Introduction

As much as Franz Liszt is one of the most prominent figures in classical music, his popularity is largely due to his skills as a pianist and to the extent to which he took the piano technique in his compositions.

And yet, like all geniuses, he had a fervent imagination who took him in different directions throughout his life.

One of his goals was to redefine symphonic music: in short, the creation of a programmatic piece that would incorporate a story, or a mood, and combine the form of the Ouverture and of the first movement of a classic symphony.

The result of this research is his 13 symphonic poems, a new symphonic genre in one movement, and tied to a specific subject, like Tasso, or Prometheus, or Orpheus.

Franz Liszt in 1858

The Dante Symphony, as well as the Faust Symphony, shares the same aesthetics. Even though they are in multiple movements the compositional approach and their aim is the same. By the way, the idea of telling a story in music, describing a situation, an emotion, or a character is a concept that was very dear to another composer, Richard Wagner.

Incidentally, Wagner and Liszt knew each other very well, having Wagner married Liszt’s daughter Cosima. If you travel to Bayreuth, Wagner’s temple, you’ll be able to visit both Liszt and Wagner’s houses, which are facing one another and have now been turned into museums.

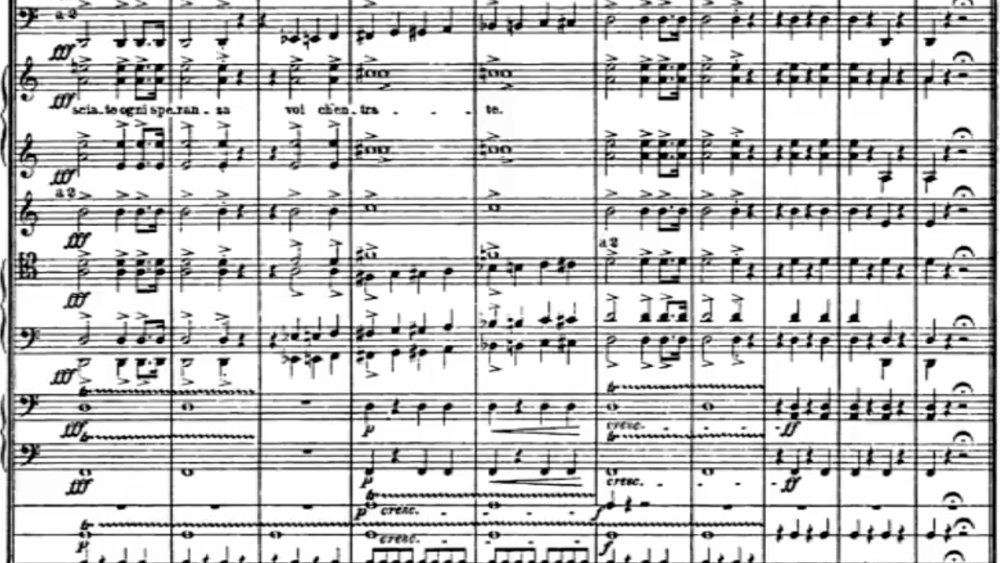

The Dante Symphony

Despite the title, this work is not really a symphony, at least not in the classic sense of it.

Liszt had started sketching themes for this work since the early 1840s:

“I will undertake a composition based on Dante’s Comedy.”

In 1847 he played some fragments on the piano for the Polish princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, his lover; Liszt cultivated the idea of projecting scenes taken from the Dante’s Comedy and painted by Bonaventura Genelli during the concerts, as well as the use of a “wind machine” to recreate the whirlwinds of Hell at the end of the first movement. The princess was willing to bear the costs of this effective staging, but things eventually did not work out.

Liszt took up the work again in June 1855 and completed most of it by the end of the following year, roughly the same period of composition of the Faust-Symphonie.

In October 1857 Liszt played both the Faust Symphonie and the Dante Symphonie on the piano in Zurich, at Wagner’s home, who was very skeptical about the fortissimo at the end of the second work, which he considered unsuitable for the idea of Paradise. Liszt had to agree since his original intention was to conclude with the movement dedicated to Purgatory, but Princess Carolyne had persuaded him to add a hint to the glory of Heaven. On the autograph, however, Liszt rewrote the last bars but left to the performer the choice of whether to add the fortissimo ending at the end of the pianissimo.

The premiere of the symphonic poem at the Dresden Hoftheater, on November 7, 1857, shortly after the conclusion of the composition, was a disaster because of the absolutely inadequate rehearsals; Liszt, who had conducted the orchestra himself, was publicly humiliated. This did not prevent him from preparing better the next time, March 11, 1858 in Prague, with the distribution of a program that prepared the audience for the unusual form of this two-part composition.

