Introduction

Schumann began writing the first ideas for his first Symphony in January 1841, precisely from 23 to 26. It seems that he completed the work entirely by the end of the following month.

On March 31st of the same year, the symphony was premiered under the baton of none other than Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, during a benefit concert for the Gewandhaus Orchestra. The same concert marked the return to the stage of Clara Schumann, who after her marriage to Schumann had had to temporarily put on hold her concert career.

The great success of her return to the stage overshadowed Schumann’s First Symphony, which was only one of the works in the program.

Schumann revised his work several times, so much so that the final version of the work dates back to 1853.

Clara Schumann in 1853

Schumann Symphony n.1 “Spring”: an analysis of the 1st movement

Exposition

Andante un poco maestoso

In case you don’t have it at hand, here’s a quick link to the score.

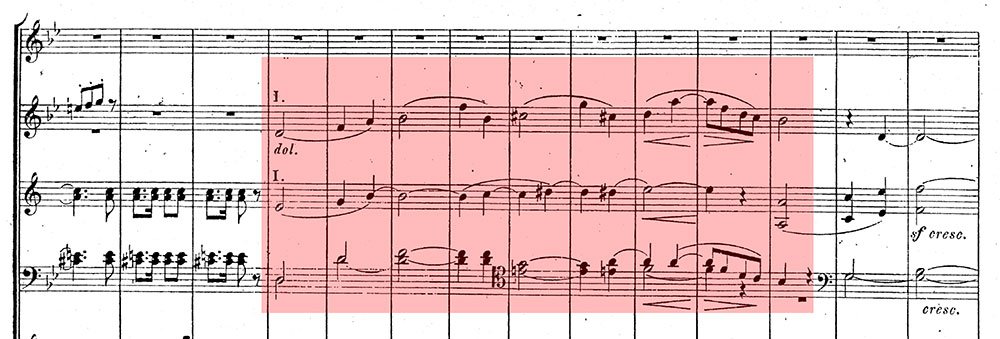

Here’s an interesting fact: the famous opening figure with horns and trumpets was written this way

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

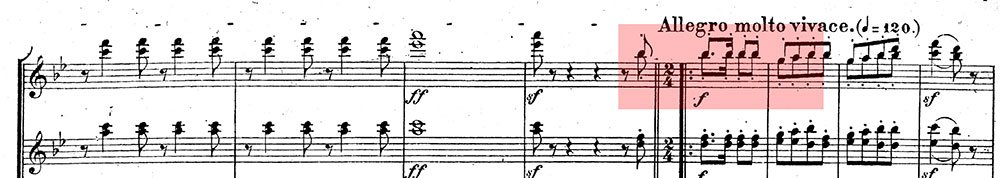

Allegro molto vivace

First theme

There’s a tremendous buildup, the tempo gets faster, the orchestration thickens, and on the F pedal starting on bar 31 we get to the Allegro molto vivace.

The main theme is a contracted version of the opening bars.

The opening phrase is a very well balanced 16 bars phrase, 8 + 8, just as we’ve seen in Haydn Symphony 104. Except: usually, the first 8 bars end on the dominant which resolves on the tonic the following bar. In this case, we land on the dominant with a modulation (so, it is, in fact, already a tonic); and then we start back on the 6th grade of the Bb major scale, ending the phrase back into the home key.

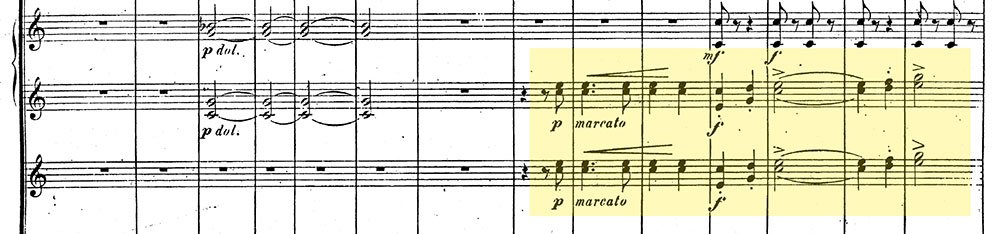

Second theme

The interesting thing here is that this theme seems to be more of a parenthesis: it’s quite intimate, with an atmosphere of a romantic Lied. But beyond that, Schumann does not make any use of it in the development. We will see this theme re-appearing only in the recapitulation

