Introduction

Inspired by the novel by Antoine François Prévost “History of the Chevalier Des Grieux and Manon Lescaut” (1731), the opera was composed between the summer of 1889 and October 1892. To lengthen the time of composition was above all the difficult gestation of a libretto that passed into the hands of many writers – in particular Marco Praga, Domenico Oliva, Giuseppe Giacosa, and Luigi Illica. Ruggero Leoncavallo (the very same composer with whom Puccini would have a querelle a few years later about his next opera, La Bohème).

This whirlwind of librettists shows, in the final analysis, how the only true “author” of Manon Lescaut was Puccini, who among other things changed the initial dramaturgical plan by eliminating one act completely. Puccini’s sense of theater was one of the things that drove his librettists crazy. But it was also key to the success of his operas.

Manon’s costume for Act II of Manon Lescaut by Adolf Hohenstein for the world premiere performance, Teatro Regio di Torino, 1 February 1893

The adventure of Manon Lescaut began a few months after Edgar‘s debut, on April 21, 1889, whose partial failure was attributed by everyone to the weakness of Ferdinando Fontana’s libretto.

In this period Puccini was engaged on three fronts: the remake of Edgar, the composition of the new opera, for now destined for the Teatro alla Scala, and the reduction of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg commissioned by Ricordi, to realize which he went to listen to Wagner’s opera in Bayreuth.

Des Grieux’s costume for Act II of Manon Lescaut by Adolf Hohenstein for the world premiere performance, Teatro Regio di Torino, 1 February 1893,

Puccini took some musical elements in Manon Lescaut from earlier works he had written. For example, the madrigal Sulla vetta tu del monte from act 2 echoes the Agnus Dei from his 1880 Messa a quattro voci. Other elements of Manon Lescaut come from his compositions for strings: the quartet Crisantemi, written for the death of Amedeo of Savoy in January 1890, became an integral part of the last act; and the love theme comes from the aria Mentia l’avviso of 1883.

The famous love duet between Manon and Des Grieux forms the basis for the intermezzo opening the third act, which became one of Puccini’s most popular symphonic frescoes.

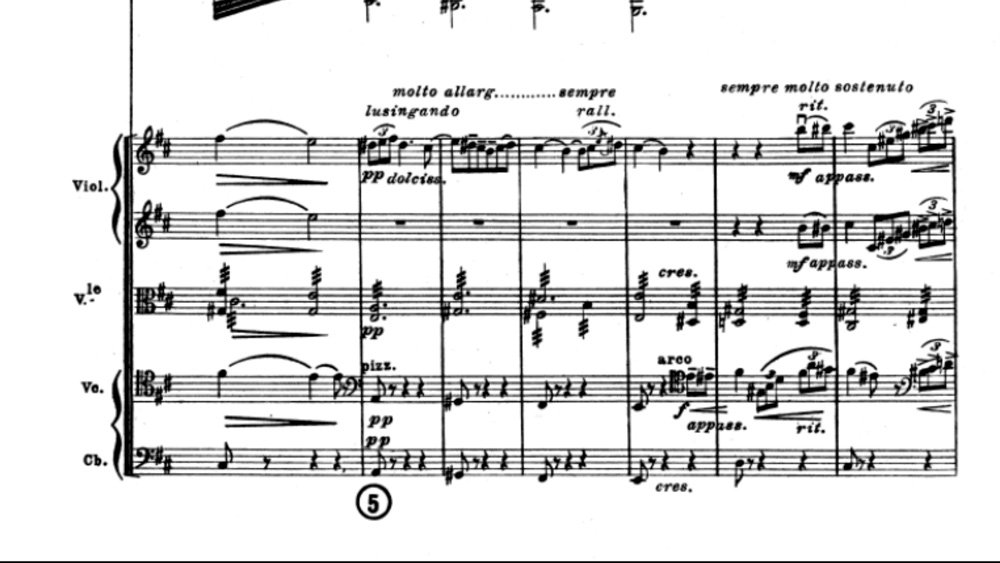

Lento espressivo

Should you need a score you can find one here.

