Introduction

Written between 1908 and 1909, Das Lied is a succession of 6 songs, for 2 singers alternating movements.

In order to even get a glimpse into this monumental work, we need to understand the biographical background that nurtured it.

Mahler had been obsessed with death for a long time but in the last years of his life, it acquired a whole new meaning. In 1907 Mahler lost his daughter Maria to scarlet fever. Soon after her death, Mahler himself was diagnosed with a congenital heart malfunction that would prohibit any activities that would exhaust his heart.

If that wasn’t enough, a long-lasting antisemitic campaign against his role as director of the then Vienna Hofoper had gotten the best of him, resulting in his resignation.

Gustav Mahler in 1909

As he wrote to Bruno Walter:

“With one stroke I have lost everything I have gained in terms of who I thought I was, and have to learn my first steps again like a newborn”

Das Lied von der Erde: the inspiration

In his quest for answers or, simply, solace Mahler was captivated by something extraneous: Hans Bethge’s Die chinesische Flöte, a paraphrase of an anthology of Chinese poetry published first in a German translation by Hans Heilmann in 1905.

Heilman himself had based his work on 2 French translations that had appeared in the 1860s: Poésies de l’époque des Thang (1862) by the Marquis d’Hervey-Saint-Deny and Livre de Jade (1867) by Judith Gautier.

Each movement of Das Lied von der Erde sets one poem, with the exception of the last movement, which combines two. Mahler chose seven poems reflecting, in Chinese philosophy, the concept of transcendence: a way of going beyond the ordinary, valuing the spiritual aspects of life over the material ones. This concept ties organically with the appreciation and identification with nature, a theme that had always been so dear to Mahler.

Mahler was looking for answers and he explored the combination of the nature subject – something touchable and down to earth – with a philosophical one – something more intellectual without venturing into religion – in a unique spiritual synthesis.

From a technical point of view, the most difficult thing to do is the independence of the two hands. You will find that in Mahler, more than in any other composer, this is fundamental. There’s too much to keep track of, too many contrasting lines, where, for example, often one part plays a diminuendo while another plays a crescendo.

For a full technical analysis, look up the video in the repertoire section

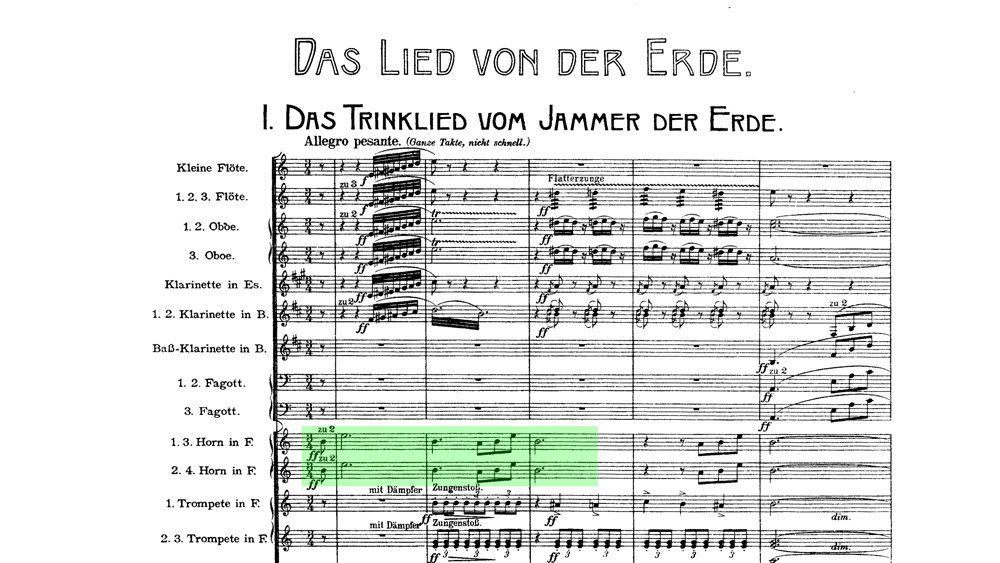

Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde

Should you need a score you can find one here.

