Introduction

It was with the opera Euryanthe that Weber, a contemporary of Beethoven, aimed at the close union of arts already advocated by Hoffmann. In Weber’s own words:

Carl Maria von Weber, 1821

“Where in other nations – are the words of Weber himself – everything is sacrificed to momentary sensual joy, Germany intends to create a work of art as a whole, where all the parts come together harmoniously in total beauty”. A concept largely inherited by Wagner.

A concept largely inherited by Wagner.

Weber’s name is linked to his operatic trilogy: Der Freischūtz, Euryanthe and Oberon.

In these three operas, Weber paved the way to the new conception of German opera, from which the Wagnerian musical drama will derive.

We are still in a structure dominated by closed numbers: arias, duets, terzets, choirs, etc.. But the idea is to create a superior unity of “musical scene“, where every aspect, musical, visual, and theatrical come together in anticipation of Wagner’s gesamtkunstwerk, the “universal artwork“.

The libretto – the weak point of the opera and the reason for which it failed – was written by Wilhelmine von Chézy, and taken from a medieval novel entitled “Histoire de Gerart de Nevres et de la belle et vertueuse Euryanthe de Savoie, sa mie“.

Incidentally, the same story inspired Boccaccio for one of the stories of his Decameron and Shakespeare for the play Cymbeline.

The material for the overture comes from the material used throughout the opera. Many of these motives are associated with a specific character or a situation. Again, something that Wagner will pick up and master in his works.

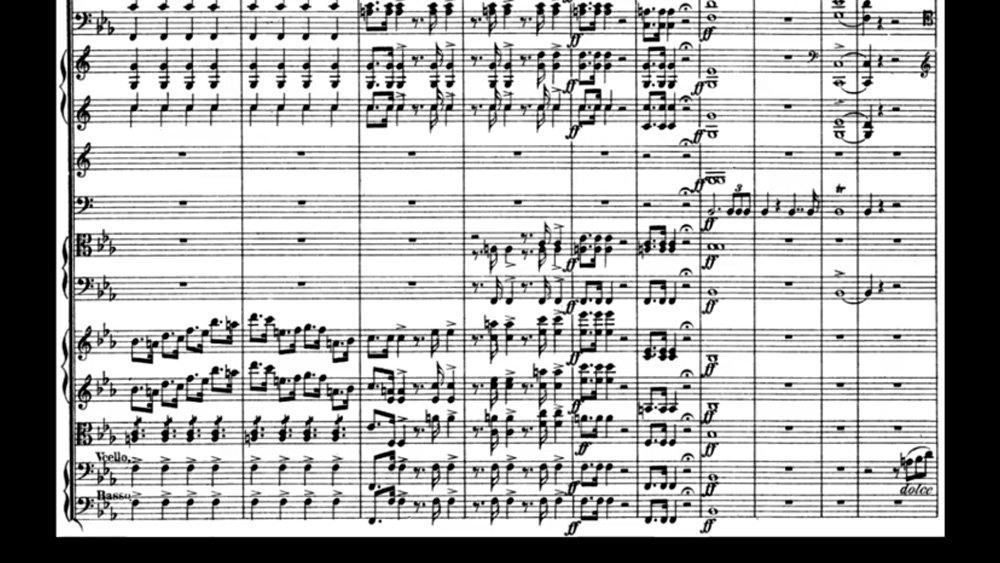

C.M. von Weber – Euryanthe, Overture

Should you need a score you can find one here.

