Introduction

The Coriolan Ouverture could be defined as a miniature symphonic poem, in that it has an inherent descriptive character (much like the Egmont Ouverture). Both of them, as a matter of fact, are overtures to a theatrical drama: Collin’s Coriolan, and Goethe’s Egmont.

Beethoven’s idea is clearly to feature all the characteristics of the drama in a single, compact symphonic piece. Collin’s drama is rich in contrasting tensions, which offers Beethoven a perfect opportunity to showcase his own personality through music. Beethoven also effectively started a genre that will see much success in the first half of the 18th century: up until then, an overture was used to open an opera; with Beethoven, we see the ouverture as a standalone concert piece. This idea will be followed by many composers, like Mendelssohn, Berlioz, and Brahms. Not only: this idea will also be the germ for another form, the symphonic poem that from Liszt onward was destined to much success. The very same 1st movement of Mahler’s second symphony, in fact, was born as the symphonic poem “Totenfeier“.

The drama of Coriolan turns around the tragedy of the roman hero who defeated the Volsci but was then exiled from Rome; in order to take revenge against Rome, he forms an alliance with the Volsci themselves. When he’s about to attack Rome, his wife and his mother enter his tent and manage to convince him to desist. Depending on the version of the story (Collin, Shakespeare, Plutarch) Coriolan either kills himself or is killed by the Volsci.