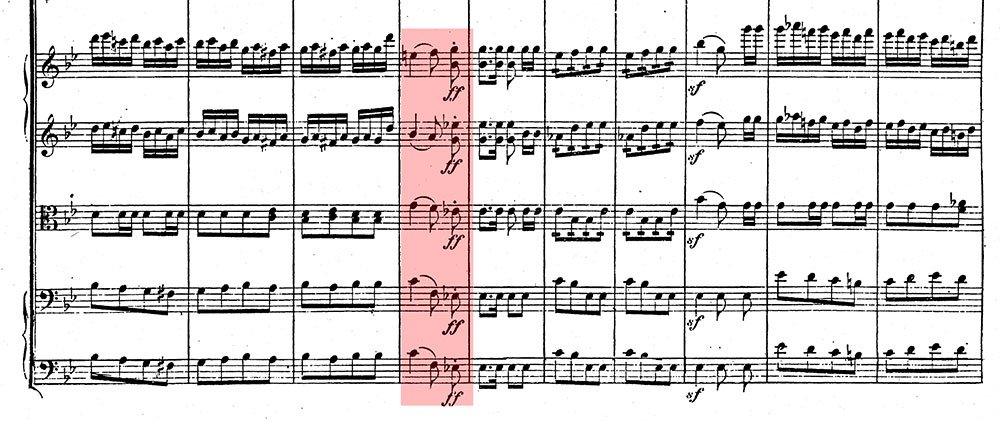

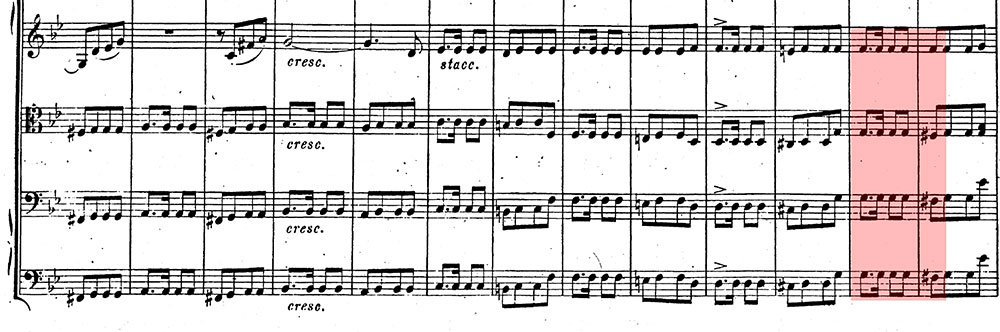

The second theme modulates itself and lands on the dominant key on bar 117. But along the way you can see how Schumann reuses all the elements and transforms them into something else: the 16th of the violas, which are used as a counterpoint at first, turn into a motive in the first and second violins;

the syncopations of the violas are transferred to the woodwinds, and then to the rest of the orchestra, merging the 2 motives on the forte in bar 110.

The now familiar dotted figure comes back in an upward and downward scale and closes the exposition in F major.