First theme

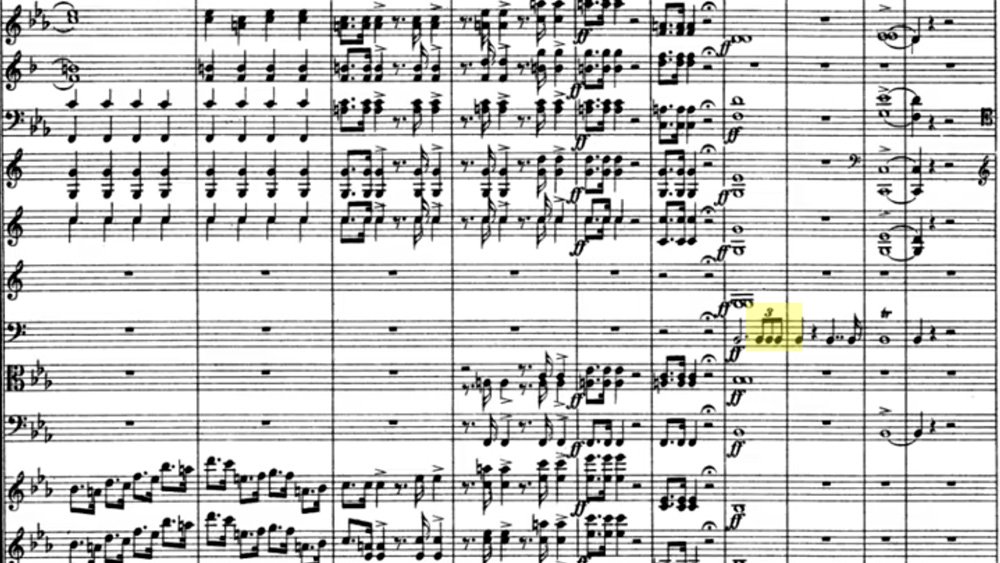

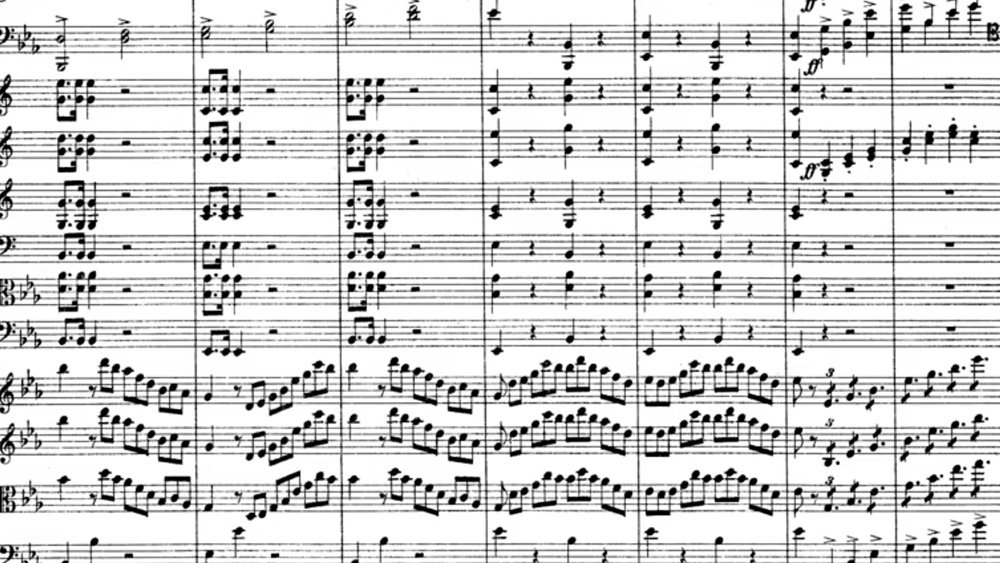

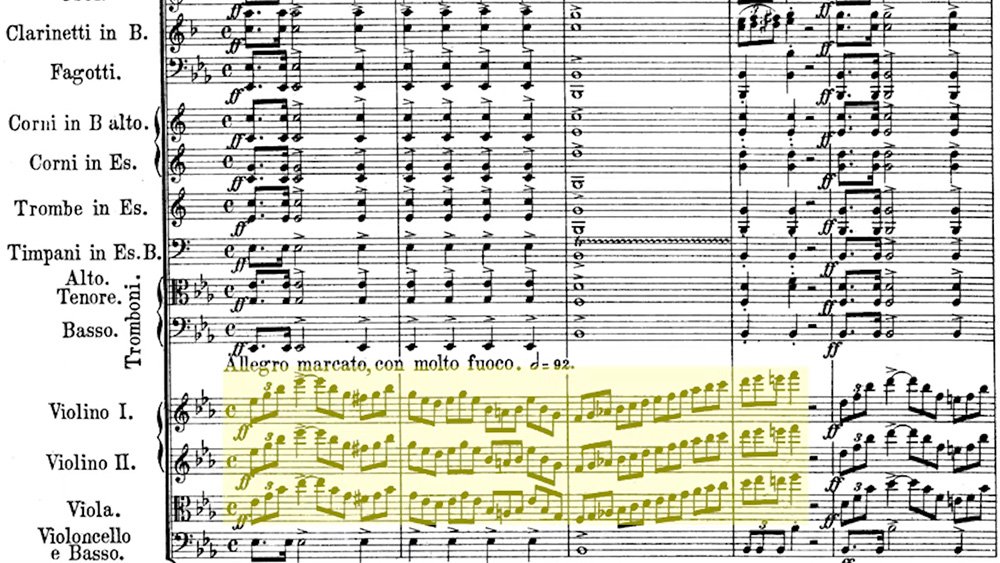

There’s an incredible outburst of energy that opens this overture: the full orchestra explodes in a fiery Eb major. The tempo indication bears the marking “con fuoco“, with fire, which the violins and viola exploit with their triplets, rising up, cascading down and then up again

The strings join in and take us to the initial fervor. However, it’s not a simple repetition. The triplets figures bounce between the violins and the low strings while the dotted figure we’ve heard from the woodwinds is reworked into the fabric of the music until it takes over, in the strings, and leads back once more to the initial triplet figures

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Second theme

The second theme is introduced by a powerful statement in fortissimo. The orchestra leaves the timpani alone, giving us, once again, the triplet and the dotted rhythm element, fading out to prepare the entrance of the cellos. Notice the chord in the woodwinds and brass.

The second theme comes, as expected, in a different character. A typically romantic line, the feminine opposed to the masculine of the first theme, as we’ve seen many times in the past episodes within the construct of the sonata form.

Notice the presence of the dotted rhythm as a connecting element to the previous section.

It is, in fact, this element that prepares us to the next musical episode, which begins, guess what, with an energetic gesture in triplets

We enter the coda of our exposition. The transition is all based on the dotted figure and the long chords we heard at the introduction of the second theme. Fading out, the chords are stretched while the dotted figure moves from the violins to the violas. It’s a moment of great anticipation, dying out in complete silence