The Dante-Symphonie is in fact a work that presents important innovations with respect to the performance practice of the time: just think of the fact that it begins in D minor and ends in B major.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

The vestibule of hell and Limbo

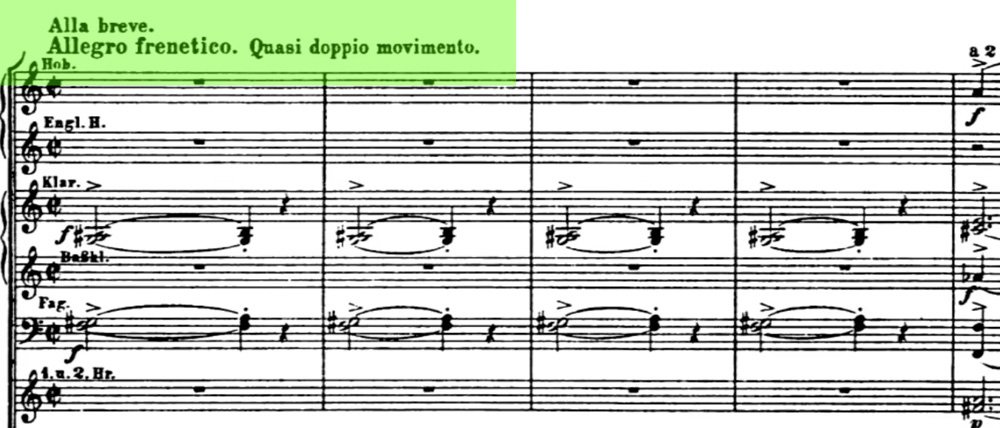

It starts in D minor, again, but the key seems ambiguous. This accelerating section reaches a frenetic Allegro at the climax. Look at the tempo marking: it’s literally marked Allegro frenetico which gives you an idea of how unsettling the atmosphere needs to be. The theme is also derived, quite obviously, from the same ascending and descending semitones idea we heard in the introduction.

The tempo increases to Presto molto and a second subject is played by wind and strings over a pedal on the dominant A:

No references to Dante’s verses appear in the score, but it is quite reasonable to imagine this exposition as representing the Vestibule and the Limbo, the scenario that opens to Dante and Virgil right after hell’s doors. The transition between the two subjects could represent the crossing of the River Styx.

The second subject contained in the introduction, repeated in B major, could recall the episode of Capaneo (Canto XIV). The motif identified with the descent of Dante and Virgil also appears. After reaching a great climax, we return to the slow opening, with a revival of the theme linked to Leave all hope by the brass, accompanied by the drum-roll motif. Once again Liszt here inscribes the score with the corresponding words of the Inferno.

The Second Circle of Hell: Paolo and Francesca

Dante and Virgil move deeper into hell. The infernal wind that eternally buffets the damned is represented by ascending and descending chromatic scales of strings and flutes.

This is followed by a 5/4 Almost Andante ma sempre un poco mosso: it begins with harp’s glissandos, with strings and woods in chromatic figurations, again recalling the wind.

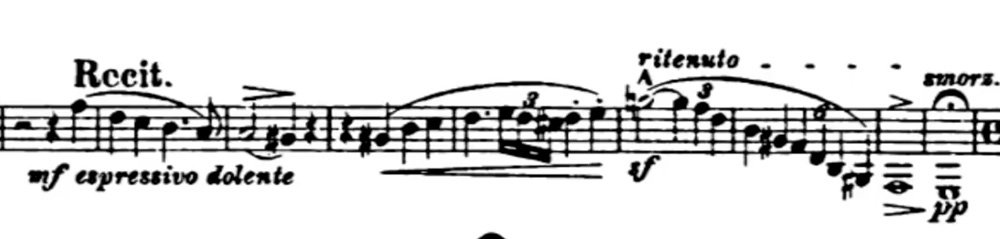

After a pause, the bass clarinet plays an expressive recitave, descending into the lowest range of the instrument:

The same theme is taken up and expanded by a pair of clarinets accompanied by the harp and the chromatic figures heard at the beginning of the section.

The explicit reference is to the Dante episode of Paolo and Francesca. Francesca da Rimini was forced into a political marriage with Giovanni Malatesta but fell in love with his younger brother Paolo. The affair was discovered by Giovanni, who killed them both.

Dante meets them in the circle of hell reserved for the lustful. Here, the couple is trapped in an eternal whirlwind, doomed to be forever swept through the air just as they allowed themselves to be swept away by their passions.

Although, when Dante hears Francesca’s story he is so struck by it that he faints out of pity.

…. Nessun maggior dolore

che ricordarsi del tempo felice

ne la miseria.

…. There is no greater sorrow

Than to recall happy times

In the midst of misery.