Development

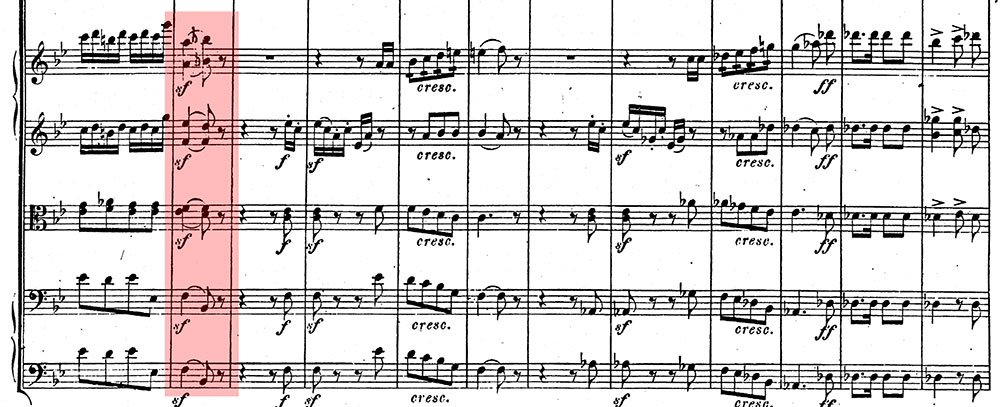

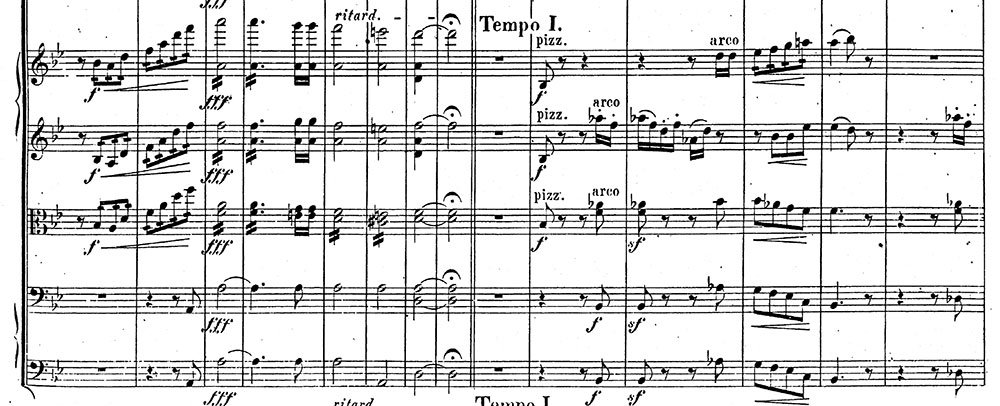

The development is purely classical. It starts with the first theme getting tossed around from section to section.

Everything happens within a model that moves up of a whole step each time. And the melodic counterpoint in the woodwinds on bar 150 and following will be echoed in the coda of the movement

But because the bass line movement of ½ step is part of a progression we’ve heard now for more than 10 bars it does not sound harsh at all. Schumann has gotten our ears used to that ½ step and a dissonance of a minor second perfectly fits into the picture. It’s brilliant.

On bar 178 a larger section begins, moving the material in a progression of fifths from D to G to C to F major on bar 202. And here, the same ideas of the beginning of the development return. So, we have, in fact, a sort of double development: the first one begins on the tonic, the second one on the dominant key

Recapitulation and coda

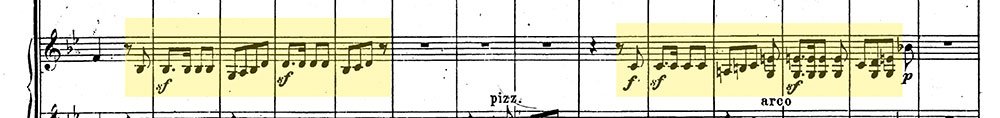

The introduction is, of course, cut short, and we land on the Tempo primo. As per tradition, the recapitulation is somewhat contracted, and we soon land on the Coda at the Animato.

Notice that Schumann also writes Poco a poco stringendo underneath.

We expect a swift ending. But Schumann has another surprise for us: a new theme. In the coda, which was really unheard of. On top of that it’s in a piano dynamic.

In conclusion

Much has been said about Schumann and him not being a good symphony composer. I personally disagree. I believe his symphonies are full of surprises, some of them in that orchestration that is so often looked down on. Schumann is capable of impressive ups and downs and requires a great deal of energy and focus for a conductor. When you do it, brace yourself because at the end, you’ll be happily drained!

0 Comments