Coriolan painted by Nicolas Poussin, 1652-1653

Musée Nicolas-Poussin, Les Andelys

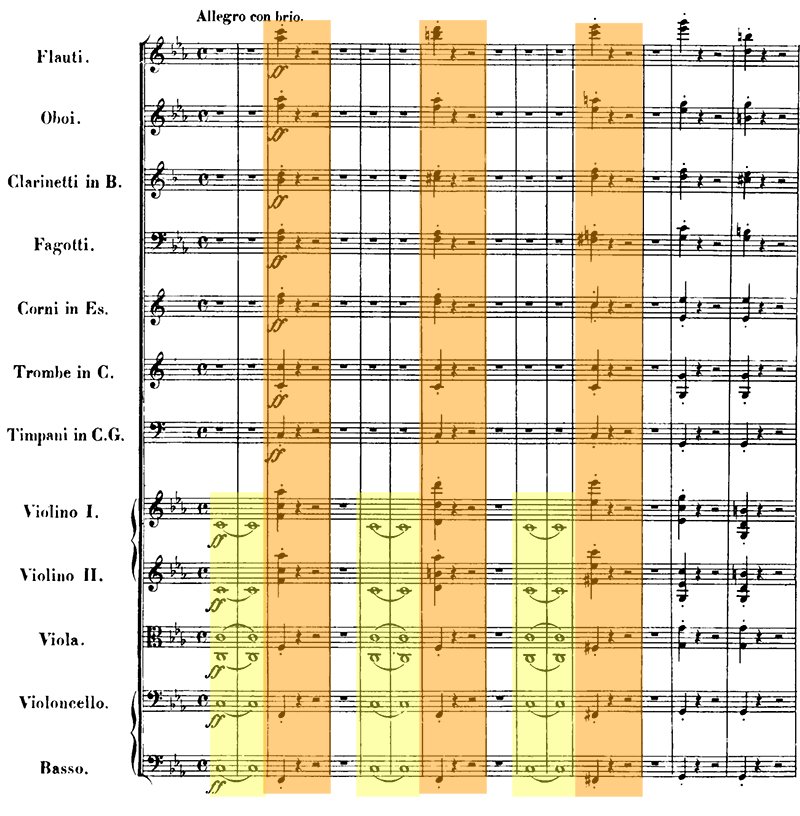

Beethoven: Coriolan autograph

Courtesy of the Beethoven digital archives at the Beethoven-Haus

Beethoven’s Coriolan Ouverture: analysis

Exposition

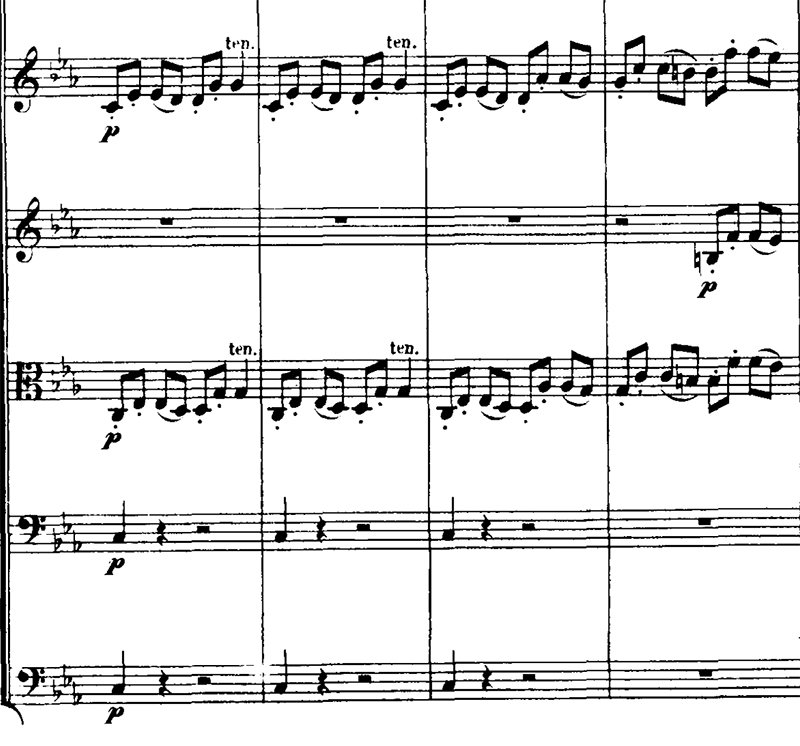

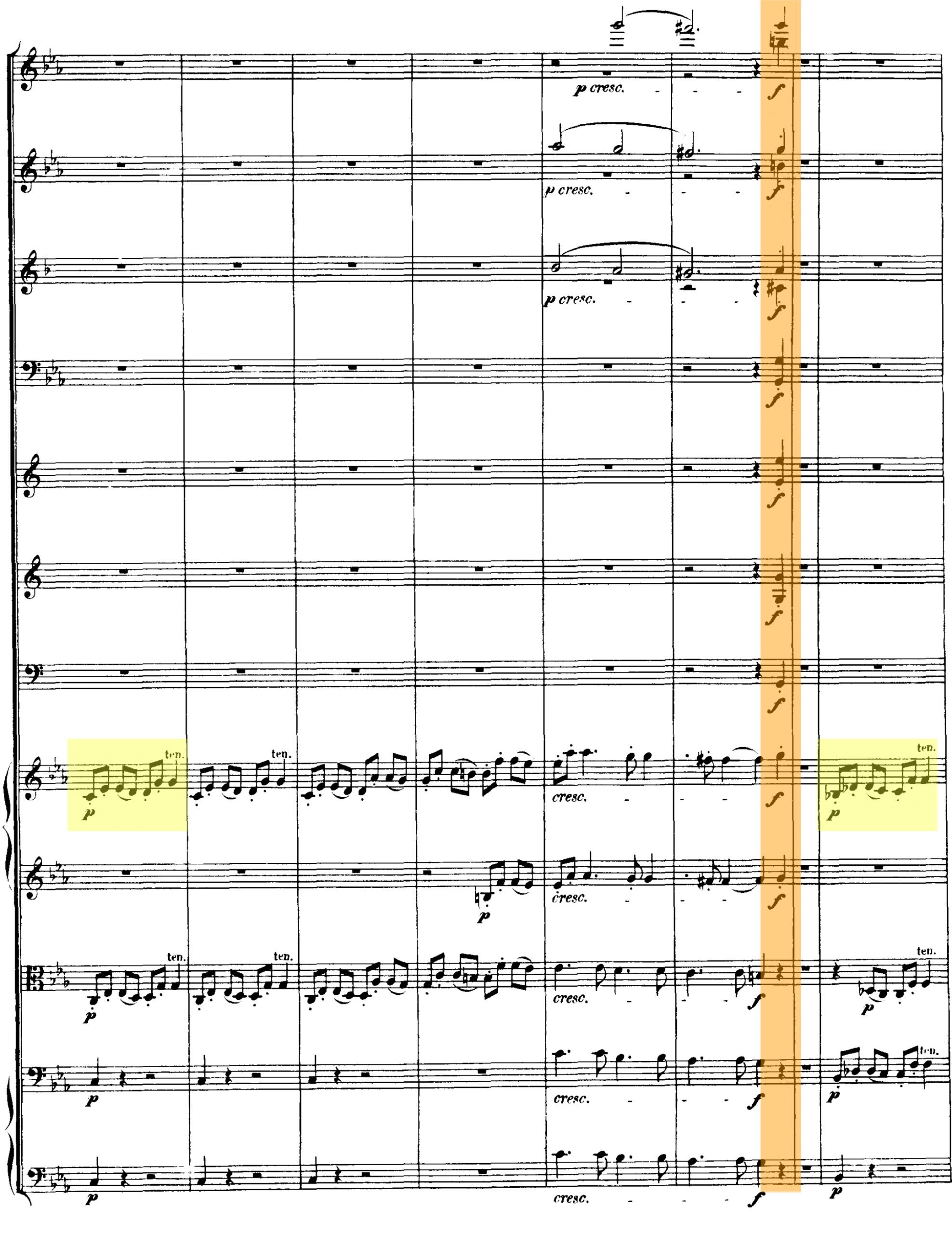

The dualism of the character, fighting his own internal contrasts of love and revenge for Rome, is the starting point for Beethoven. The Coriolan Ouverture begins with a dramatic gesture of a long note in the strings, followed by full orchestral chords. This incipit is repeated 3 times: 3 times in which Beethoven changes only the chord, adding more and more drama to it, amplified by the use of the rests.

Technical tip

Avoid using both hands all the time: swap between one and the other thinking about the weight you want to impress on sound. The last 2 chords can also be conducted sideways, with a sharp, quick rebound of your right hand, leaving the left in position for the piano at bar 15.

After a cadenza of 2 chords, we would expect another fortissimo chord in the home key. But Beethoven doesn’t fulfill this expectation, introducing a sudden pianissimo. It’s typical of Beethoven to change the dynamics to keep the tension. Notice how Beethoven does not use any melodic element in the first 14 bars but relies exclusively on harmony and rhythm. In full contrast, when the first theme comes in on bar 15 there is no harmony: only a C on the downbeat of the first 3 bars. Sure, one could argue that the harmony is somewhat implicit, something