Introduction

Referred to as ‘the father of the symphony’ Haydn was the first composer of the great trio of Viennese composers – the other two being Mozart and Beethoven – forming together the heart of the Classical period.

In 1791, the year in which Mozart died aged 35, Haydn was 59: he had just embarked in what would be the most successful decade of his career.

Haydn had spent much of his life as a court musician for the wealthy Esterházy family: when the old Prince Nikolaus died in the fall of 1790 Haydn became less tied to his duties at court.

Free to travel – as long as he introduced himself as “the Kapellmeister of Esterhàzy” – Haydn made extensive visits to London in 1791-1792 and 1794-1795.

And it was in London that he wrote his final 12 symphonies (nos. 93-104)

Portrait of Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1791

Royal College of Music Museum of Instruments

In London, Haydn was a celebrity: to the point where even the future King George IV (back then the Prince of Wales) had bowed to him.

The King and Queen tried to bribe him with a flat in Windsor in order to convince him to stay in London. Eventually, Haydn refused and went back to the Esterházy in 1795

Haydn Symphony n.104 “London”: an analysis of the 1st movement

Exposition

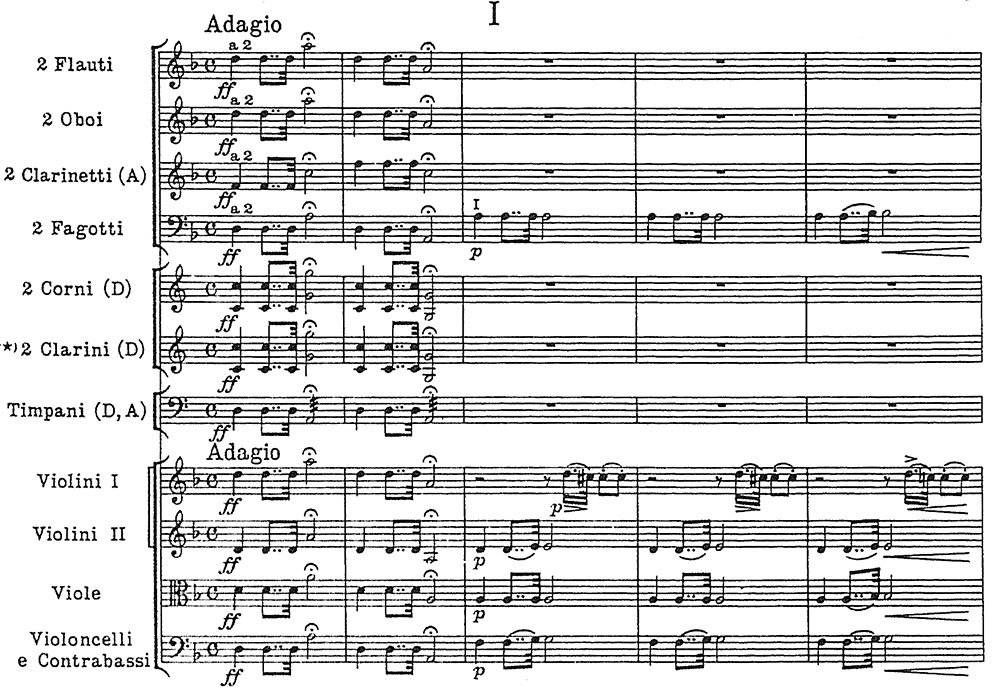

Adagio

In case you don’t have it at hand, here’s a quick link to the score.

The opening of the slow introduction carries a sense of expectation and grandeur. It’s a rhetorical gesture, with a fanfare-like character: tonic to dominant, dominant to tonic. We are clearly in D. But which one? Major or minor?

