Introduction

Considered by some as an early tone poem, Mendelssohn wrote this concert Ouverture in the early 1830s: it’s the musical transliteration of a journey Mendelssohn took in Scotland where he had visited the Hebrides islands, and specifically the island of Staffa, with its basalt sea cave known as Fingal’s Cave. As a concert overture, The Hebrides does not precede a play like, say, Beethoven’s Coriolan Ouverture, or an opera but is a standalone composition.

Mendelssohn’s The Hebrides: analysis

Exposition

Looking at the score, two main things call for attention:

The composing construct

Mendelssohn has the intuition of using overlapping chords to describe the rising of the tide: the violins begin on a F#, the clarinets overlap with an A, and the oboes play a C#. This chord is eluding the typical functional harmony. In a B minor, the key of the piece, we would expect maybe something like an E minor followed by a dominant 7th on the F#: a perfectly normal succession of chords that so much music of the time turns around (Mendelssohn’s included). Instead, here we go from a B minor to a D major to an F# minor, a sort of rising progression of chords eluding the tension and the expected resolution of the A#.

The development of a single cell

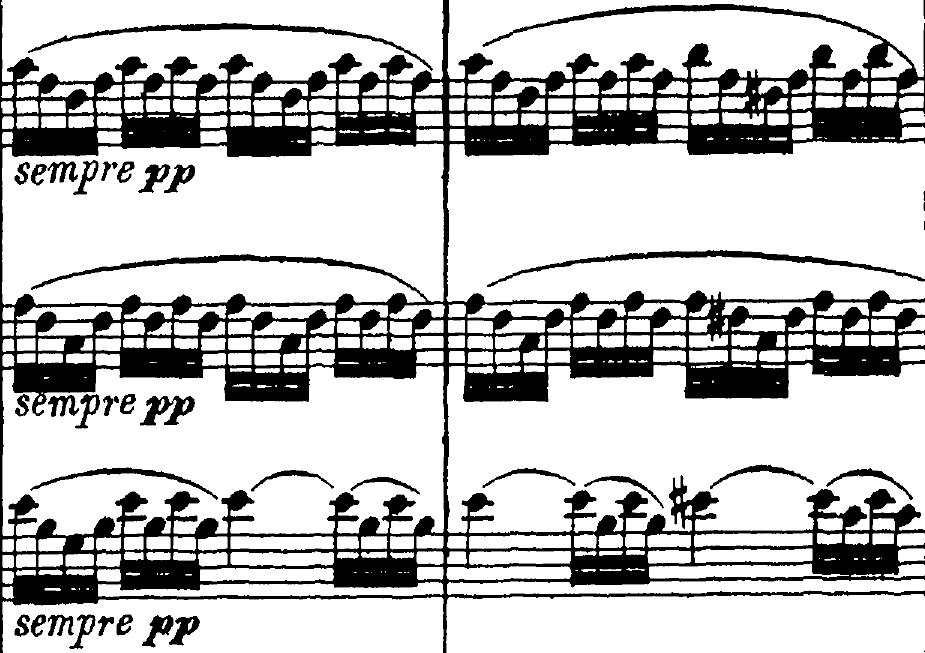

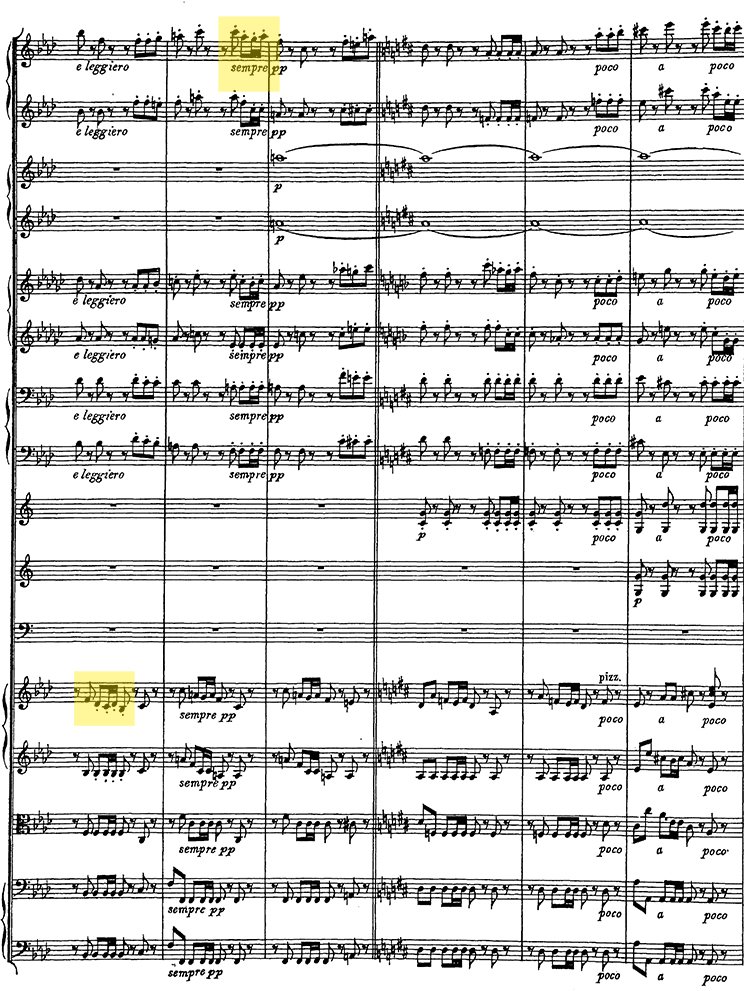

Almost the entire piece is derived from the first bar: violas, cellos, and bassoons play this motive

which is not an full long melody like Mendelssohn had written in other compositions. Following the chord progression, the motive rises, again and again. These few notes contain the thematic material for the whole Ouverture.