we can deduct with our ears accustomed to disentangle the intricacies of Bach, a composer that was completely unknown to the audience at that time. Regardless, Beethoven does not make it obvious, leaving the violins and violas completely unaccompanied.

Everything is in piano, no change in dynamics for 4 bars where only the melody reigns. The absence of dynamics makes the contrast with what came before and with what is about to come even more extreme. The menacing chord from the opening comes back once

then the conversation is passed again to the strings, playing the same theme a whole step lower.

Technical tip

If you want to emphasize the last chord of bar 20, retake the stroke with a short and clean gesture, stopping the rebound.

Beethoven uses the same musical cells to continue, arriving at a fortissimo which holds another Beethovenian fingerprint: those dotted quarter notes in the winds and lower strings are an element that we will find over and over again, one remarkable example being his ninth symphony.

Oops...

This content is available for free with all memberships.

Already a member? Login here.

Not a member yet? Subscribe today and get access to more than 80 videos, scores analysis, technical episodes, and exercises.

Second theme

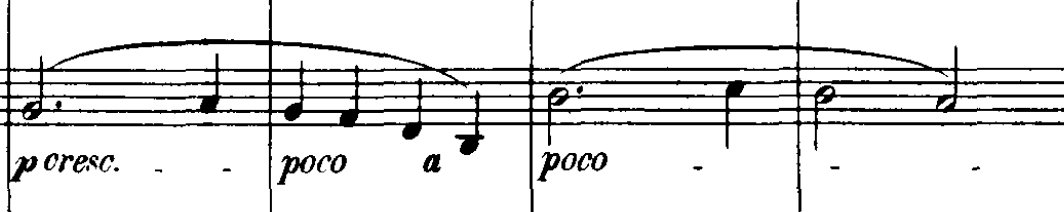

We land on a sweet and delicate second theme, again in contrast with everything else: a typical example of an antithesis between a first theme, masculine and aggressive, and second theme, feminine, and cantabile. We can almost see Coriolan’s wife and mother imploring him to give up on his revenge.

