Introduction

Between 1809 and 1810, Beethoven wrote a set of incidental music pieces to the 1787 play titled Egmont by Wolfgang Goethe. The first performance was given on June 15th, 1810 in Vienna.

The subject takes after the life of 16th-century nobleman Lamoraal, Count of Egmont from the Low Countries also known as Habsburg Netherlands. The heroism of the character perfectly fitted Beethoven’s political views, as much as another character of a previous overture, Coriolan.

Beethoven had notoriously expressed his great outrage over Napoleon’s decision to crown himself Emperor in 1804, furiously scratching out his name in the dedication of his 3rd symphony, the Eroica. Egmont is yet another expression of his political concerns, giving Beethoven a good excuse to exalt the sacrifice of a man condemned to death for having stood up against oppression. Incidentally, the Overture became an unofficial anthem of the 1956 Hungarian revolution.

Joseph Karl Stieler: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at age 79

While the incidental music written by Beethoven sums up to 10 numbers, the overture remains the most popular one to this day.

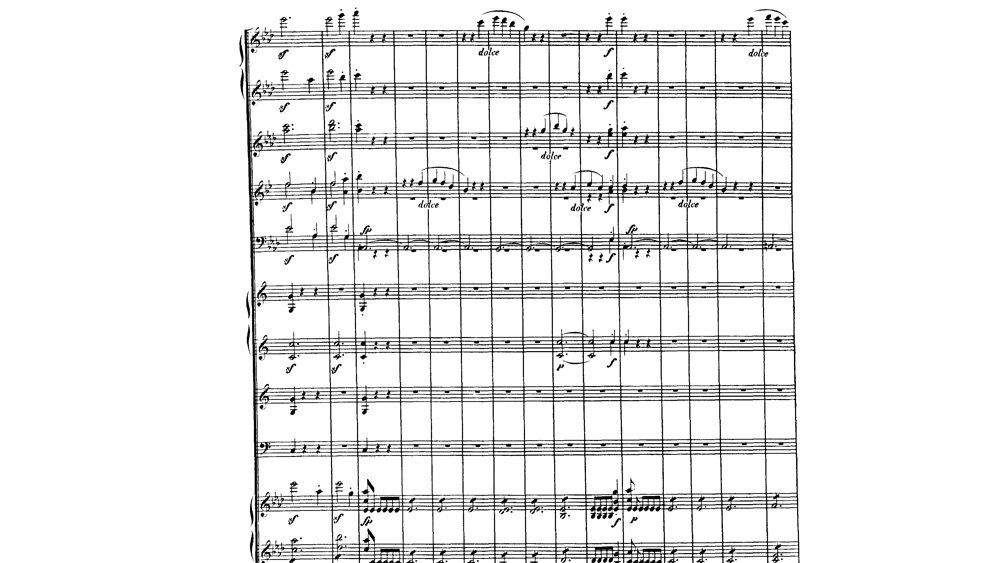

It’s written in sonata form: a form typical of the classicism comprising an exposition with two contrasting themes, a development section where the musical material gets reworked in various ways, and a recapitulation; everything is often framed by a slow introduction and a coda.