We know that for sure in the 3rd bar, with the F natural. Something similar happened in the opening of Mozart’s “Prague” Symphony, which we talked about in a previous episode. The sense of mystery continues: the dynamic drops to piano; the instrumentation is reduced to the strings and the bassoon; and instead of taking bold and assertive leaps, the music proceeds tentatively in smaller steps. But notice how the exact rhythm of the first 2 bars is repeated in the bass line

On bar number 5 we have the first change: the C# becomes a C natural, and the A (in the violas and bassoon) turns into a Bb. We’re moving to F major, the relative key of D minor

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

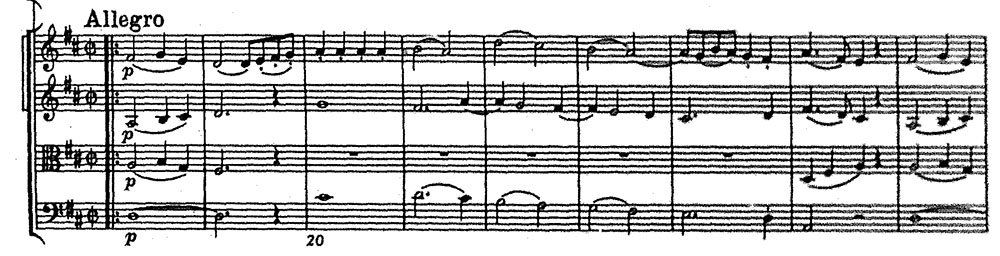

Allegro

First theme

All the mystery and minor passages in the introduction lead to a suspended dominant 7th chord on the A. Haydn has smartly set us up to not be sure, really, what to expect: will it be a minor or a major key? This is part of the surprise: the Allegro immediately changes the mood, which, given the suspense created in the introduction, sounds even brighter

This theme couldn’t get more classical in style: 16 bars split in half, with the first half of the phrase ending with an imperfect cadence and the second half with a perfect cadence, back on the tonic. And each 8-bars-cycle can be split in 4 and down to 2 bars: it’s the mathematical precision, the perfect balance within a phrase that was so typical of this era.

Notice also that the dynamic is piano: Haydn had already the full orchestra playing in a forte dynamic in the introduction, more than once: this change in dynamic increases the contrast between the introduction and the allegro, saving the tutti for later.

When it does come, the forte is exuberant and lively

Notice the construction of the phrase: 8 bars, formed by four 2-bars groups. And look at how Haydn ties up this tutti with the opening phrase: bars 17 and bar 32 share the same rhythm and the downward scale of bar 41 is the same as bars 21-22, just cut in half. The latter, by the way, is a composing technique called rhythmic diminution.

Haydn skillfully drives the phrase down

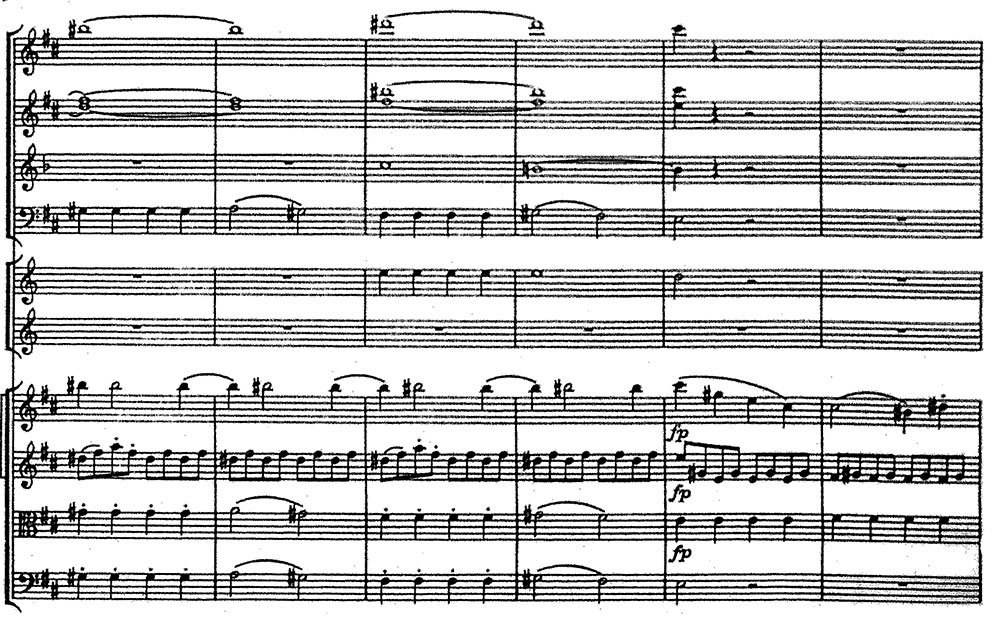

Again this is material we’ve already heard: the quarter note repetition, and the descending half-notes come straight from the opening phrase. Notice also the G# in bar 52, signifying the transition towards A major.