The lovely Eb major is suddenly interrupted by a fortissimo, like Coriolan vehemently making his argument.

The theme comes back but it’s now in a melancholic F minor. We are interrupted again and taken to G minor. And then, at bar 77, it’s all rhythm: the anxiety of Coriolan palpitates through the strings and the bassoons, helped every 2 bars by the flute and oboe.

Technical tip

Keep an eye on your pulse: it’s very easy to speed up here, so control your rebound.

Development

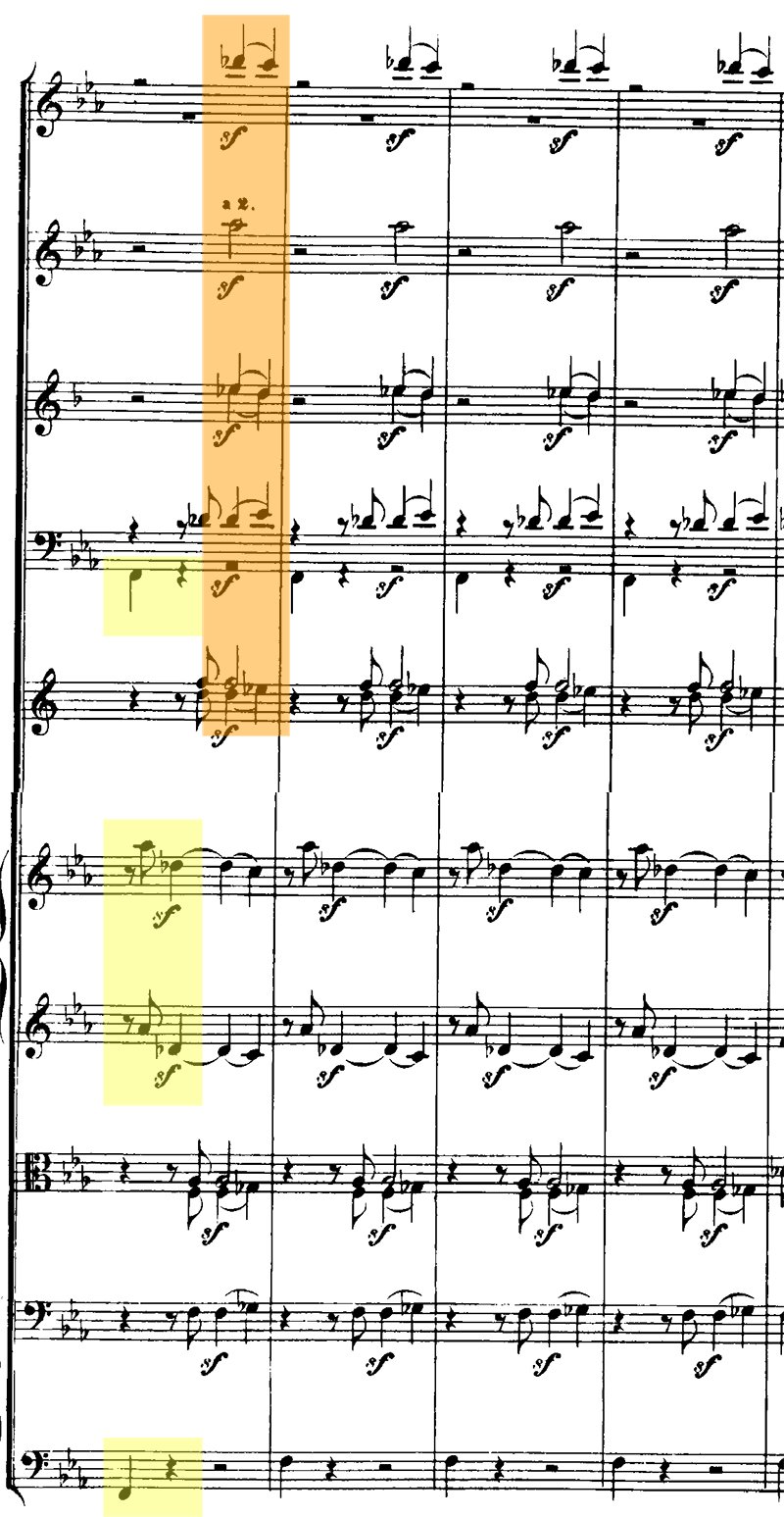

The development uses, naturally, the material from the exposition, reworked in different ways but keeping mainly the rhythmical aspects of it.