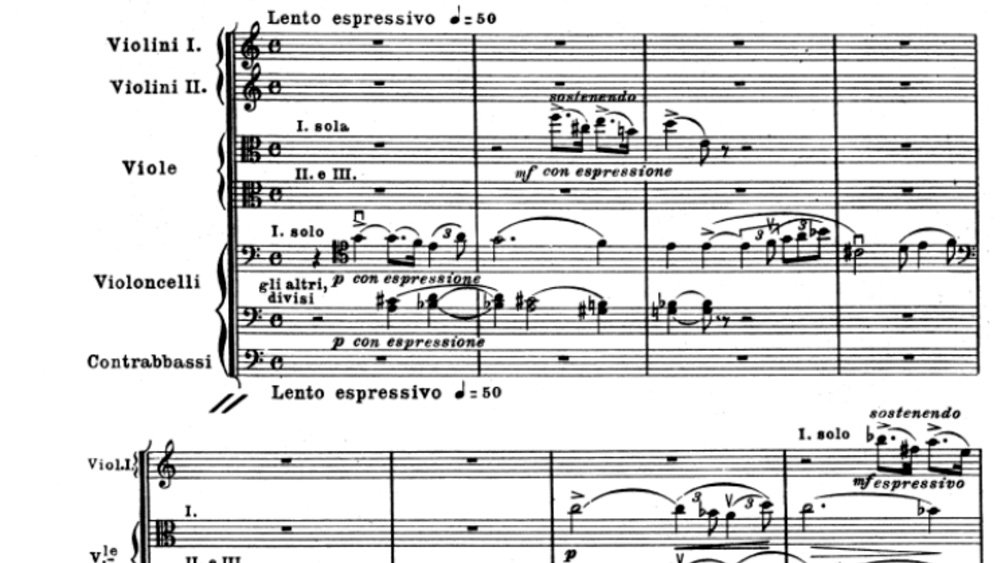

The color of the piece is clear from the few introductory bars of the Lento espressivo: violas and cellos divisi, plus a solo violin for a couple of bars.

The atmosphere is mysterious, dark, made unstable by chromaticism. Everything is enriched by a large number of indications in the score: con espressione, sostenendo, espressivo, plus a plethora of crescendo and diminuendo. This is all part of Puccini’s composing fingerprints: push and pull, huge leaps of expressivity, and the art of rubato.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Andante calmo

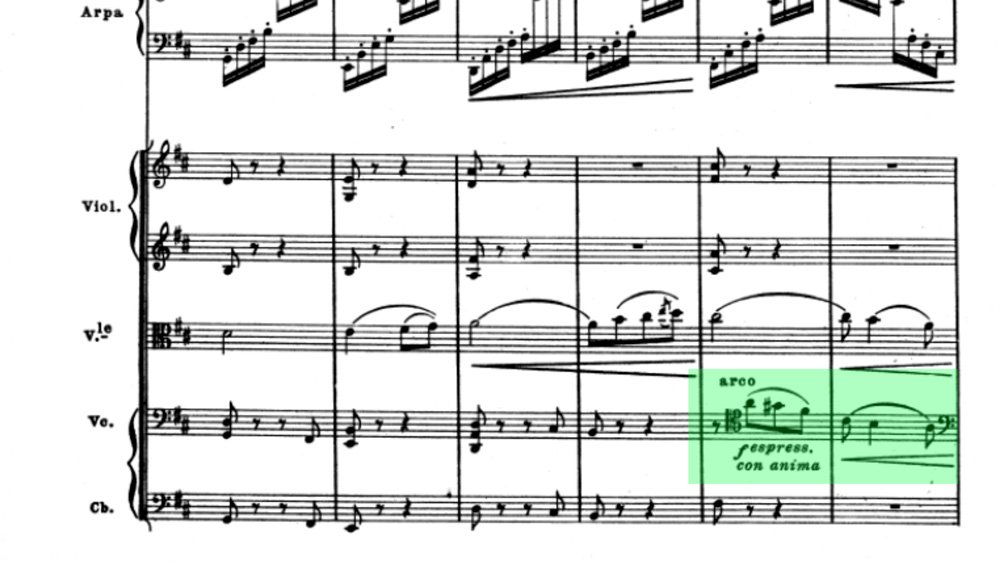

At the Andante calmo the sadness weeps in: the upper woodwinds doubled by the violas carry out the melodic line in a downward progression spanning 7 bars, in a 3+2+2 structure. The accompaniment is offered by a carpet of harp arpeggios colored by the pizzicato of the violins, cellos, and basses

The second part of the phrase moves up, reinforced by a horn and a bassoon. Notice the answer in the cellos, marked espressivo con anima

The phrase closes in diminuendo, calando, which refers to both the dynamic and the tension. This gives way to a fortissimo subito where the melody is taken over by the strings minus the double basses who sustain the harmony.

This way of treating the strings, in unison or octave for long periods, is another stylistic characteristic of Puccini’s writing

6 bars and we are back to pianissimo where the strings are now joined by the flutes, an oboe, and a bassoon. Notice the first 2 bars: the line starts high and moves down, its speed is naturally increased by the use of the triplets, bringing the line back up, while the syncopation over the barline increases the tension

This is the key to the entire following section, using different variations to depict the stirring sentiments of the characters

