Introduction

In January 1861 Verdi – who hadn’t worked on a new opera for 2 years (his last opera, “Un ballo in maschera” is from 1859) – was still debating whether or not accepting to be a candidate to the first Italian parliament. In the same period he received an offer from the St. Petersburg theater to compose a new opera for the following season.

He debated on the subject for some time but eventually opted for the Spanish drama Don Alvaro, o La fuerza del sino by Angel de Saavedra y Ramirez. As Verdi himself wrote to his French editor, La forza del destino is a “big and powerful drama, and I’m really in love with it“. He started writing in September and was done with it by December.

As smoothly as things went in the early stages, this opera is known to have had troubles since its first staging: the primadonna, for whom Verdi had written the role, was indisposed and they could not find a replacement, being forced to postpone the premiere; the Spanish premiere was partially cut by the censorship; on top of it, Verdi had quite a few doubts, as it seemed like the audience was put off by the number of deaths throughout the opera.

As a curiosity, with the years this opera acquired the weird fame of bringing bad luck. Musicians in the pit and on stage always kid around about it.

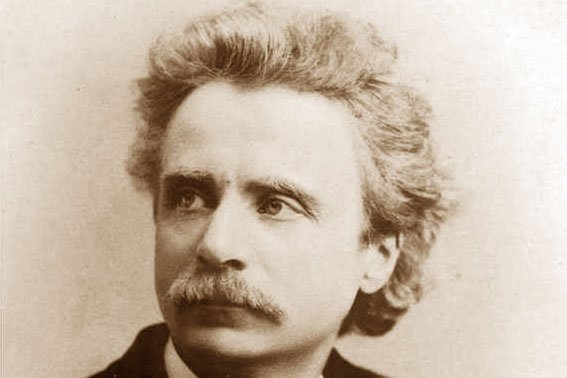

Giuseppe Verdi painted by Giovanni Boldini

Giuseppe Verdi – An analysis of the Ouverture from La forza del destino

In case you don’t have it at hand, here’s a quick link to the score.

The opening Sinfonia was added by Verdi in 1869 with the idea of an opening piece but also of a standalone work. The Sinfonia starts with 3 calling chords. Calling as in calling for the attention of the audience.

At this point in time, theaters’ lights were still staying on and people were chatting, eating, and generally enjoying themselves. Aside from the dramatic purposes of introducing us to the subject of the opera, these chords were also telling the audience that the show was about to start.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Technical tip

The beginning of this phrase requires a pulseless preparation, just like the beginning of Beethoven’s 5th symphony. Move your hand up in tempo but pulse only on the downbeat. This will ensure clarity for everyone.