Technical tip

At bar 118 and following swap hands between strings and woodwinds, and keep your gestures to a minimum.

In this disrupted dripping of musical elements notice how the cellos, with their long notes at bar 133, add tension and lyricism at the same time. Between bar 136 and bar 140 make sure there is no crescendo. And 140 is only forte, the fortissimo comes at 148. Again, contrast.

Notice also the held oboes in crescendo (doubled by the bassoon) at bar 144, a composing “trick” Beethoven learned from Mozart.

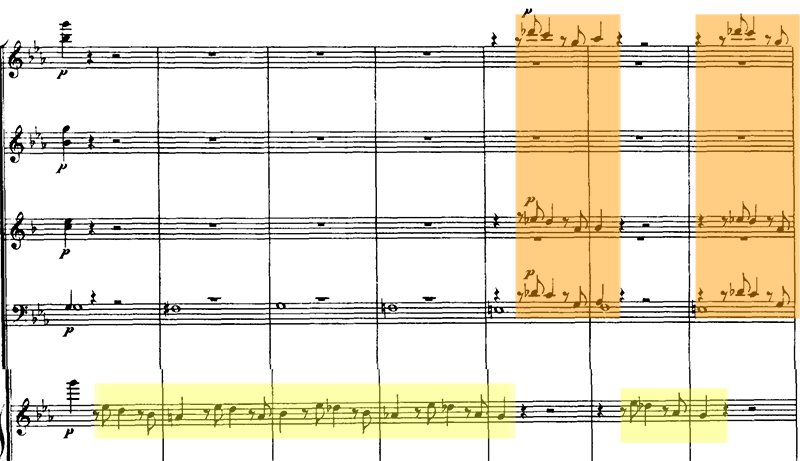

Recapitulation

The recapitulation, which arrives at bar 152 in a different key from the opening, is extraordinarily compact in comparison to the exposition: everything is fragmented and the repeated, obsessive elements take us directly to the second theme. While this theme in the exposition arrives after 52 bars, in the recap arrives after only 26 bars. The drama is concentrated, deprived of all ornaments, and focused exclusively on its very essence. Just listen to the gripping power of those horns in unison at bar 168 and the timpani and trumpets at 171.

Technical tip

Once again, at bar 220 you can use one hand for the violins, 2nd bassoon and basses, and the other for the woodwinds and horns, and violas and cellos. It will add weight to the sforzandi and will show the dialogue between sections.

The conversation moves on, playing on the various motives until it gets stopped at bar 240. Silence is used as a dramatic weapon once again, leading us into the coda.

Coda

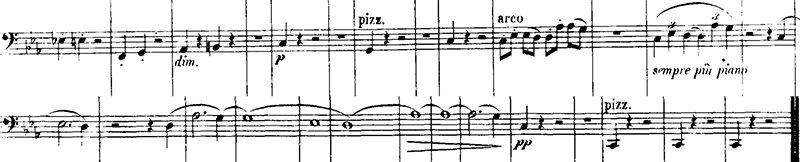

The coda opens with the imploring second theme leading into a dramatic part where Coriolan seems to have the full weight of the world on his shoulders, unable to decide, filled by the doubting chords of bars 264-269.

Eventually, the music folds on itself, resolving on the opening gestures. The music breaks, dissolving itself, and the ghost of that first motive comes back completely dismantled, moving from eight notes to quarter notes triplets, from dotted half notes to whole notes while our hero dies on the pizzicatos of the strings.

This idea was not new to Beethoven: he had already experimented with it, for instance in the finale of the 2nd movement of his 3rd symphony (which is by the way in the same key). Might be a coincidence, but the Marcia funebre from the Eroica is also centered on the death of a hero. And, incidentally, so is Mahler’s 1st movement of the 2nd symphony, which also ends with pizzicatos on a C. They all share the same key of C minor.

In conclusion

The driving rhythms and the raging power contrasting with the sweetness of the theme is what I enjoy the most when conducting this piece.

0 Comments