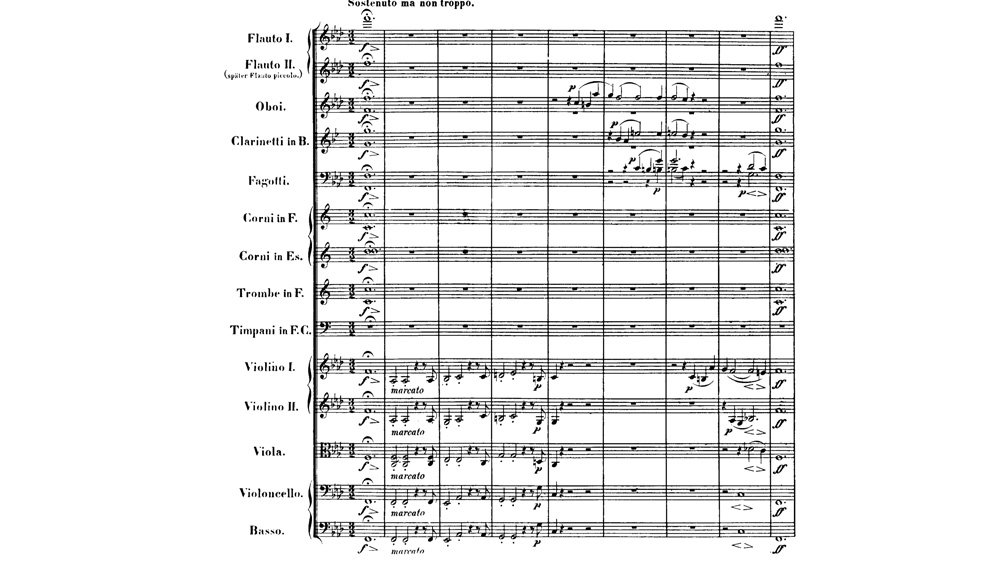

Sostenuto, ma non troppo

Should you need a score you can find one here.

Look at the opening, expressing all the drama of the character and the situation: one note, F, spread across the orchestra. No other pitches are played; it’s long, dramatic, in a forte dynamic.

The diminuendo goes into a second bar which is not less intense. Beethoven writes marcato underneath the strings, the only ones playing now. They are, again, very dramatic, in the low register, really heavy