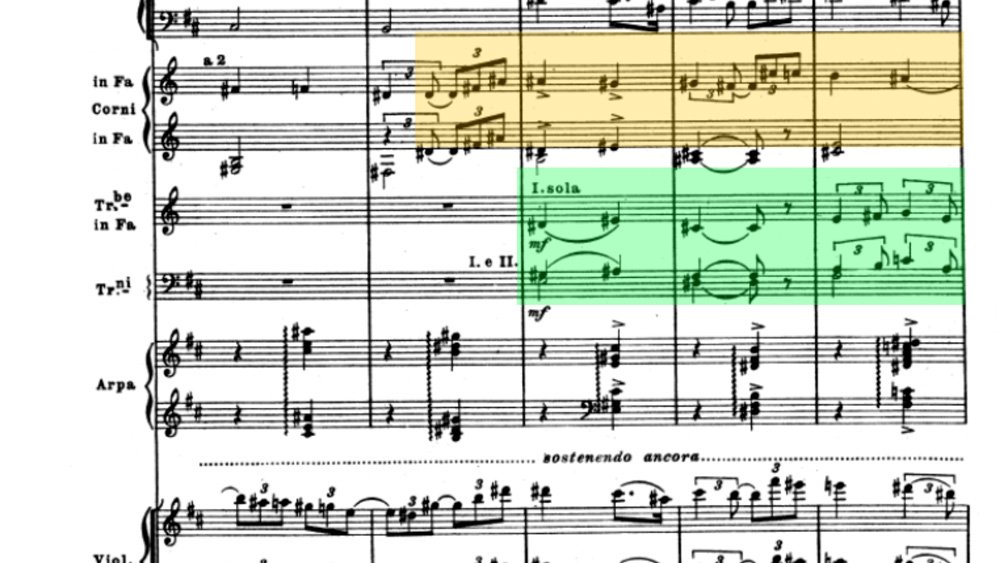

The model turns into an 8-bars model, constantly raising the tension. Notice how the arpeggios of the harp have now moved to the clarinets, while the harp itself has chords on the second beat of each bar. The texture is thickened by the 3 horns playing alternating offbeat eight notes and syncopations. And there’s an extra line – which Puccini wants to be heard as he marks it “sensibile” – played by the English horn, second bassoon, and first horn. nothing, however, can take the attention away from the swirling passionate vortex of the strings

Technical tip

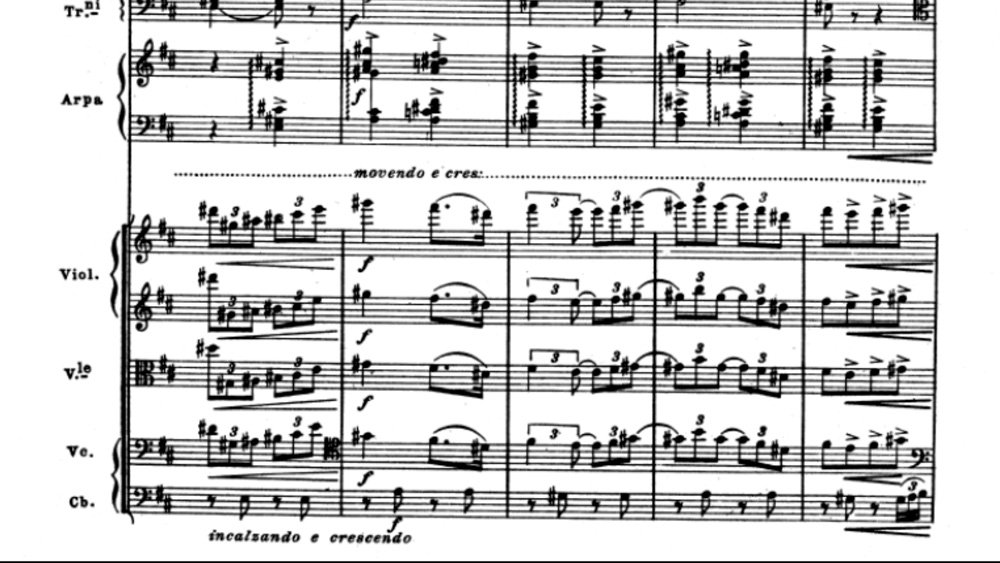

The most difficult aspect conducting-wise is the rubato: in this part alone, the first phrase is marked ‘movendo‘ which means moving; but the following phrase is marked ‘sostenendo‘.

It’s a game of push and pull: to get the most out of it you need to anticipate the orchestra so that they have time to react. However, in order for it to be seamless and not sound forceful, have in mind clearly where you want to go and allow yourself enough room to get there

For a full technical analysis, with a focus on how to conduct the rubato, take a look at this other video

The triplet element returns in this very last section, leading for a moment to one last fortissimo before closing in a quadruple piano. Notice how the motive is passed from a combination of piccolo, clarinet, and harp to the cellos, English horn, clarinet, and horn, moving down to a clarinet and bassoon, and finally to a pizzicato of the double basses

If you want to hear the full duet, I suggest the 1954 recording with Mario Del Monaco and Renata Tebaldi with the Orchestra of Santa Cecilia conducted by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli.

0 Comments