For a full technical analysis, look up the video in the repertoire section

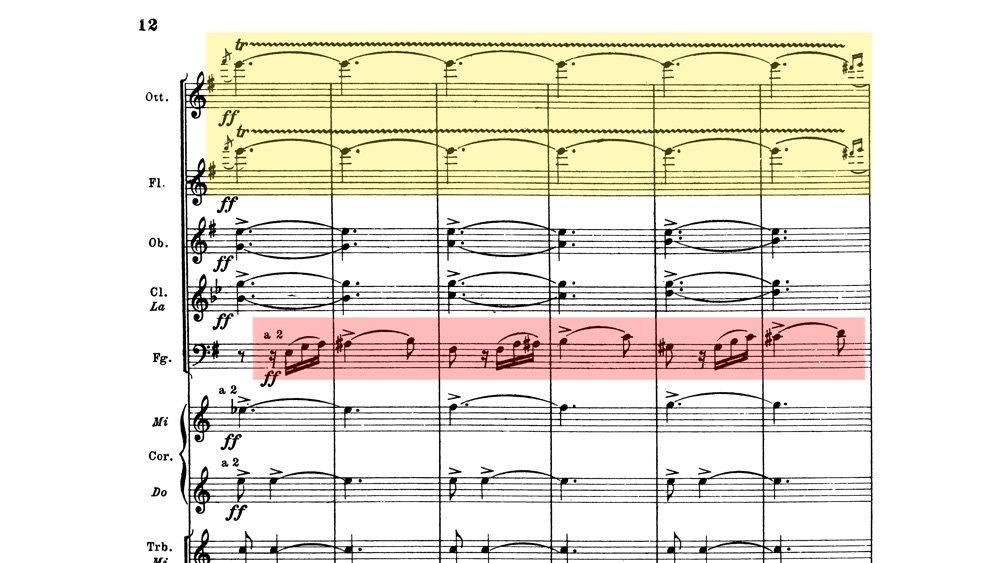

You can notice right away how dark of a color Verdi is asking for: the strings play in their low register; the main line is played by the violins in octave with the cellos; the accompaniment is left to the violas, double basses, bassoons, and all 3 trombones. On bars 12 and 13 the darkness is emphasized by the doubling of the line in the clarinets.

The tempo marking, Allegro agitato e presto (agitated and quick), renders the idea of agitation, of energy and nervousness.

At the end of the first phrase, the head of the idea is retaken and used in a 2-bars model. Notice a couple of things here: the same 3 notes we hear in the violins are echoed in reverse in the bass line; the horns add the dominant on an off beat, increasing the anxiety of the passage

The phrase is repeated and ends up on a suspension. A full bar of silence, used to create anticipation in the listener, allowing for total quiet before the next musical idea. Until now, we’ve been navigating in the waters of E minor and A minor.

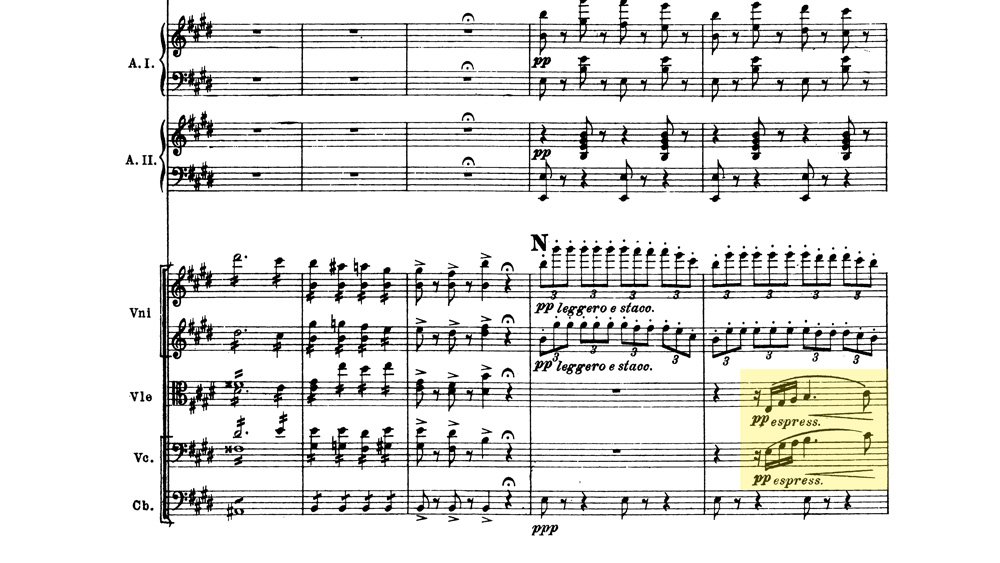

Verdi now turns to G major. The theme is played in triple piano by the violins in octaves accompanied by tremolos of the violas. Nobody else. The combination of the key change and a light orchestration make for a very airy effect

On the fourth bar, the main theme returns again, interjecting the melody, and serving, once more, as a connector between the different sections

This very same idea becomes an accompaniment throughout this entire section. But it’s not just a mere accompaniment: despite the major key, the anxiety of the figure remains, telling us that even though what we hear in the foreground is serene, this atmosphere is not meant to last.