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Allegro

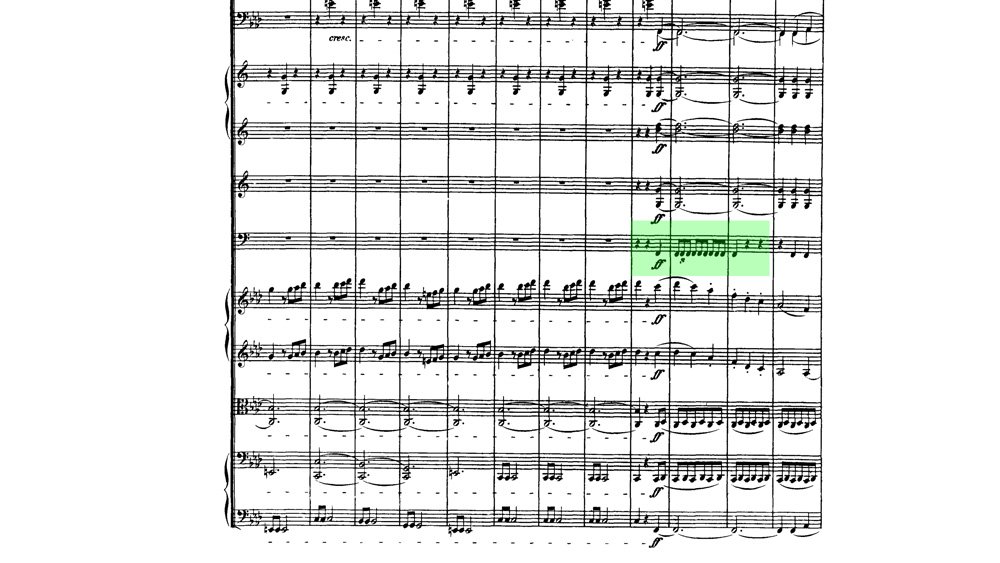

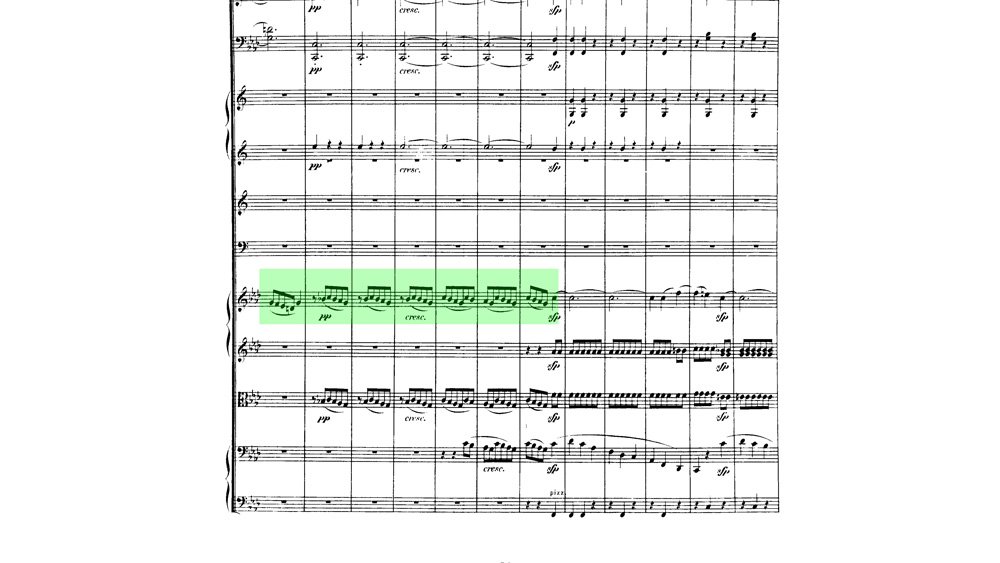

Once we get to the Allegro, the theme is not exposed right away: 4 bars are left in the hand of the first violins in octave with the cellos. They play against the natural accents of the bar: we moved to a ¾ meter but their musical accents fall every 2 beats. This creates a sense of urgency and instability. The theme follows the patterns and begins on a weak beat with a sforzando, played by the cellos

Technical tip

The transition into the Allegro is the trickiest spot of the overture: give a clear pulse on the first downbeat, let the players listen to each other, and keep out of the way. Less is more here.

For a full technical analysis, take a look at this other video

While the violins and woodwinds provide an answer, look at this cell in the cellos: it will shortly become essential

It appears, first, with an opposite motion, in the violins and violas; and then it’s used to build a huge crescendo towards the fortissimo. This music represents the fight between Count Egmont and the Spanish oppressors

Notice anything? This is the great ability that Beethoven has to take a single rhythmical cell and transform it over and over again, using it and reusing. It’s exactly the same rhythm of the first movement of his 5th symphony.

I want to point to another thing: look at the rhythm in the bass line in bars 42 and following. The same rhythm is present at bar 66. But more than that is reused in bar 74 in its reversed form.

Beethoven prepared us with the bass line first, and now gives us an element we are already familiar with to complete the transition to the second theme.

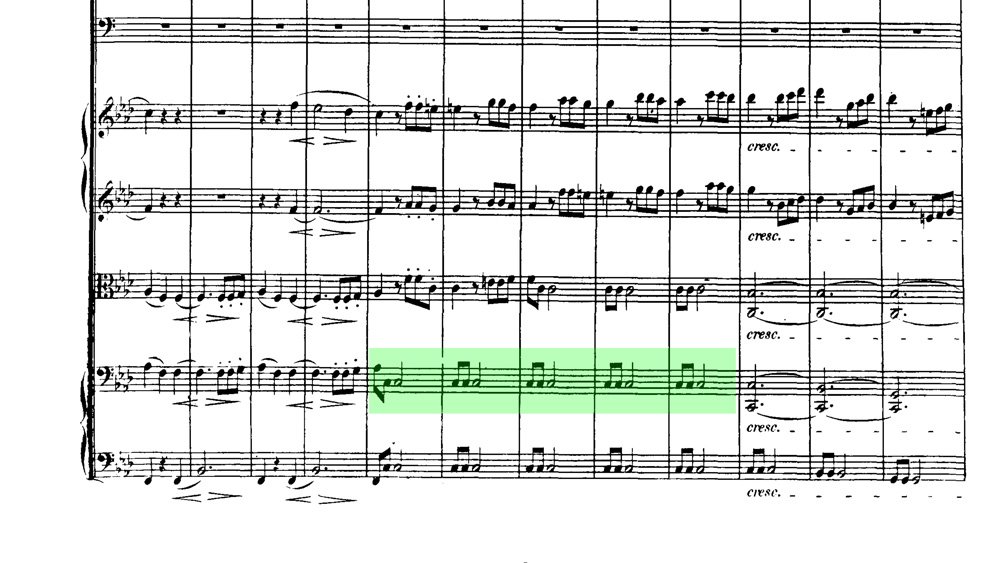

This is not our usual feminine second theme, as we heard, for instance in Coriolan. The woodwinds gently answer but the strings reiterate the fortissimo right after. We’re still in battle, with moves and countermoves, slashes, surprise attacks.

And the surprise continues with those rhythms coming in at the “wrong” time, again on the weak third beat of the bar.

