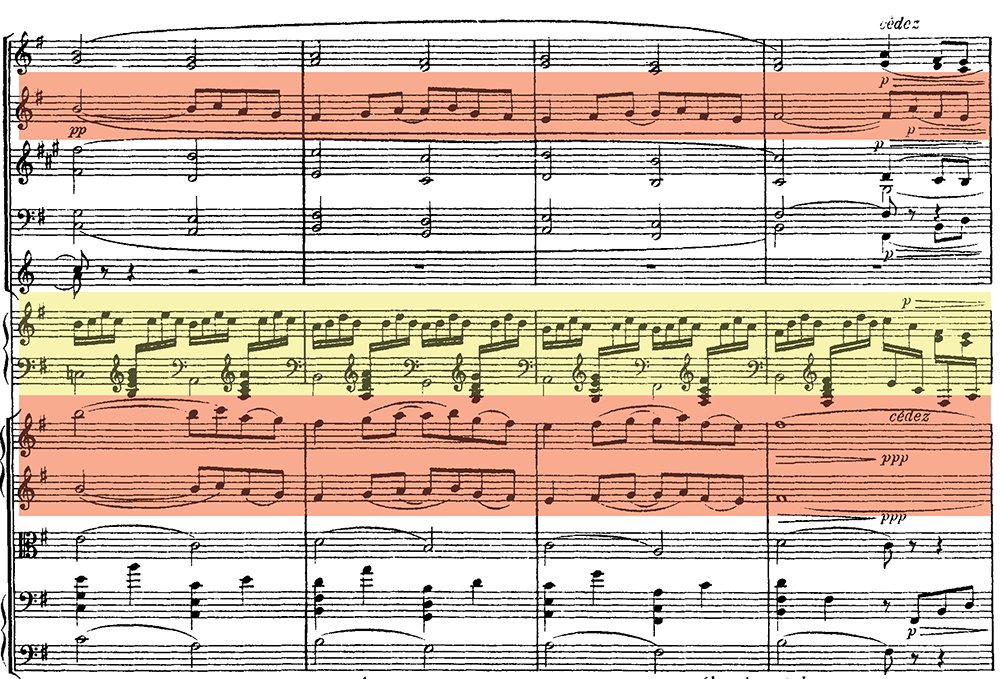

The harp, again, underlines the atmosphere with its low note pedal. This second theme is repeated by the strings, with a pizzicato of the double basses

Second “A” section

Everything is still, there are no contrasts between sections or instruments. And we’re taken back to the A section again, with variations: the theme is now played by flutes and clarinets in octaves

and the oboe joins in, coloring the phrase.

The harp again, and then the genius of Ravel places the oboe an octave above the flute

Normally the flute is placed higher than the oboe due to its nature. But listen here how it helps in creating a distant and somewhat somber moment