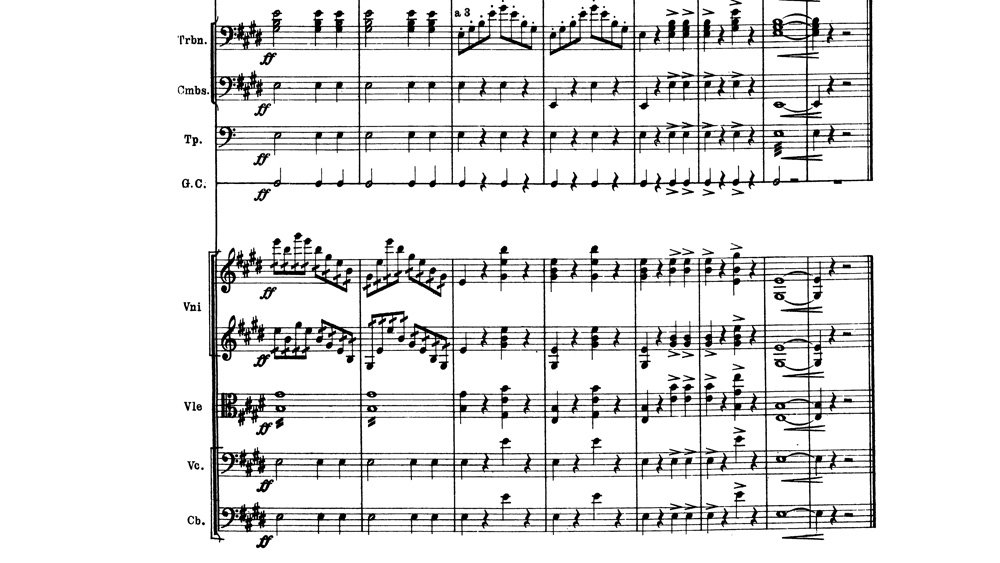

The phrase is repeated, growing with the addition of the trombones, the woodwinds, horns, and timpani, and finally a solo trumpet, and the tuba. Everybody is playing piano, or pianissimo or triple piano; but by stacking section after section one on top of the other Verdi creates a natural crescendo. This gets emphasized in the last 2 bars before another tempo change by a written crescendo, exploding in a Presto come prima (Presto as before).

And here we go again: the head of the first theme is back in full blown, played in the upper register and answered in the lower

The fury increases: the violins climb higher and higher, flute and piccolo scream out with their trills while all the bass lines – bassoons, trombones, tuba, cellos, and basses – ride the head of the theme

And a new idea makes its way in. It’s a lovely and cheerful theme, played by the clarinet, accompanied by 2 harps and a pizzicato of the cellos

The orchestration slightly thickens and we end up on a dramatic section once again. The trumpets, along with the horns and the trombones, play a typically battle-call figure. The fire underneath is provided by a figure derived from the head of the first theme once again. First and second violins tail each other, with those same 3 16th notes appearing over and over again. And these 16th are turned into 8th notes in the lower register

Technical tip

Conduct this chorale with small gestures, at eye level: you will get a warm and round sound. Save your left or right hand for the strings entrance, with a sharp pulse on the downbeat followed by a bit of registration.

For a full technical analysis, look up the video in the repertoire section

You may think we’re finished now, but Verdi has one more surprise: our first theme is back, in E major played by the bassoons, violas, and cellos. But the accompaniment is a dancing counterline in triplets played by the first and second violins. Everything is now seen in a new light and a happier atmosphere

Even when the brass enter with offbeat accents at letter O the conflict is resolved right away, landing again on E major. The energy rises, the excitement grows in this coda reaching the Più’ animato

and closing in a grandiose way

In conclusion

The ouverture of the opera remains one of the most engaging pieces in the repertoire: it certainly appeals to the audience but it’s incredibly fun to play for the orchestra and offers countless opportunities for a conductor to showcase musicality and technique.

0 Comments