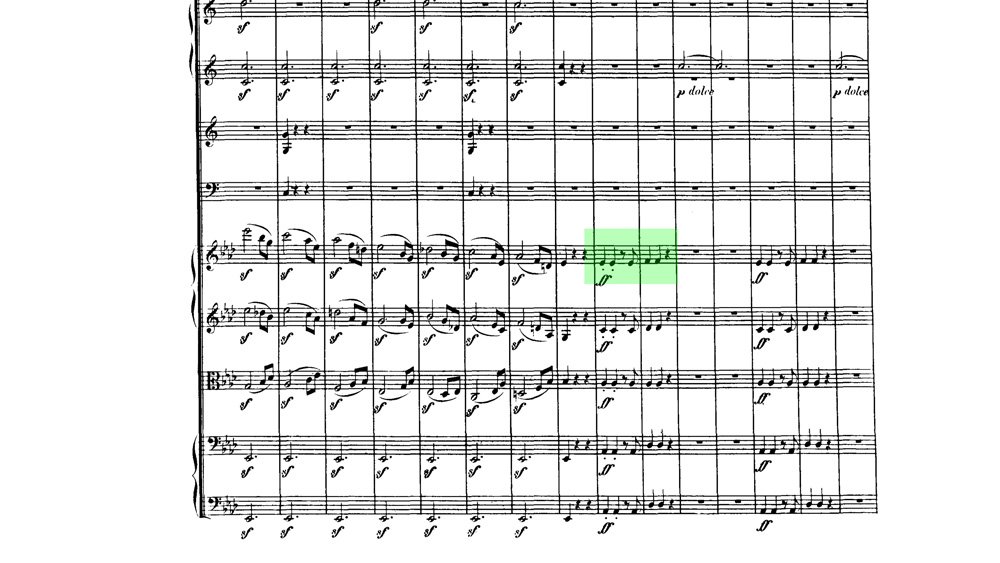

Notice how Beethoven just keeps going with alternating piano and dolce phrases with forte and powerful answers. There’s no time to rest, no time relax: as soon as we try to, he wakes us up with a slap on the face

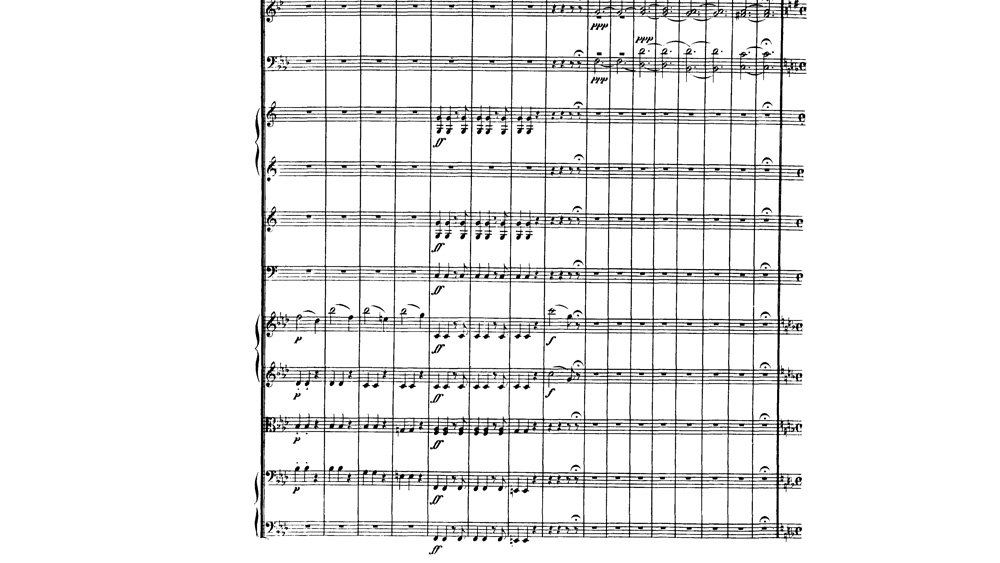

Except that, normally, the exposition of a movement in a minor key, in sonata form, ends on its relative major while the recapitulation ends on the minor key. But Beethoven has more surprises waiting for us: we end up, in fact, on a Db major.

Notice the use of the same material to create one more transition. Look at the violins on bar 278: they are “only” playing forte, not fortissimo anymore, and the G is an eight note, like a conversation that’s being all of a sudden cutoff.

Silence follows: Beethoven is anticipating the beheading of Count Egmont: as he noted in his sketches,

“death can be expressed by silence”

We end up in the coda: a glorious fanfare in honor of the hero. The pianissimo dynamic turns into a crescendo that swiftly takes us to the full force of the orchestra.

Bassoons, violas and cellos start on a motive counterpointed by the violins. Notice the sforzato markings on every single bar. The fiery battle ends with a final call from the trumpets and a typically military rhythm

0 Comments