The tone of the symphony is set right from the opening piece titled “The drinking song of earth’s sorrow“. It’s a rather pessimistic reflection upon life, summarized in the verse “Dunkel ist das Leben, ist der Tod” – “Dark is life, and so is death.”

Mahler opens the work with a dramatic gesture, a 16 bars introduction in A minor. This theme, played here by 4 horns, will reappear times and again throughout the movement

Wine is coming but the speaker urges the audience to wait until he’s sung them his song.

Mahler moves swiftly from A minor to Bb major, back to A minor, then A major, A minor, Bb major, and G minor. This constant harmonic fluidity makes it quite difficult to identify different sections based on the harmonic analysis. The thematic material, however, is of great help in this.

This introduction by the speaker, outlined in the first stanza of the poem, holds all the pessimism we would expect:

“The song of sorrow shall

resound in gusts of

laughter through your soul.

When sorrow draws near,

the gardens of the soul lie wasted,

Joy and song wither and die.

Dark is life, and so is death.”

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Der Einsame im Herbst

From the rollercoaster of the first movement, we land in a totally different atmosphere. Look at the descriptiveness of the tempo indication: Somewhat dragging. Exhausted.

“The lonely one in autumn” is a lament for the dying of the flowers and the passing of beauty. It’s a return to the theme of nature, combined with the theme of time.

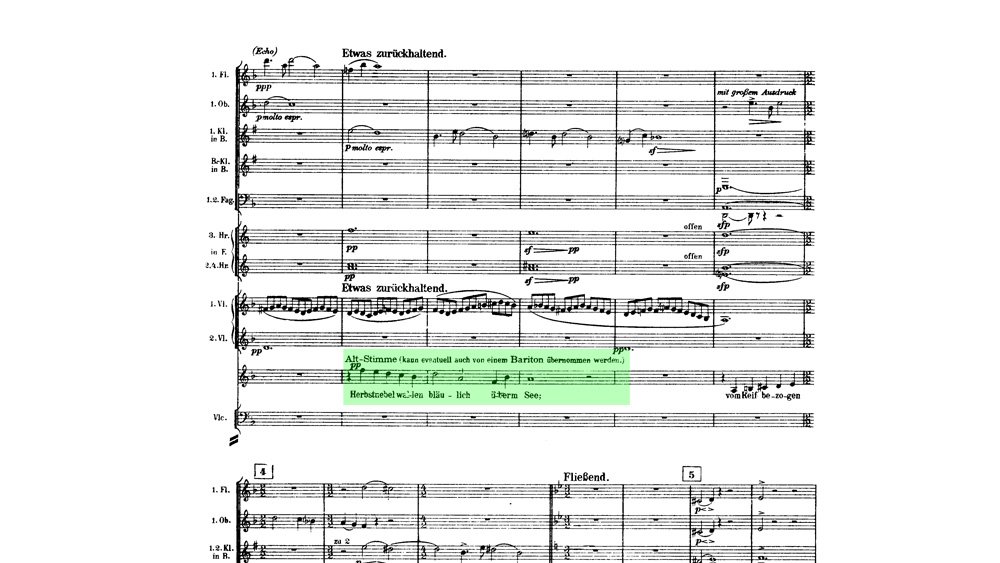

Mahler made a significant change to the text: the original article was Die, the feminine one. He changed it to Der, changing the gender of the speaker from a woman to a man. It’s a difference in culture: while it was not uncommon in Chinese poetry to have a female speaker, Mahler was more accustomed to have a male speaker. However, he did recognize the sensitive aspect of the text and set it for an alto voice, with the option of being performed by a baritone as well.

The movement starts and ends in D minor without modulating to far keys like the first movement. Everything contributes to a sense of calmness. Again, we have 4 stanzas, each one connected to the other by an interlude.

The opening couldn’t be more lonely: only the first violins, with mutes, are playing a wavy but still repeating figure of 8th notes.

Two bars later a solo oboe comes in. The theme played by the oboe seems to fold upon itself, trying to figure out its own direction. The texture grows, almost imperceptibly. Two horns and the second violins first join in in thirds with the first and then a clarinet echoes the oboe.

One by one the other instruments are added to the mix: a second clarinet, the bass clarinet, the violas, cellos, and a flute. But the sound remains clear without the sensation of a crescendo built by the overlapping of the instruments. As a matter of fact, some come in, some leave, in a sort of chamber music game.