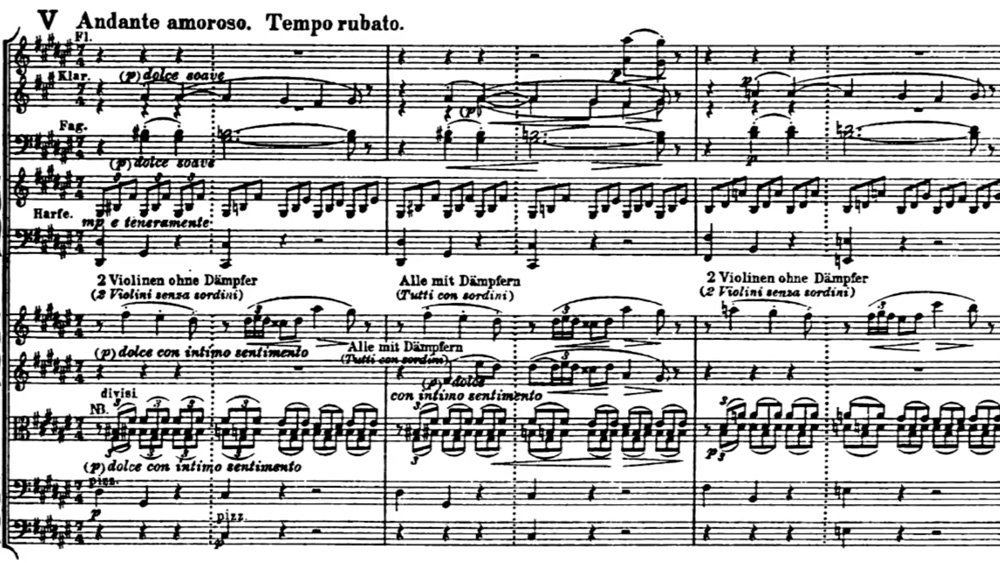

After a short passage based on a theme derived from the recitative, an Andante amoroso of a passionate theme in 7/4 follows.

Both the orchestration and harmony are curious: Liszt creates a dialogue between all the violins, muted, and a couple of violins, unmuted. And the key signature suggests an F# major, a key that Liszt associates with the divine. But the theme actually begins in D# minor, a very odd tonality, and moves to F♯ minor and A minor.

The Seventh Circle of Hell

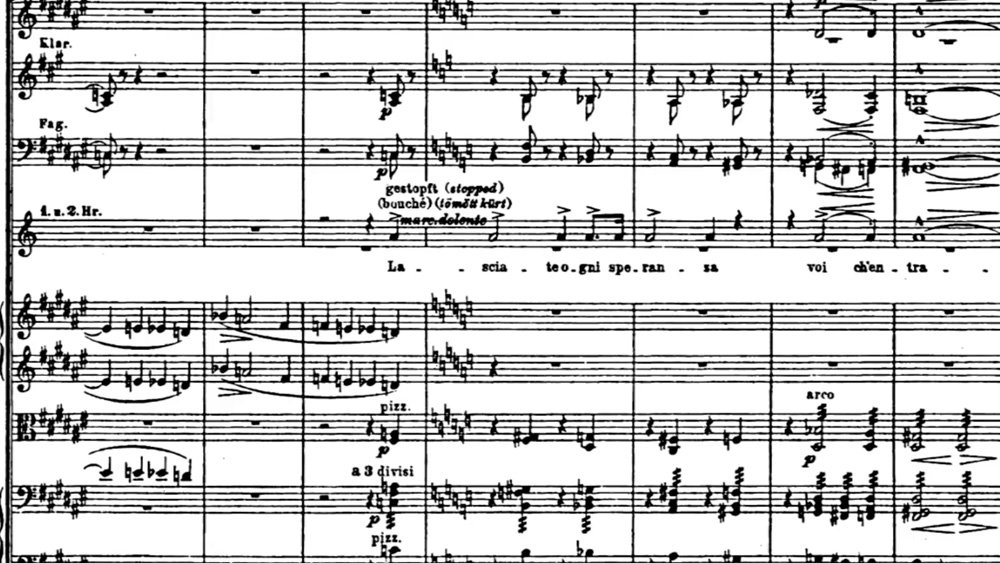

We transition to the 7th circle through a return of the Lasciate ogni speranza theme.

A short cadenza for harp, which continues the infernal wind motif, leads to a passage about which Liszt wrote: “The whole passage is intended to be a blasphemous mocking laughter” probably with a reference to the character of Capaneo. The dominant motifs are repetitions of passages already heard previously.

The time signature reverts to Alla breve, the key signature is canceled, and the tempo quickens to Tempo primo in preparation for the recapitulation.

Recapitulation and coda

After a recapitulation that perhaps represents the eighth and ninth circles – in which the first subject is recalled by augmentation, the tempo accelerates to a climax, and the second subject is repeated with little change – another climax leads to the coda, dominated by the second subject and the descent motif; the latter leads to an even more intense climax: (molto fortissimo). In the last ten bars, the motif Lasciate ogni speranza returns while Dante and Virgil emerge from the opposite side of the world, at the feet of the mountain of Purgatory.

The movement ends in D, even if the ambiguous key is maintained until the last measure; the open fifth of the finale could represent the impotence of Lucifer who fell into the depths of hell.

Sandro Botticelli, Chart of Hell – between 1480 and 1490

0 Comments