Development

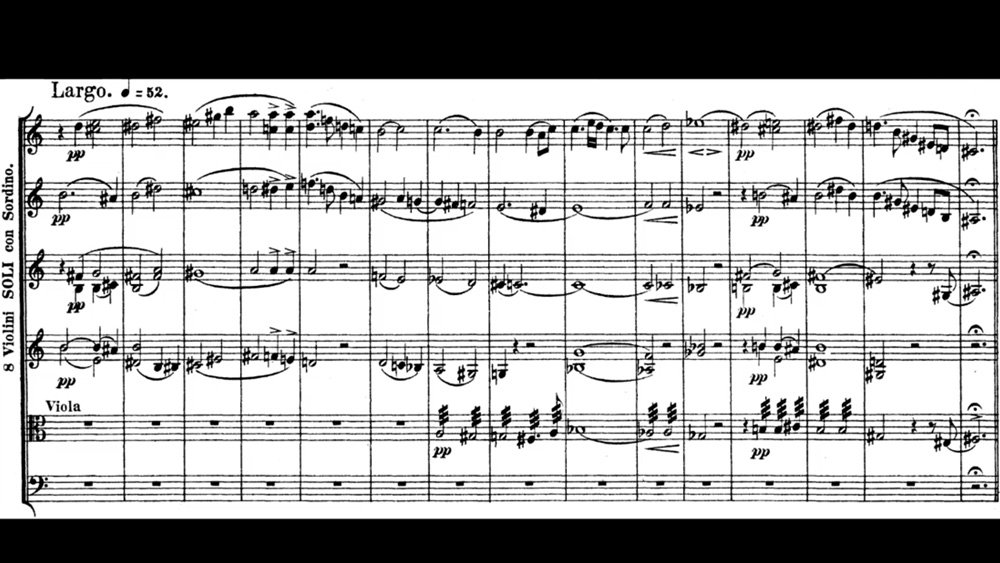

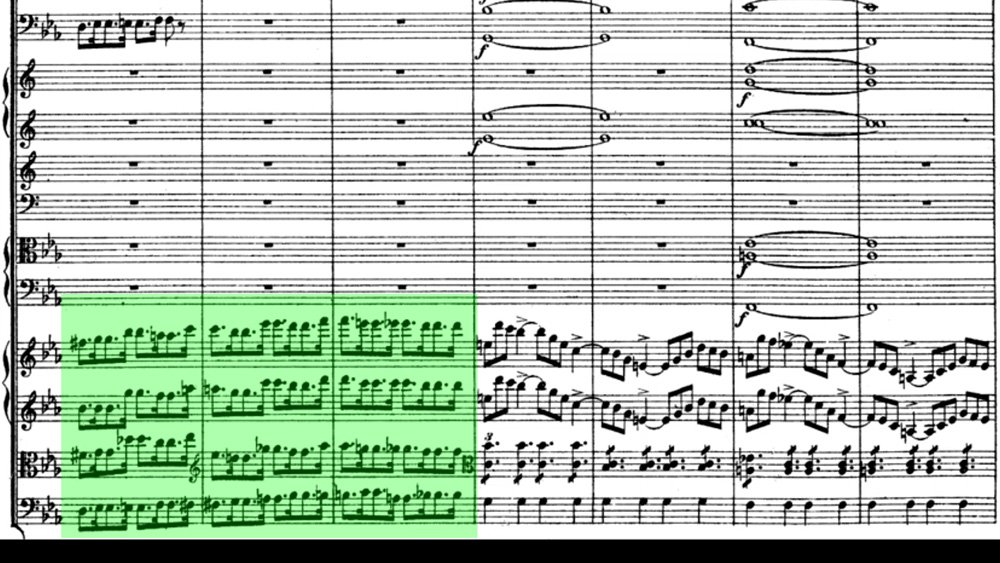

Now comes the surprise. What would you expect here? The development obviously, a rework of the musical material, reaching a powerful climax and leading back to the exposition. We may get all that still, but Weber starts out with an unusual Largo. 8 solo violins, with mute, nobody else in what sounds like a tender prayer