All of this prepares the entrance of the alto (or the baritone).

It’s the autumn mists, drifting over the lake with a downward movement. It is the world observed from the outside. The orchestration hints towards an almost cold and careless mood but the movements of the singer’s line betray a deeper emotion.

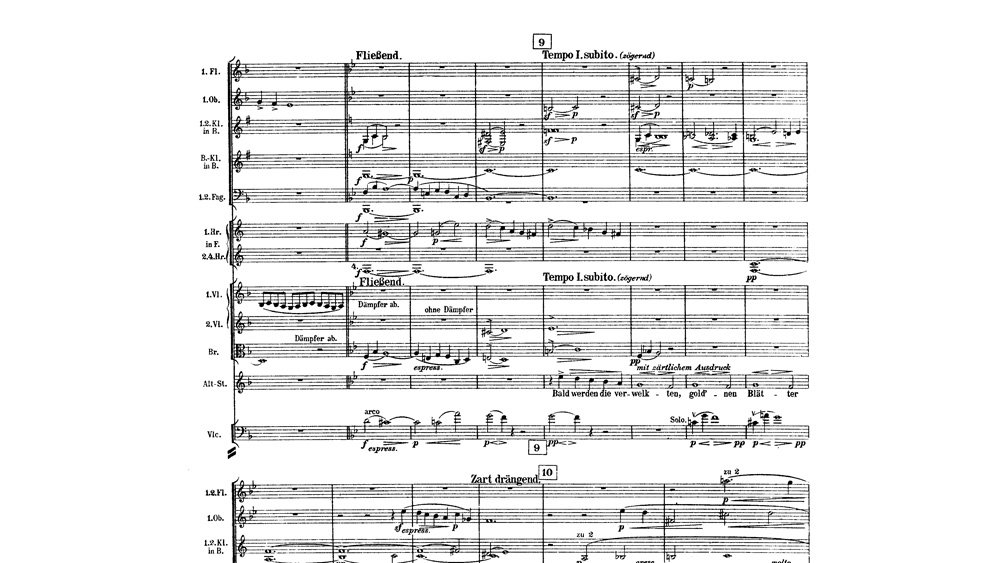

At the Fliessend the singer rests, giving the line to the horn and cellos.

A few bars and the speaker is back to complete the first stanza. An element of importance, which we find throughout the whole movement, is the cello line at the Tempo I

This rocking figure, with duplets nested into triplets, is mesmerizing, rendering the almost hypnotic state of the speaker in contemplation of the world. The speaker’s line moves, again downward and upward, followed by a short interlude connecting to the second stanza.

The formula is repeated but there seems to be an increase in tension. It’s just a moment. Look at the triplets of the strings: they intend to raise the temperature but they are forced back down turning into the rocking movement

At rehearsal 11 Mahler lets us look inside his own self: “Mein Herz ist müde” – My heart is tired. 3 heartbeats followed by 2 longer ones. And yet, look at what he writes on top of that line: Ohne Ausdruck, without expression.

Followed by an attempt to fight it: the scale of the violins ends on a reverse motive which will determine the very end of the symphony.

We’ll see a lot more of this motive on the way: in the last movement is sung on the word “ewig“, forever.

The flute dampens that thought right away, the rocking motive returns, and right after the speaker is ready to continue: “My little lamp has burnt out with a splutter“, yearning for some rest and consolation

And just like that we circle back to the beginning. The 4th stanza makes use of the same material, with a different orchestration. The bassoon adds an ever sadder note, sounding remote and untouchable

“Der Herbst in meinem Herzen

währt zu lange.” – Autumn in my heart is lasting

too long.

We expect everything to die away. But unexpectedly, we get to a fortissimo, which retreats within a bar, and then the music grows, drawing energy from 3 words in the following verse: Sun, love, shine

“Sun of love, will you never

shine again”

It builds and builds and for a few bars, we have some sort of hope. The hope is slowly crushed as we realize that there is no hope. We are taken back to the opening material. We are doomed to observe the inevitability of time, consuming everything, and everyone. Look at the last notes of the violins. It’s the “ewig” motive.

0 Comments