“C” section

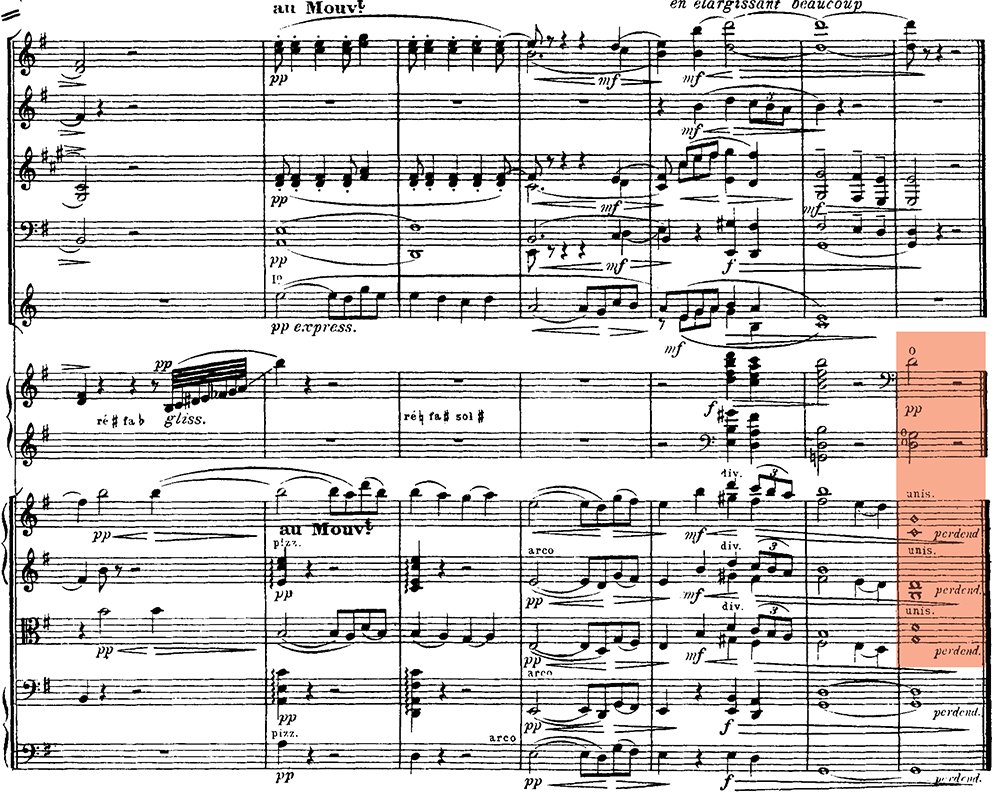

and then the warmth of the strings encouraged in their gesture by the clarinets and the oboe. The music seems to grow for a second, creating a certain expectation to get bigger. But instead, it folds on itself, and its delicacy returns like a caress. In this entire section the harp is always present in the background, painting dreams with its arpeggios and glissandos.

Third “A” section

Until in the last repeat of the A section, the harp becomes a key player of the accompaniment on top of which the melody flows played by the violins doubled by the flutes and then by the oboe.

Technical tip

The dynamic here is still pianissimo. But Ravel takes care of it with the orchestration: with the violins in octaves, it already sounds louder and more open. It’s very easy to fall into the temptation to make unwritten crescendi and diminuendi. But that would take away from the dreaminess of the line making it over-romantic.

And listen to how a single note gets colored by different instruments: first the violins, then harp, then the rest of the orchestra.

The phrase closes on the last chord in harmonics, ending this extraordinary moment of a Princess life with ethereal grace.

You descibe it like doing the painting, like each instrument creates different color, shade and it creates mood. 🙂 ….Structure is either the dynamics or callmness? ….like the dynamics or calmness in paintings.:) I only guess…My mom used to draw, now she is experimenting by doing paintings, but static, no dynamics.Music can not be static 🙂 She doesnt seem to be satisfied in the process. Drawing seems easier..I dont know how to describe music, but only to say classic music is rarely boring, with all the possibilities. 🙂 Only our mind may be bored. 🙂 But to me ding painting is easier than classic music. You may paint some abstract “nonsese” with one color or two colors only, in short period of time, put it in gallery, as we saw on tv, and somebody will say that its artwork. 🙂 or you paint something extremelly beautiful, and somebody says its beautiful too…but I doubt that in classical music its possible. You need talent.

It is not common for masters to be often photographed in their environment. It gives space for imagination. 🙂

yes, it’s fascinating, isn’t it? 🙂

I put a few other pictures on my FB page:

https://www.facebook.com/ggriglio/posts/3147964065324511

Yes. I saw the pictures and the gallery of previous composers.. They have always calm or neutral face, like they are thinking of something.Maybe they didnt want to move too much to be blurry in picture.

It also was not custom to smile in pictures (as in paintings). That is something that came much more recently

Its interesting. Actually you are right. It seems Tchaikovskyin the picture in the garden was almost smilling.

“But that would take away from the dreaminess of the line making it over-romantic”…What is over-romantic? too melancholic? or sentimental maybe.

In this case, if the dynamics are pushed over what’s written they would tear the airiness of the line. Big contrasts in dynamics with warm and luscious crescendo and diminuendo is something that’s typical of the romantic and late-romantic period, which does overlap with the impressionism (in music) of which Ravel is part. These are the same years in which Mahler is writing his symphonies, and Puccini is jumping from Manon Lescaut to Tosca via Boheme. But this piece by Ravel does not belong into that category: it calls for subtle changes and a very gentle approach

Thanks. You always have perfect explanations. Like poetry 🙂

Thank you, that’s very kind of you

Conductors talk of Mahler a lot..there are lot of titles of concerts….and Shostakovich and Stravinsky. But some complain that many american composers of 20´century are forgoten or unknown for public or that there are the ones who did symphonies and the ones who didnt. Maybe ts also fact that is a lot of material to study.

Well, those 3 you mentioned are pivotal in the history of classical music. While that justifies the amount of interest in them, it is true that it overshadows other composers. But that can be true for a single composer as well: Dukas is almost exclusively known for his Sorcerer’s apprentice, while his other works (like his symphony) have been totally dismissed (with the seldom exception of his opera Ariane et Barbebleu)

Its good that they are pivotal and often presented because of what they created and the symphonies..and I said two comments in one. They discuss or they asked G. Schwarz now during quaratine also why some american composers are not played, or just few of them and also discussing the money to make it happen, and people´s willingness to go to concerts that ts important to have audience who use to come etc. And some lady asked what to do when musicians have nothing to do now…he said listen music or read a book as he does. It seems people try to find some inspiration to stay positive.

Indeed they do. Even if it everything but easy for a lot of us who are musicians and performers in general.

Yes its little emotional too, too many problems in the world. But when we focus on something else, we feel better.

In the video Ravel is playing by himself. Its relaxing.

Mahler was mostly conductor too, did it for living. Conductors get inspiration from him.

he was one of the best conductors in the world. Pity there are no recordings…

He is role model for conductors. Its interesting. It seems the radio wasnt fully invented maybe.