The compositional technique of The Hebrides is remarkably similar to Beethoven’s 6th symphony, in which the 1st movement spurs out of a motivic cell, while the chord progressions are used to raise the level of energy.

Take a look at the intervals: a descending third, a faster passage going down another third, and then a fourth. Mendelssohn reverts this structure to create the ascending answer to the motive.

The 2 faster notes form a fragment that is multiplied, generating waves that little by little become bigger and bigger: the rising figure of the 2nd violins on bar 16 for example, answering to the descending figure of the 1st violins in the first half of the same bar.

Notice how much the dynamics play in the overall arch of the phrasing, adding to the sensation of the movement of the waves, going from pianissimo to fortissimo within the span of a couple of bars.

Technical tip

On bar 27 1st flute, 1st oboe, and 1st bassoon do not share the same dynamics with the rest of the orchestra and their sforzando is still within a mezzoforte sonority at maximum. Make sure the crescendos and diminuendos of the other sections are contained.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Second theme

The second theme of The Hebrides comes rising out of the first one, played by the cellos and bassoons, and again it goes up and down, just like the tide:

Notice how the violins and violas color this line with their figures (also in thirds and fourths, just like the opening of the first theme), almost like sprinkles of water or like the sun rays reflecting on the water. These figures are then played by the lower strings, once the violins take on the theme.

Technical tip

On bar 43 register the line of the clarinet and bassoon with one hand and save your other hand for the trumpets on bar 45. If the cellos are seating next to the 1st violins, for example, you can use your left hand for the woodwinds which, by registering the line, will be perfectly positioned to make a connection with the cellos on the entrance of the second theme. This will also give you room to register the cello line upwards.

This second theme is tied to the first by its intervals

Subsequently, we get to a suspended moment where we hear clearly the first motive, accumulating energy that explodes into the end of the exposition. The coda, again, comes from the first motive, contracted in a faster version.

Development

Trumpets and horns introduce the development through a calling sound (again in intervals of thirds and fourths) followed by the woodwinds in an interval of a fourth, interjected by the full first motive. It’s almost like hearing the ships around the Hebrides islands. These “calls” are unattached from one another, heard in the distance from the Fingal’s cave.

This distance creates a perfect terrain for the appearance of the second theme which comes in soothing, filling the gaps with the warmth of the cellos, followed by the violins.

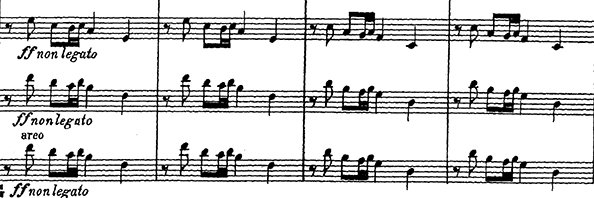

The energy level changes, moving to the very far key of F minor, like a ship that’s been taken off course for some time. The same tide brings us back to the home key, where the motive is transformed from lyrical to rhythmic, bouncing back and forth between strings and woodwinds:

Technical tip

In order to help the ensemble, keep your strokes tight, small, and sharp, just pulsing with your wrist with a very short rebound.

The climax comes with a storming of descending and rising scales that slowly but inevitably takes back to the recapitulation.

Technical tip

On the 3rd beat of bar 176 mark the timpani entrance: it will guarantee the woodwinds and brass coming out of the tied note together.

Recapitulation

Everything looks just like the beginning but, in fact, the structure is shortened, and we are rapidly taken to the second theme, played this time by a melancholic clarinet marked tranquillo assai (very tranquil).

It’s a peaceful moment, but the energy accumulated during the development hasn’t had time to dissipate yet and breaks in through the violins with the Animato on 217. The waves rise and drop through short frantic scales while the first motive comes back, hurled from one section to the other.

Notice how the first motive on bar 226 is specifically marked as non legato.

The ships’ calling comes back marking the end of the coda where we finally rest, going through fragments of the 1st and 2nd motives: an echo of the 1st motive, played by the clarinet, is interrupted by the harsh chords of the rest of the orchestra while a solo flute plays the last ascending wave, which remains almost suspended in the air, finding its closure in the low pizzicatos of the strings doubled by the timpani.

In conclusion

Mendelssohn’s inventiveness and crafts are legendary: apparently, he sketched down the first few bars of The Hebrides while still being in the Fingal’s cave. For a conductor, this is a really fun piece to perform, though its apparent ease can be somewhat of a trap, as it often happens with Mendelssohn’s music. I personally find the changes in dynamics and the ascending/descending lines to be perfect spots for registration and fluidity of gestures. Just like the waves 🙂

0 Comments