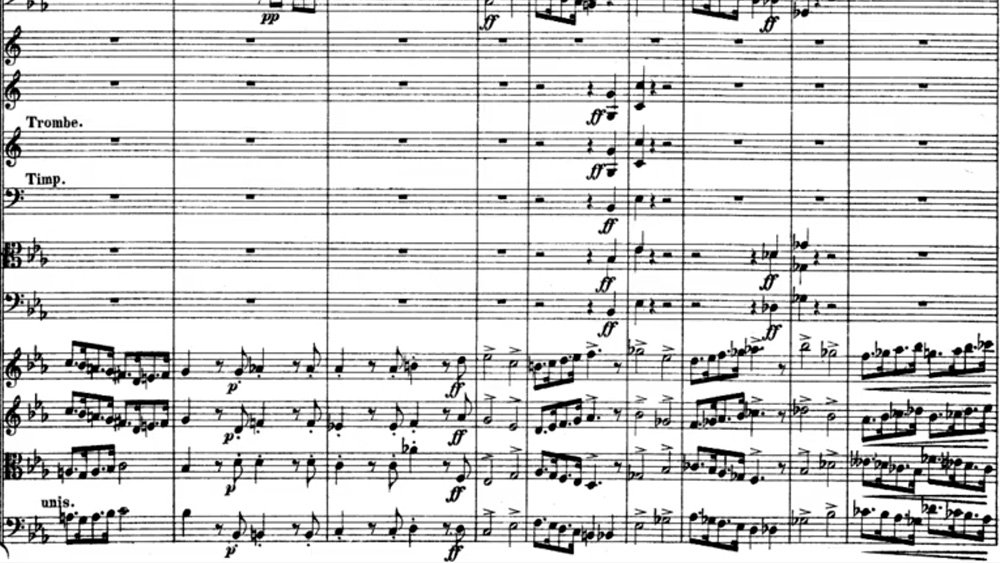

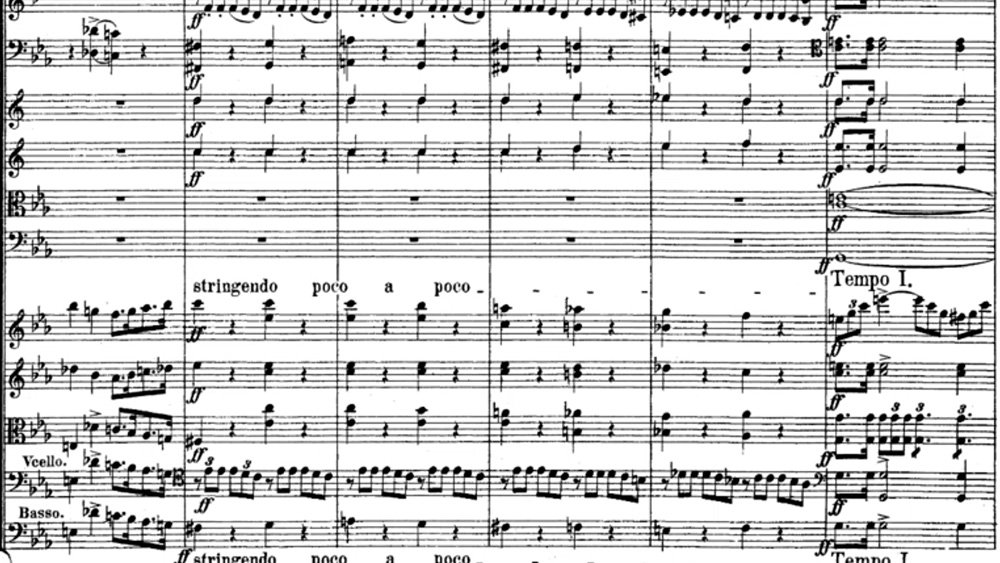

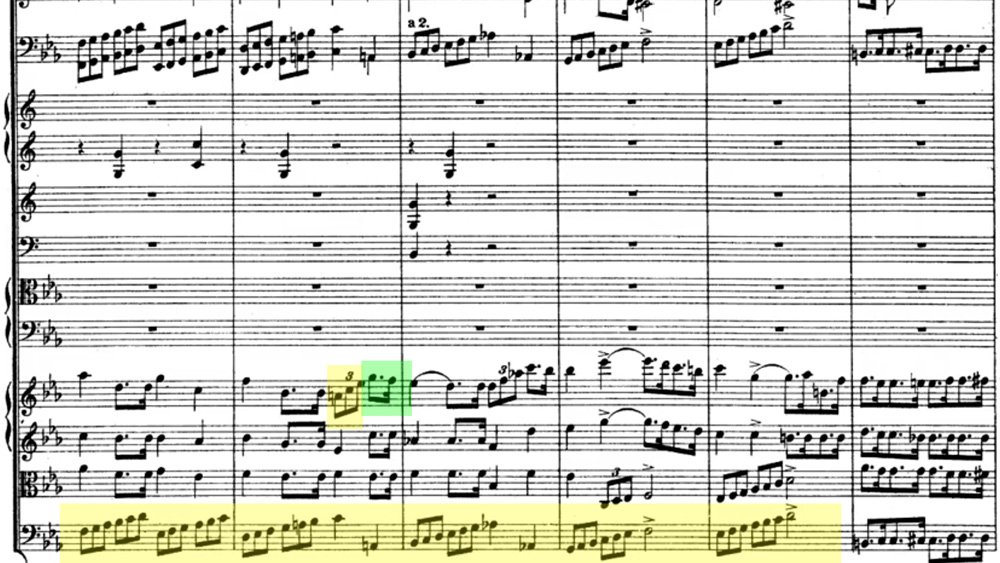

A Tempo I throws us back in the battlefield with a fugato: cellos and basses tailed by the second violins and violas, and then the basses with the first violins in counterpoint. Naturally, the triplets and the dotted rhythm rule

We are, as expected now, in the full development section: you can see bits and pieces of the musical material being tossed around, bouncing from one section to another, changed in key, in their original profile but still very much recognizable.

The material of the fugato for instance – which comes straight from rehearsal letter A at the beginning of the overture – is flipped up and down, assuming different forms at each turn

The triplets are used to build an accelerando which aims to trick us into a faux reprise, a false recapitulation. We land on a theme that’s very similar to the first theme but it’s in the “wrong” key of C major

Another anxious moment and a full orchestra Bb chord on the dotted rhythm, followed by a rising scale in, of course, triplets, leads us to the real recapitulation. Shortened in some sections, more compact, the recapitulation presents a few changes. The most notable one being the second theme, now coming in a full heroic fortissimo while the coda mixes up both triplets and the dotted cell with great energy.

0 Comments