We take a break with an almost full bar of rest on measure 64, and then we land on the second theme

Second theme

Except, this is not a second theme as we’ve seen so far in the previous episodes. This symphony is still built on the sonata form: an exposition, a development, a recapitulation; with an introduction at the beginning and a coda at the end. The difference is that the first and the second theme are the same: it’s called monothematic sonata form. It’s something Haydn had used more than once.

The first theme is transposed into the dominant key

Haydn enriches it by making some harmonic changes, like in bar 67, and some imitative counterpoint, like in bars 73-74 with the oboe-first violins and the cellos.

The liveliness returns at the end of the phrase with a fizzy progression played by the strings joined by the rest of the orchestra on bar 86.

Given the lack of a contrasting second theme, Haydn decides to introduce some new material in the coda of the exposition, starting on bar 100. Haydn plays with the A major arpeggio in the flute and violins part and the next tutti ends the exposition with brilliance.

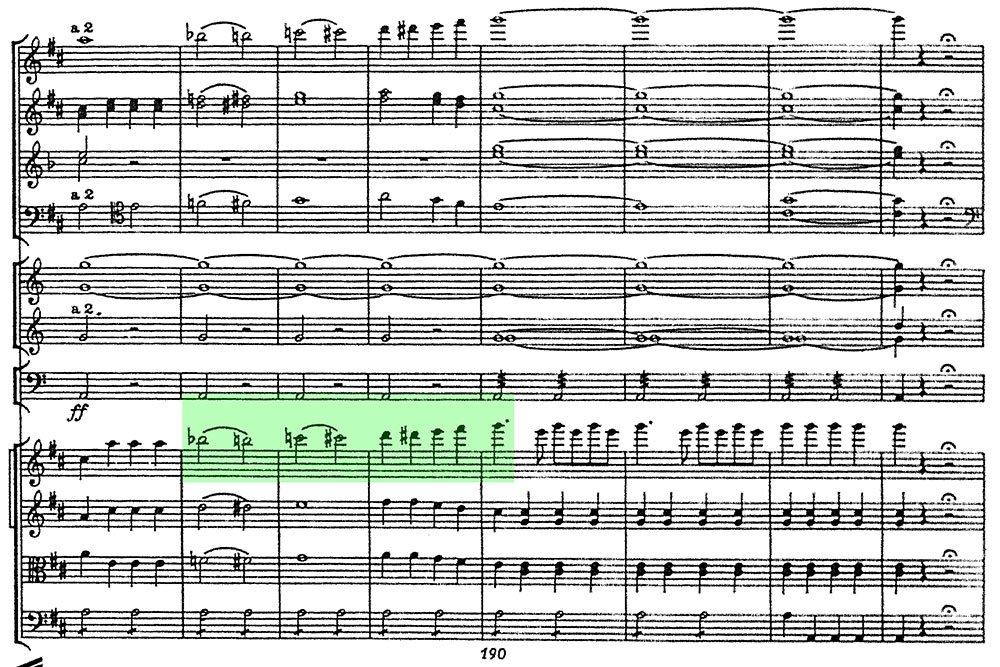

Development

The development takes us back to a sense of mystery: the rhythmic material is familiar but the harmony is rich in chromaticism and very unstable

The tutti drives the music to the remote key of C# minor on bar 145

Recapitulation and coda

The recap presents some differences compared to the exposition: the second part of the first theme is played by flute and oboes. Also, notice how the melodic line is given to the second oboe, below everyone else

Except for a few minor changes, the rest remains the same. Almost. Haydn knows that by now we’ve heard the first theme quite a few times. But there’s no second theme to get to. Instead of repeating the first theme again, he starts chopping it up, tentatively interrupting it with bars of silence

then plays with the different colors of the orchestra, with the head of the theme bouncing like a ball between oboes, violins, flute, bassoons, violas

till we get to the forte and end up on the codetta, balancing the recapitulation with the exposition. After this, we have a final coda, starting on bar 277 and the movement ends in a brisk way

In conclusion

Haydn is a clever composer, and his way of carrying the orchestra is not that predictable: for a conductor, it’s a real treat to look at all the white pearls hidden in the score. And even more to make them emerge without disturbing the perfect balance that the composer created.

0 Comments